More than half of anchovies and all of the seabirds that feed on them were found to have microplastic particles in their digestive tracts, according to a study by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

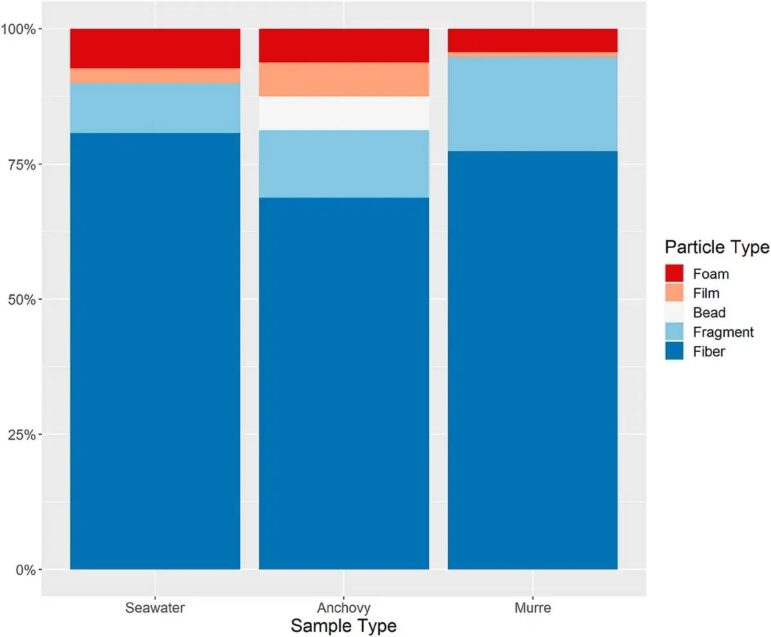

The researchers tested 24 anchovy and 19 common murres for microplastic particles and found particles of at least 5 millimeters in 58 percent of the fish and all of the birds.

The researchers also analyzed seawater samples from Santa Cruz and Moss Landing, finding a microplastic concentration of about 2 microparticles per 1,000 liters.

Roughly one quarter of the particles found in the murres also had the potential for estrogenic activity, according to the researchers, meaning they could disrupt the birds’ hormone production.

The study was accepted for publication earlier this month in the journal “Environmental Pollution.” “These tiny plastic particles are leaching substances that have the potential for hormonal disruption that can have cascading effects on reproductive and immune functions,” said senior author Myra Finkelstein, an adjunct professor of environmental toxicology at UCSC.

According to the researchers, the presence of microplastics in coastal waters has a cascading effect on food chains and ecosystems, as fish can accumulate them by filtering plankton and other microorganisms from the seawater.

Those particles are then transferred to birds and other larger animals that consume small fish, including humans.

Birds are also often at risk of consuming even larger pieces of plastic, called macroplastics.

“One of the main problems with macroplastics is that they’re taking the place of food,” Finkelstein said. “With microplastics, a major concern is the toxic compounds that may be leaching out of it.”

The researchers plan to conduct further studies with the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance of how the microplastics may be affecting fish and birds physiologically.

“We believe this is the first time this type of estrogen-based assessment is being conducted for this type of widespread marine pollution,” said Christopher Tubbs, the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s associate director of reproductive sciences.