At the beginning of the solo play “Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski,” we learn the basic facts: that Karski was born in Poland in 1914, that he was “the man who told of the annihilation of the Jewish people while there was still time to stop it” and that he was a professor at Georgetown University from 1952 to 1992.

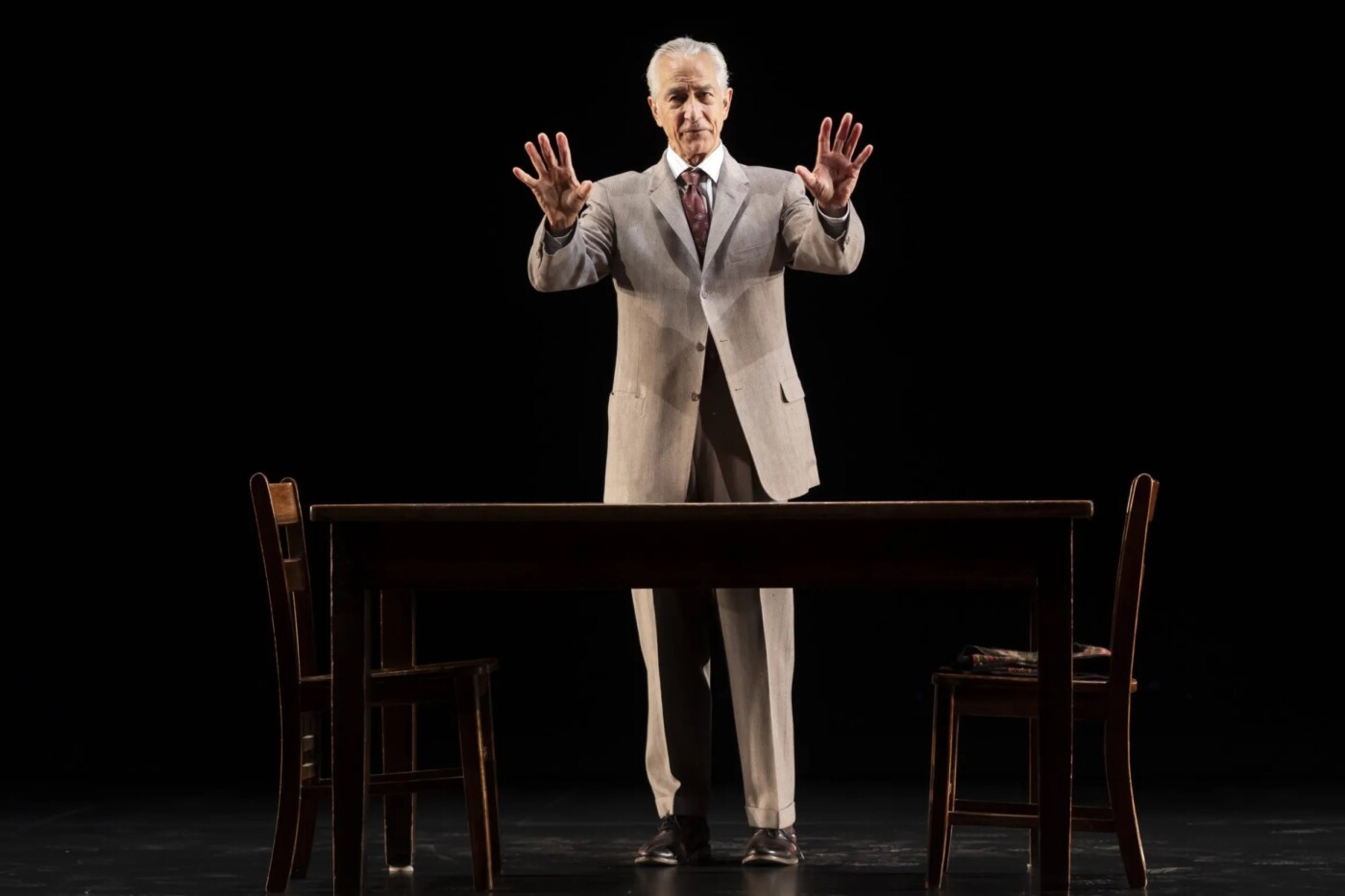

From that point on, Emmy Award-winning David Strathairn (a San Francisco native who played Edward R. Murrow in the movie “Good Night, and Good Luck” and appeared in many other films including “Nomadland”) portrays the humble “messenger of the Jewish people to the world.”

In the show, onstage at Berkeley Repertory Theatre from Dec. 2-18, Strathairn also plays other historical characters from the World War II era, including Hermann Goering, and, significantly, Szmul Zygielbojm, a Polish-Jewish socialist politician in exile in London.

Strathairn turned out to be a more convincing Karski than playwrights Derek Goldman (who directs the show) and Clark Young anticipated.

“People felt very emotional when (Strathairn) was still holding the script,” Goldman said in a recent Zoom chat. “He was capturing the spirit and the physical reality of him.”

The play, which had an Off-Broadway run and other performances worldwide, is produced by the Laboratory for Global Performance and Politics. Both playwrights, professors of performance studies at Georgetown, plan to be here throughout the short run.

Goldman and Young joined forces with Strathairn from the outset of the project in 2014. The threesome formed a close collaboration. Young had been Goldman’s student at Georgetown and Goldman, who previously worked with Strathairn, never considered anyone other than the powerfully low-key actor for the role of the man whom Georgetown students and colleagues still remember reverently.

After the Nazis captured Poland, Karski, who was a diplomat, joined the Polish underground. He was approached by leaders of the Jewish underground to become a messenger to warn Allies of the planned liquidation of the Jewish population.

“Poland will emerge again,” they tell him, “but the Polish Jews will no longer exist.”

After he saw the Warsaw ghetto and a concentration camp, Karski was all in. He risked his life, spreading the word about the Holocaust from Warsaw to Berlin to Brussels to occupied Paris to London (in a futile attempt to talk to Winston Churchill, who, in 1946, said he’d had no idea of the scale of the massacres).

“I report what I see,” Karski said, “I am a camera.”

In a scene in which Karski eventually gets a meeting with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the president seems more interested in finding out whether the Germans had taken horses from agricultural Poland than in getting information about the plight of the Jews.

For 35 years, Karski never talked about his experiences, never even mentioned to his students he’d been in the war. “I was forgotten, and I wanted to be forgotten,” he says in the play. And he was, until filmmaker Claude Lanzmann insisted on interviewing him for “Shoah.”

Goldman, Young and Strathairn had a wealth of historical material to consult in shaping the 90-minute play. While Goldman and Young joined the Georgetown faculty after Karski, who died in 2000, retired, other professors and Karski’s former students provided a wealth of personal information.

There was also Lanzmann’s interview; Georgetown library archives; the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Karski’s own memoir from 1944, “Story of a Secret State”; E. Thomas Wood’s 1994 biography “Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust”; oral histories and more.

“Even people who happened to meet him on the street feel compelled to talk about what a unique person he was,” says Young. “He’s always been a lodestar or mentor.”

Goldman notes that the collaboration among the creators across three generations —Strathairn is in his 70s; Young is the youngest — revealed somewhat different perspectives on the particular history that the play illuminates, “how each of us has inherited and lived it.”

The play, he says, “is ultimately, for us, about the responsibility of young people to take action, (to figure out) what they’re going to do in the world.”

Karski’s own ethos was that every individual has the infinite capacity to do good or evil.

Of the emotionally loaded nature of the material, Goldman says, “I knew from the beginning that we could trust the words, the narrative grace of David as Karski, and the audience to find their way to these memories and this history in their own way. … For many this piece feels somewhat like a balm, a palliative … (but) not because it’s easy. It’s detailed and specific …very simple and elemental in a way that I think returns us to the kind of ancient functions of theater, which are of course about bearing witness to a story. It has very old bones in its approach to theater.”

The playwrights made sure to include scenes with Zygielbojm, who ultimately committed suicide in protest of Allied inaction. His suicide note is included in the play, says Young, making sure the presence of Jewish resistance is felt: “That dramatization to me is about the anti-Semitism in Poland, underground communities, priorities within Allied and European governments in exile,” he says. It addresses the question of why Karski, a Catholic, has audience with the president, and Zygielbojm doesn’t.

When work on “Remember This” began, Barack Obama was president.

“Resonances of the material have shifted in time,” muses Goldman, “and have only gotten exponentially more urgent: the war in Ukraine, the rise in anti-Semitism … so many echoes. A lot of our process was about distilling to the elemental core what makes Karski’s story so sort of timeless and present and urgent.”

In an email, Strathairn adds, “The most rewarding and encouraging thing about this piece is how every audience has responded emotionally and intellectually to the relevance and potential application of Karski’s ‘lesson.’ Especially students and young people.” He sees “Remember This” as, above all, a current events play.

“Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski” runs Dec. 2-18 at Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s Peet’s Theatre, 2025 Addison St., Berkeley. Tickets are $24-$124; call 510-647-2949 or visit berkeleyrep.org.