In music journalist Danyel Smith’s 2016 ESPN essay on Whitney Houston singing the national anthem at Super Bowl XXV in 1991, she implores readers to recognize the moment: “You have to understand. You have to remember.” Houston was undeniably accomplished by then, but had not yet created the cultural behemoths of the ‘90s (“The Bodyguard,” “Waiting to Exhale”) that laid the foundation of her enduring stardom. She was 27 years old, and her very presence as a Black woman at the biggest sporting event of the year was history-making.

It was also couched within the heady stew of political and cultural tensions surrounding the Gulf War, national surveillance and the racism lodged deep in America’s national identity. Before you see Houston through Smith’s words, you see the world she was navigating, that she was “proof of life” for Black girls growing up in the 1980s who yearned to see themselves honored in such a public way.

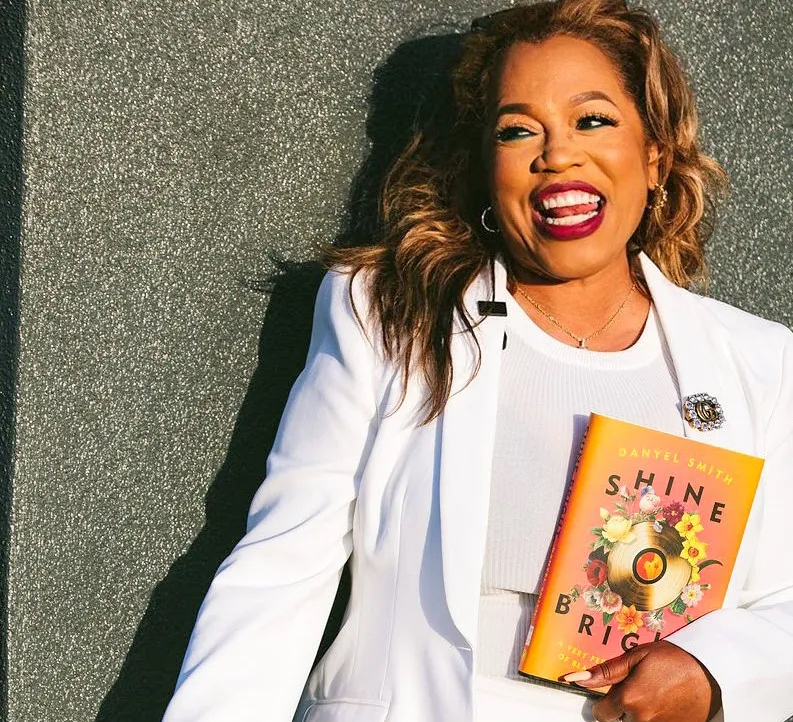

Consider this bit of musical archeology an appetizer to the many courses Smith serves in her blended memoir, “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop, (Penguin Random House, 320 pages, $28), released in April. This context, this relentless commitment to getting the full story, has made Smith one of the greatest music and culture writers of her generation. She’s interviewed everyone (she will double down, everyone), with a byline that swam from SF Weekly to Billboard to Rolling Stone to Vibe, where she was editor-in-chief, to The New York Times. She’s written two novels and now hosts her own podcast “Black Girl Songbook” through “The Ringer” and Spotify. In 2022, she gives readers their own backstage pass to her life and career, finally letting herself become the story.

In a Zoom interview, she says that this book took a while to take shape, but had been forming inside her for years.

“I knew that I was going to write about the women that meant the most to me, professionally and personally—the music that meant the most to myself and my sister. I knew I was going to include the Black woman artists who have meant the most to my mother and her sister, and their friends; the music that meant the most to my grandmother and her sister and their friends.”

American music journalism has holes. Or rather, a narrow lens. We love artists for their inhumanity—how their stardom feels innate. We see them, as we see most success stories, as individuals. In “Shine Bright,” Smith pulls away from the spotlights cast on Houston, Aretha Franklin, The Dixie Cups, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, Gladys Knight, Donna Summer and others to see how they moved through the shadows, and how these shadows continue to obscure their talent, their tribulations, their props. As Smith puts it, “The broad strokes are there. But the detail and the context [are] often sorely lacking.”

We know many of these women for their biggest hits, for their awards and their diva status. But, as Smith insists, to think that these tenets of American music “just pop out of the big, Black woman pop stars, that’s just not true. They did not just become stars. It doesn’t happen like that. So when I’m talking about myself, and my journey in this music world as I say in the book…just to say somebody’s born is reductive. It’s reductive to say that somebody became the first Black woman editor in chief of Vibe —‘became’ is a hell of a word.”

The book’s three parts cover the lives and careers of over a dozen prominent Black women musicians, with many more woven in. To wade through this book is to see that Smith’s story, and the women she features, began well before she was born—misogyny, racism and capitalism apply to both sides of the interview process. First comes Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved woman stolen from West Africa who survived the Middle Passage and became the first published African American poet back in 1773—“a victim who was not allowed to be a victim.” As “Shine Bright” unfurls, it becomes clear that none of these women were allowed to be victims either.

“There were so many commonalities in their lives, story after story. I’m researching, I’m reporting and say ‘Oh, not the bad boyfriend again, oh not the manager that steals all the money. Please tell me we’re not doing this again’—but we’re doing it again. It does not change for Black women, that when you are ambitious, it is a battle.”

These women were not only pop artists. They were opera singers (Leontyne Price), Broadway performers (Stephanie Mills), tastemakers, writers, producers, arrangers. As she writes, “Black music has always had to fight for the credit it deserves for the massive impact it’s had on American culture…the politics of caste overlaid and overlay the democracy of creation.” And because, for many Black artists, their creations come from the lives they lived, their humanity gets overlaid as well.

Rather than dedicate a separate section to herself, Smith’s story emerges between the moments of these lauded women in parallel, much like how an album splices songs with spoken anecdotes. A childhood with her mother’s abusive boyfriend mirrors how the industry divorced Gladys Knight from her extensive musical contributions. A cover story interview with Whitney Houston as her strained marriage became tabloid spectacle becomes a conversation about Smith’s own divorce from her first husband. Not all beats line up so neatly, but most draw chronological symmetry.

Smith grew up in Oakland, in a family who sold records and dealt in music; she then went to Los Angeles, and came back to Oakland for her first years of adulthood. She was accepted to and then dropped out of University of California, Berkeley. Her first paid article was a review of a Natalie Cole show circa 1989, 10 cents a word. From there, she clawed her way into the San Francisco Bay Guardian, then an editor position at SF Weekly, then in New York City as R&B editor of Billboard before working up to being the first Black woman editor-in-chief of Vibe.

But even as she divulges so much, how her pseudo-stepfather Alvin, “an evil f—” who “hated joy” beat her in front of her classmates, as she left her job at Billboard to assuage her first husband’s ego, as the Times shut her out for a negative review of Harry Belafonte, there is much she kept to herself: What was that first show like in 1989? How did her mother finally leave Alvin? What is Beyonce like in person?!

Smith’s takes on these women’s lives is assiduous. She uses direct interviews and shoe leather research to patch up what we forget, or were never enlightened to, about these women. Not everyone gets quite the same depth of treatment, and the most vivid chapters are those of women of Smith’s generation—Whitney, Janet, etc.—with whom she spent significant time.

No one book and no one journalist can tell it all. History is a product of many people, and “Shine Bright” succeeds in filling in some of the gaps. But for every woman that gets to shine by Smith’s pen, far more are still waiting in the wings. The more we uncover, the more remain for history to find and hold up to the light.