This story was updated on Oct. 5, 2022 to reflect the latest campaign filings.

California’s largest health care workers union is no stranger to taking its fights to the ballot — both statewide and locally. In the past five years, it has pitched to voters initiatives on issues ranging from staffing at dialysis clinics to price caps for specific health care providers.

This election season, Service Employees International Union-United Health Workers West is targeting the cities of Duarte and Inglewood, where on Nov. 8 voters will decide whether to set a minimum wage requirement of $25 per hour for some of the lowest paid workers at private hospitals, integrated health systems and dialysis clinics. These workers include patient care technicians, janitorial staff, food service workers and aides, among others.

Union leaders are betting that local wins this November could spur a larger statewide movement. Given California’s shortage of health care workers, supporters say a pay bump may help; opponents say these proposals are too narrow to make a difference and may instead backfire.

“We want to win a minimum wage across the state (so) we’re starting off by targeting where we’re hearing the most support and the most need,” said Renée Saldaña, a spokesperson for SEIU-UHW.

The union tried negotiating a statewide minimum wage with hospital leaders this summer, but that deal fell apart. And in the past, the union has pushed to raise the state’s general minimum wage, such as when it authored a $15 minimum wage measure for the statewide ballot. The union withdrew its measure when Gov. Jerry Brown signed a similar proposal into law.

Residents in a handful of other Southern California cities may have to make a decision on health care worker wages in later elections. For example, city councils in Los Angeles, Long Beach and Downey approved minimum wage hikes for health care workers at private facilities this summer. But an industry-backed campaign temporarily blocked the cities from implementing the ordinances after it collected enough signatures for a referendum. Those city councils either must repeal the ordinance or put the issue up to voters, likely in 2024.

The coalition of hospitals and clinics leading the opposition to the wage initiatives is calling the union’s proposals “deeply flawed” and the pay rate “arbitrary.” The hospital lobby and health systems across the state have poured at least $17 million into campaigns to defeat these two measures, according to campaign filings in Inglewood and Duarte. SEIU-UHW has allocated more than $1.2 million in support.

The opposition campaign’s argument to voters is that the measures are bad policy because they exclude a significant amount of health care workers in these cities. The measure applies only to private hospitals, their affiliated facilities and dialysis clinics, meaning workers employed at public hospitals would be excluded. Workers at nursing homes, private or public, are also not included in the measure.

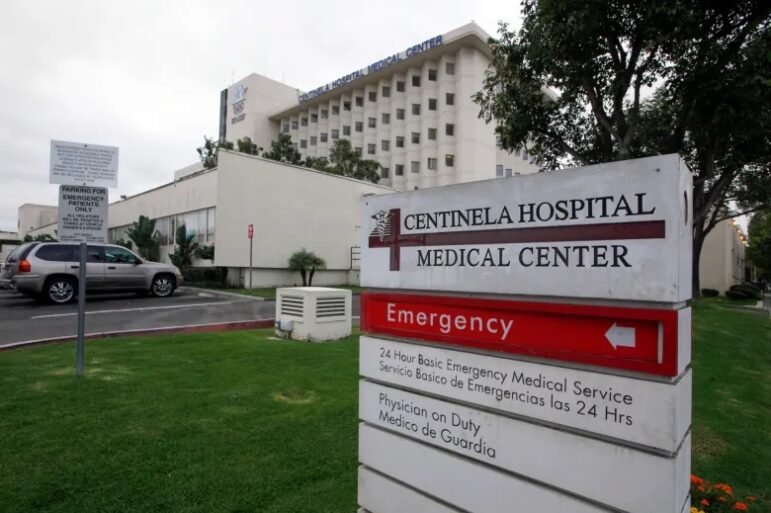

Duarte’s Measure J would primarily apply to people employed by City of Hope, a private nonprofit hospital and cancer research center. In Inglewood, Measure HC would apply to workers at a number of dialysis clinics and Centinela Hospital Medical Center, a 362-bed facility operated by the for-profit system Prime Healthcare.

If approved, the $25 minimum wage rate could go into effect as early as December. Employers would then have to follow up with cost of living increases starting in 2024. The initiatives prohibit employers from funding the minimum wage hike by laying people off or reducing their benefits.

George Greene, president of the Hospital Association of Southern California, warned these measures could financially strain hospitals and lead to cuts in services, hurting patients. Greene argued that by requiring only certain private facilities to raise their minimum wage, health care workers in the area could gravitate toward positions there, exacerbating employee shortages at neighboring, public facilities, which largely serve low-income patients.

“Absolutely, the hospital industry believes that our workforce should receive fair pay. We believe that this should be a statewide conversation so that all health care providers can be taken into consideration and we can have a measured approach as to how we determine what those rates of pay should be,” Greene said.

SEIU-UHW is also behind this year’s Proposition 29, a measure that asks voters statewide — for a third time — to decide on establishing new rules for dialysis clinics, including adding an extra medical provider on site. The union is known to routinely turn to voters and use the initiative process as a negotiating tactic. In the past, the union has proposed ballot measures and then pulled them after reaching agreements with hospital leaders.

In August, the union and the California Hospital Association tried to hash out a last-minute legislative deal that would boost the minimum wage for workers in both public and private facilities statewide (ranging from $19 to $24 an hour, depending on location) in exchange for the union’s support for a request to delay seismic upgrades due in 2030. But those negotiations fizzled.

“These are both big, important issues that must be addressed, but with the end of the legislative session only a week away, we just simply ran out of time this year,” Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokesperson for the hospital association, said at the time.

In absence of a statewide wage deal, the union is targeting its effort where it thinks it can secure support, starting with city councils. Saldaña said cities don’t have the power to implement wage raises at county, state or federally run health facilities, which is why the union has focused its efforts on private systems. The union’s plan is to eventually expand these efforts to all other health care workers, she said.

Saldaña also explained that the union arrived at the $25-per-hour rate because that would place these workers at annual earnings of almost $50,000, which the union considers the baseline income to live in high-cost areas like Los Angeles.

For Mauricio Medina, a wage increase could mean an opportunity to finally have the time to take the courses he needs to become a registered nurse — a longtime goal of his. Medina, a union member, works as a unit secretary at Southern California Hospital at Hollywood. Much of his work is administrative: admitting and discharging patients, taking calls, and organizing information for medical staff. In a week, he usually works three 12-hour shifts at this location. He often picks up extra shifts as an on-call certified nursing assistant at other hospitals, including City of Hope in Duarte and Centinela Hospital Medical Center in Inglewood.

“It’s hard because sometimes you don’t get to see your family. You come home at 9:30 pm, you eat dinner, sleep, wake up and do it all over again,” he said.

Medina has spent 22 years in the field, the last six years in his current position. He said he started his current job at $16.25 and through the union’s contract negotiations is now earning $21 an hour. Still, as the sole provider for his family, this is often not enough.

In the last few years, he has seen a number of coworkers leave for jobs in other sectors with more competitive wages, leaving his workplace even more shorthanded. He understands why they leave — the pandemic burnout along with low pay “brings down my feeling of wanting to stay in the industry,” Medina said. “And I know at any given time, they’re quick to replace me with another body.”

A national survey of health care workers conducted in September of 2021 found that 18% of health care workers had quit since the start of the pandemic and 12% had been laid off. Of those who stayed, 31% had contemplated leaving.

Joanne Spetz, professor and director at the Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco, said a living wage is key to retaining and attracting health care workers, but it’s unclear what the impact of the union’s city-by-city strategy could be.

She explained that a pay bump in private facilities could force public facilities to do the same to remain competitive. But labor economics suggests that in turn, hospitals and clinics will look at where they can make cuts or for ways to recoup costs, Spetz said.

“Health care organizations tend to be pretty good at figuring out how to pass on the costs to insurance companies,” she said, “which means pass on the costs to you and me.”