Throughout history, many have envisaged the Bay Area as a prismatic haven for the misunderstood, the radical, the clairvoyant of a better future. The belief is “here, we are safe, we are free to experiment, we are supported in our endeavors to push on the status quo of identity, artistry and politics.” But that’s not the reality for everyone. The Bay Area fosters the same oppressive systems as anywhere else.

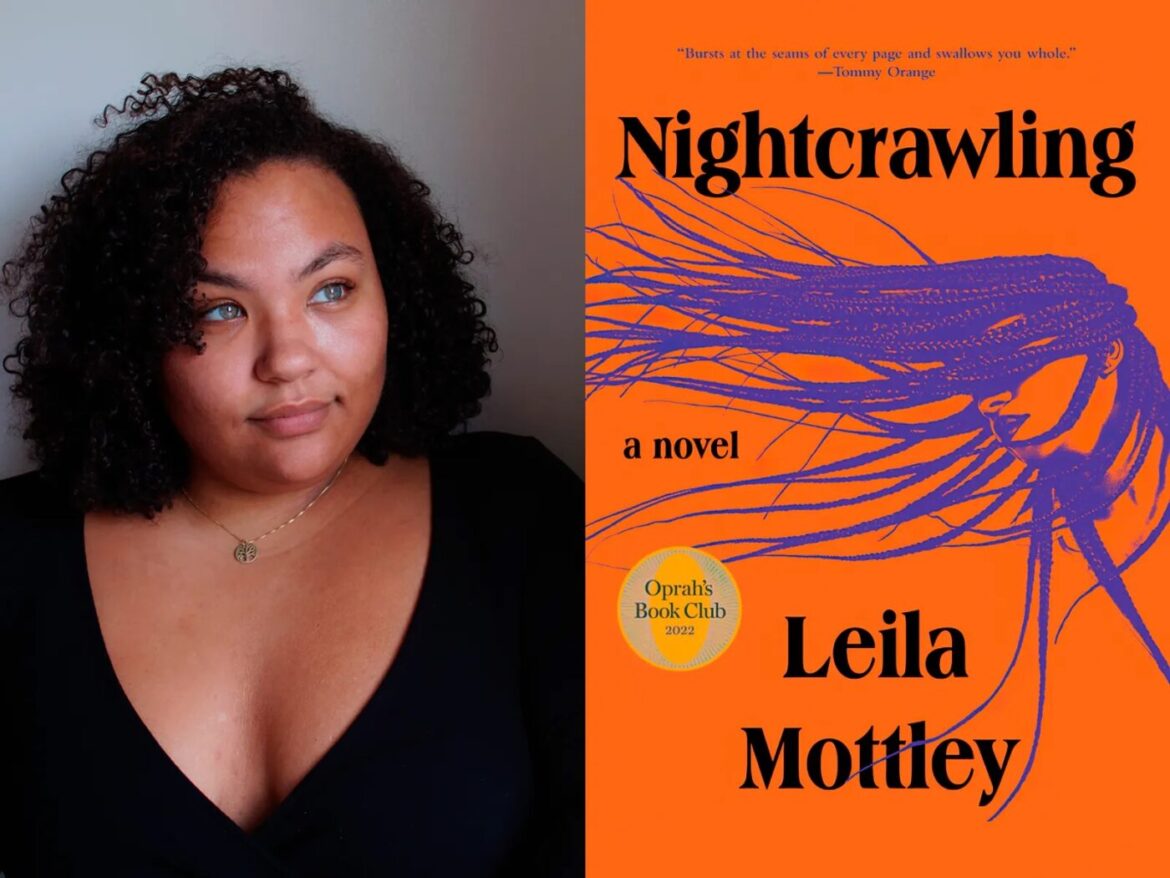

Back in 2016, officers from the Oakland Police Department and half a dozen other East Bay law enforcement organizations faced allegations in a sexual misconduct case involving an underage sex worker, referred to as “Celeste Guap,” that culminated in one officer’s suicide, an internal investigation and a settlement with no charges brought against the officers named. It was a visceral reminder of the vulnerability of girls and young women of color, even in a place as progressive as Oakland — of the distance between what safety means and what it is. Oakland native Leila Mottley, now 20, was a young teenager when the story broke. It would shape her work for years to come, culminating in her debut novel, “Nightcrawling.”

Mottley, who was also the 2018 Oakland youth poet laureate, grew up in an Oakland that bore witness to the turbulence of greed, racism and bureaucratic corruption every day. At the same time, it was a rich bed of soil for her poetry and spoken word, surrounded by artists, hustlers and thought leaders. In “Nightcrawling,” she conjures a world within 17-year-old East Oakland native Kiara Johnson to lay those feelings out. The book has since become a New York Times bestseller, an Oprah’s Book Club pick and part of the 2022 Booker Prize Longlist.

“We often see Oakland only in this very binary way, where it’s either represented by outsiders as a city that is crime-ridden and violent, or it’s a city on the come up that many people are moving to [with] these new, cool restaurants. Both of those views are really narrow ways to see the city,” Mottley says.

“I wanted to be able to capture a place that is so vibrant that it can sometimes feel hard to articulate it. That was important that I could also have that be a component of the narrative around the city.”

Kiara is not Celeste Guap, but she could be anyone you know, anyone you’ve seen on the bus or the uneven sidewalk. Kiara lives with her older brother Marcus in the Regal-Hi apartment complex in East Oakland, a place she feels has been forgotten. He’s also her guardian and, as her interactions with men as clients, manipulators and aspiring suitors unfold throughout the book, the only man she may ever be able to love. Her father, a Black Panther, has died because of compounded medical neglect after serving time he didn’t earn in San Quentin. Her mother is in a halfway house after a suicide attempt and a sentence of her own, stemming from the accidental death of Kiara’s toddler sister, Soraya. Deep breath now; it gets darker.

Kiara is just three months from her 18th birthday when the book opens, with the Regal-Hi pool filled with dog feces. Kiara cannot swim, and the pool has never been cleaned anyway, so this, while disturbing, seems of little consequence. But as she navigates each day, with the dual deadlines of her 18th birthday and the rent increase issued by Vernon, the landlord, no detail is so innocuous. She and her best friend, Alé, attend a local funeral to rifle the coat closet and make a plate of free food, where, for a minute, she can disappear, “a relief to be removed from sight.”

Kiara’s life slowly comes to resemble the pool, filling up with burdensome waste without a way to purge herself. She is a high school dropout without marketable skills she can put on a resume, let alone the means to print one out. One night, after reconnecting with an old friend who bartends at a strip club and serves her alcohol underage, a drunk Kiara’s stumbles into sex work. With rent due, it seems as viable a path as any to keep her and Marcus housed.

There is no one she can tell this to, no one to give her the space to process what has happened or what options she has. Everyone in her ecosystem, even Alé and childhood friend Shauna, have their own rage and anguish to navigate before they even step outside.

But what she figures will be a short stint of disembodied coupling with men she meets on the street soon becomes weeks of stratagems by local police officers who take her to the “Whore Motel” and often stinge on paying her for her time. But how else is she supposed to not only feed herself, but also Marcus and her elementary-age neighbor Trevor, whom she increasingly regards as a surrogate son? Even after she has been named by an officer who committed suicide and the internal investigation begins, her focus is on protecting these two boys in her life before her own body, her own feelings. Kiara begins to see her own body as a means to an end, rather than a vessel worthy of being treasured.

“So when the rent notice got posted, when Polka Dot came up to me and showed me what my body was worth, I thought maybe this was a ticket out for the both of us. Maybe this was how we go free,” Mottley writes of Kiara’s thought process.

Many novels of today about teenagers explore, often deftly, the tribulations of growing up as a digital native, the new eyes that see old problems, how we cultivate identity within a landscape from which we cannot hide. Many of them revolve around familiar and imperfect pillars of adolescents: high school, family, friendship and first grasps at love. But what does youth look like without all of that? What about the millions of youth whose narratives have been splintered and forcibly rewritten, who have no room or place or energy for wondering about who they are?

“We’re socialized, conditioned to exist in this world, and the gendered ways in which we’re raised very much impact our relationships with the people we love and ourselves,” Mottley says. “I wanted to depict an image of Black girlhood that allows for us to see Black girls as vulnerable people, who have needs and who can exist outside of the narrow ways that I think we often see Black teenage girls represented. A lot of that meant being able to show Kiara’s complex interior world.”

Kiara and her story do away with many of the tropes about modern-day teenagers. Kiara does not have a smartphone — she has no access to Instagram or Twitter or even a computer through which she could look for jobs and social services. Her family has been buried, taken into custody or disappeared. She understands the tangible experience of gentrification and police brutality not through classrooms or reading theory, but seeing them, being part of them. Mottley says this was an intentional decision to corner Kiara into her choices.

“A lot of us don’t think of technology or the internet as a resource, but it is,” she says. “[Kiara is] limited by resources into living in her very literal, tangible world. That made even more sense for her character because of how isolated she finds herself. And then she doesn’t really know what other options we have, and it kind of makes the choice even more ambiguous when she doesn’t have access to even the type of resources or knowledge or connection that can help us find more ways to navigate a situation.”

Kiara, in her fullness, is often just as frustrating as she is lyrical. She makes mistakes, rationalizes the unthinkable, snaps at those around her who may not always deserve it. There are times, like her reverence for Camila, a sex worker who tries to set her up with a pimp, that warrant questions such as “Why doesn’t she know better? How does she not see this for what it is?”

Because she is a child. And that chasm, that gaping space between what she should know and what she believes she can do, is perhaps the darkest realization, even as Oakland police officers rape her at gunpoint. Even as she begs her brother to stop filling his afternoons with studio sessions and get a job. She has no one to show her things could be any different. No one could call Kiara dumb: She has been clutching at survival since her father died, she is raising Trevor, the son of her neighbor Dee, who has relented to her addictions.

Teenagers without resources

Despite being written by Mottley as a teenager about a teenager’s experiences, “Nightcrawling” is not classified as a young adult novel, with its frank perspective on sex trafficking, poverty and the internal rot of the justice system. Still, Kiara’s youth is a key part of the story. As she states late in the book while being cross-examined for a trial we know has no real interest in justice, “They looked at me and they saw how small I was. I was a child.”

Kiara’s story bears a passing resemblance to another East Oakland-set novel about the cracks youth fall through in abandoning the bliss of innocence to survive, Keenan Norris’ “The Confession of Copeland Cane.” Both are centered on children in dismal circumstances that are set to get worse. Both Cope and Kiara deserve a protection they can’t afford; they both engage unwillingly with the police and are forced to learn just how small the world wants them to be. But Kiara’s story has the additional wrinkle of her gender, and she must relinquish her virginity and the last tendrils of peace to ensure those she loves can get by.

Mottley tells Bay City News that while the Celeste Guap trial was a spark, Kiara’s story is not really about that, and it only makes up about a third of Kiara’s journey. Rather, she frames the book as a young girl’s descent into and her open-ended escape from nihilism. Her refusal to relent to the weight of it all.

Media coverage for “Nightcrawling” often centers on Mottley’s precocious age and her depth of skill despite it. But to be the youngest, as to be the first, is a lot of pressure. Mottley still lives in Oakland, with no plans to move anytime soon. Book No. 2 is in the works, and she writes nearly every day. Mottley likes quiet, inhabiting her characters and letting them breathe their stories through her. That’s harder to do when late-night hosts and journalists are flooding her channels, but nothing she can’t make space for.

“It’s kind of a double-edged sword because I feel like, on the one hand, I totally get the fascination with my age,” she says. “At the same time, I always wonder, ‘Are we fascinated by it because we don’t expect much from young people? Is that because young people aren’t doing brilliant things, or is it because we don’t uplift or even look at young people as important or valuable?’ I hope that helps us to remember that young people are people. I’m not an anomaly in that way.”