Kings County Supervisor Joe Neves guided his pickup to a stop next to a long line of chain-link fencing. On one side of a gravel road stood row after row of glinting solar panels. The automated mirrors pivot and turn, following the sun in its daily path across the Central Valley sky.

Neves, a big man with a wispy Santa Claus beard, was showing off the county’s newest mega solar power project, still under construction on 1,600 acres. A state-of-the-art facility, it includes powerful batteries to store and deliver power after the sun sets.

This solar plant in King County is one of the scores of new renewable energy puzzle pieces across the state considered vital to California’s transition to cleaner electricity and its pursuit of climate change solutions.

Rural California counties like Kings — with lots of land, sunshine and wind — are the focal point for many of these projects. Now they are at the epicenter of a statewide controversy, too.

Last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom pressured lawmakers to approve an energy plan that aimed to expedite and streamline construction of new clean energy facilities. Included is a controversial clause that lets developers bypass local permitting and instead turn to the California Energy Commission for fast-track approval.

The new strategy is an end run around local authorities who sometimes balk at allowing wind and solar facilities in their own backyards.

But if Newsom sees small, rural counties as impediments, Kings County begs to differ. Neves and other local officials have been busily opening up their county to solar projects for more than a dozen years.

Far from scoffing at the idea of renewable energy, some Kings County farmers have embraced solar generation as a profitable problem solver – they get paid for the use of their barren land and can transfer the water to higher-value crops.

Whatever the intent of the new law, Kings County doesn’t think it’s the problem: Most projects in the county’s 40,000-acre solar zone receive approval in less than six months — in some cases in six weeks, county officials say.

“We are not unsophisticated, we know what we are doing,” Neves said. “We planned for this. We can see the future.”

Across the state, local officials were miffed at state officials for being excluded from the discussion as the law was being crafted behind closed doors in late June, then piqued again after it passed the Legislature and was signed by Newsom, meaning they no longer had the final say-so for projects in their counties.

“Local governments are viewed as an impediment, another layer you have to go through to get your project across the finish line. But we permit these facilities all the time. It’s one of the core functions we perform as local government,” said John Kennedy, a lobbyist for Rural County Representatives of California, which advocates for 39 small counties.

“To have that authority taken out of our hands and given to the Energy Commission — that much farther from the people, that much removed from local sensitivity — to have that authority clawed back is really painful,” he said. “We’re in the crosshairs, but we don’t think we are the right target here.”

While a few projects have been stalled by local officials, some energy developers said Newsom’s initiative is a solution in search of a problem.

“What is this proposal solving for?” said Alex Jackson, director of California state affairs for American Clean Power, an association of renewable energy companies.

“In general we work really well with local government. We have invested a lot in those relationships. We prefer to work with them rather than strong-arm them. Overall we don’t see this as unlocking the path to accelerating clean energy.”

In his signing statement attached to the new bill, Newsom said the unprecedented pace of climate change means California must move faster to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels. The state must begin producing 50% more clean power in the next decade in order to meet its goals.

The new law, Newsom wrote, will “support and expedite the State’s transition to clean energy projects and help maintain energy reliability in the face of climate change.” The fast-track option through the Energy Commission promises developers a decision within 270 days and bypasses local approval.

The new strategy, Newsom wrote, will help keep the lights on when demand peaks from extreme heat and drought, which are putting “unprecedented stress” on the state’s power grid. “Action is needed now,” he said.

Kings County: A prime place for generating energy

Kings County, population 152,486 and home to Hanford and Kettleman City, is well-situated to host renewable energy projects: It’s at the nexus of major north-south and east-west transmission lines and its power plants can readily dispatch electricity to the grid.

Solar projects already built on Kings County’s fallowed farmland are helping power Disneyland, and the newest development, called Slate Solar and Storage, will supply about 900 megawatts of electricity when it’s finished. Some will go to two Bay Area powerhouses: The BART transportation network and Stanford University.

Occupying former watermelon, cotton and corn fields fallowed by drought, developers are building solar farms in Kings County as fast as the world’s crippled supply chain will allow. To expedite the process, local planning officials created solar energy zones that have already been fully vetted and undergone comprehensive environmental analysis.

The county has more than 21,000 acres of solar development, and the land, mostly private property, is leased or sold outright to companies.

Faced with rapidly rising energy costs, school districts and towns are investing in their own small-scale solar projects, Neves said, as have farmers looking for cheap ways to pump water and run equipment.

“A humongous task”

Whether funneled through the Energy Commission’s new process or approved by local authorities, new renewable energy development will have to come fast.

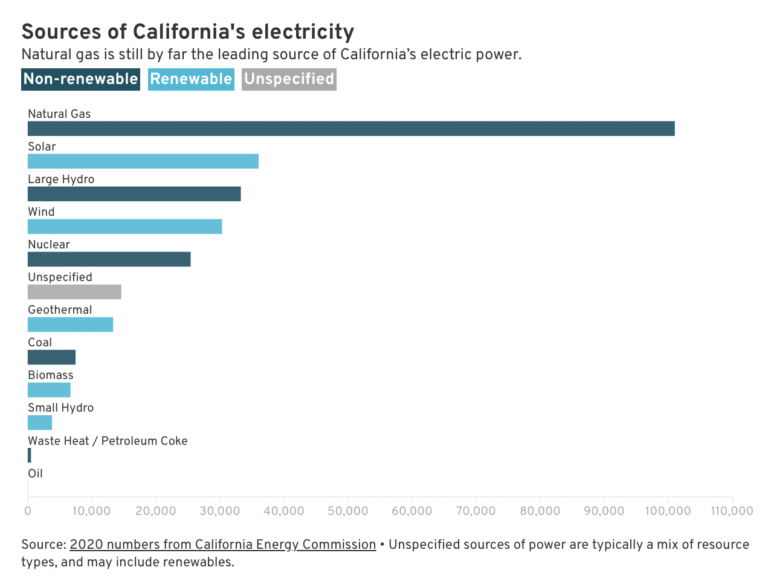

Although California is well ahead of its interim goals for clean power – about 34% of its generation last year – getting to carbon-free by 2045 will be a challenge of the highest order.

With worsening climate models, electrification of transportation and buildings, the drought-driven crash in hydroelectric power, and the scheduled closure of fossil-fuel power plants, the sobering reality in California is this: At current rates the state will produce 40 gigawatts of clean power annually over the next decade, while preliminary projections show it needs 60 gigawatts a year — at a minimum.

The need, given how rapidly demand is growing, is likely to increase.

“It’s a humongous task,” said Siva Gunda, vice chair of the California Energy Commission. “We’ve had 100 years to build the grid the way it is today and we’re redoing it in the next 20 years. At least we have a plan. We are digging ourselves out of a hole.”

The scope of what’s required means California will need to greatly expand its renewable footprint. With the most obvious and cheapest sites already developed, the way forward will be achieved one sunny, windy acre at a time.

Experts say residents can expect to see energy development in parts of California where solar panels and wind turbines have not yet sprouted. That expansion is likely to challenge the hospitality of rural communities and their elected leaders, especially when they feel excluded from the process.

Such pushback is not unexpected. Research published in June found that when local groups believe they are not consulted on renewable energy projects in their communities, they push back hard. The researchers concluded that the best way to get local buy-in is to listen to local voices.

Although the state law is new and its implications not yet fully understood, Jackson said the early message is “loud and clear from my developers: They want to continue with the local process. The (Energy Commission) route is not that attractive. When you unpack the proposal, it seems to fall short.”

Some local representatives predicted a cascade of lawsuits from local authorities will follow. The law “created an enemy of local government and may unhelpfully exacerbate existing (anti-Sacramento) sentiment,” Jackson said.

Local pockets of resistance

A few California counties are firmly against some renewable projects: In 2015 Los Angeles County banned wind turbines in unincorporated areas such as the Antelope Valley and Santa Monica Mountains.

And three years ago, San Bernardino, the state’s largest county, outlawed solar and wind farms on more than a million acres in unincorporated communities where industrialization is deemed incompatible.

Residents feared construction disturbance and dust, and expressed more aesthetic concerns, said David Wert, spokesman for the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors.

“Folks that live in these small communities don’t want to wake up and look at a large solar farm out their window,” he said.

Mark Lawler, vice president for development at ConnectGEN, a Texas-based renewable energy developer, said not-in-my-backyard sentiment led to the rejection of his company’s projects in Humboldt and Lake counties.

With wind turbines, he said, “there’s a visibility issue. ‘If I can see it, I don’t want it.’ It’s not unique to California or any of these rural counties.”

The issue also drove the recent denial of ConnectGEN’s Fountain Wind project in Shasta County, which was proposed to go in on a high ridge adjacent to an existing wind project. Local opposition ran the gamut, from concerns about the views to fears that tall turbines would make it impossible for air tankers to fight fires on surrounding mountains.

Lawler said project managers made 76 changes to the plan, including reducing the turbines’ height and moving them from the most visible locations. He said the project would enhance fire safety by clearing vegetation around roads and the turbines. It had the potential to power more than 86,000 homes, according to the company.

“The benefits to the county would be overwhelming, millions of dollars infused to the economy, police, jobs and property tax,” Lawler said. The company donated $3 million to local organizations, a common strategy among renewable developers to gain favor in communities.

“We would hire local labor, we did everything I could come up with. We are literally building Phase 2 of an existing wind project that’s been there operating safely for 10 years,” he said.

Still, the development ran into fierce opposition, including from environmental groups. The wind farm would have been in the district of Shasta County Supervisor Mary Rickert, who called it “unsightly” and said it was foolish for the developer to try to site its turbines on the ridge. “I don’t know what they were thinking,” she said.

After denying the permit, the supervisors considered imposing a moratorium on wind energy systems in some parts of the county. The board sent the proposal back to the planning commission “to put more meat on its bones,” Rickert said. She said if the moratorium proposal returns to the board, it will be passed.

Rickert said the pushback in the region has nothing to do with opposition to renewable energy. And as for doing its part to help the state achieve its clean-energy goals, she noted the county’s contribution to hydroelectric power: “We’ve got Shasta Dam.”

Nancy Radar, executive director of the California Wind Energy Association, said she understands the concerns of local groups but said they need to be balanced against the imperative to build clean-energy projects.

“There’s a mismatch between statewide goals and leaving those decisions to local communities,” she said. “Some people are being left behind. Disadvantaged communities are suffering greatly from fossil fuel impacts, and then we have other people who can’t handle a wind turbine in their viewshed. We have to keep the relative impacts in mind.”

The idea that opposition to renewables follows a political, red-blue divide doesn’t play out across the state. Conservative Kern and Riverside counties are “built-out” Rader said. Kern, for a century the state’s provider of fossil fuels, has extensive renewable energy projects.

What Kern County officials and others balk at, though, is a statewide law that exempts solar projects from property taxes, denying local governments operational cash. Neves, from Kings County, estimates the solar tax break costs his region some $3 million a year. The law is set to sunset in 2025 but a similar measure is making its way through the Legislature. (Wind projects are not offered similar tax breaks.)

But rather than providing an advantage for solar projects, the tax exemption establishes a disincentive for local jurisdictions to approve the projects, said Catherine Freeman, legislative staffer for the California State Association of Counties. “Those property taxes pay for basic county government,” she said.

Gunda of the Energy Commission said the state established a task force last year to better understand the broad obstacles to ramping up renewable projects. Its work is still underway but Gunda said there have been significant construction delays from COVID-19 and supply chain breakdowns.

However the new law plays out, the urgency is obvious, said Shannon Eddy, executive director of the Large Scale Solar Association. She said county and state officials and energy developers should build a statewide model to help smooth the process of siting new energy plants.

“It’s neither fair nor correct to point to the counties and say therein lies the problem,” she said. “Everyone needs to help. Everyone needs to come together to make this happen. We’re building the airplane as it’s running down the runway.”