THE BAY AREA is one of the most diverse regions in the United States. People of color became the majority of the population in the region around 1980, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, around 65 years before the United States will be majority people of color.

Today, 27 percent of Bay Area residents — around 2 million people — identify as Asian American or Pacific Islander, and the population is expected to grow rapidly in the coming decades.

But Asian Americans — whether immigrants or native-born — include a variety of ancestral backgrounds and cultures and live in different parts of the Bay Area. A new study by Bay Area Equity Atlas shows how AAPI populations are distributed across the region by separating data based on ancestry. Through a series of maps, the study highlights key differences within broad racial and ethnic groups living in the Bay Area.

Chinese: Presence dates to the Gold Rush

Consider people of Chinese ancestry in the Bay Area, a group who make up 30 percent of the AAPI population in the region. Chinese communities are located throughout the Bay Area but are primarily concentrated in San Francisco and Oakland.

Within the Bay Area, the number of residents with Chinese ancestry differs significantly by county. Chinese residents in San Francisco County make up 53 percent of AAPI residents compared to the regional average of 30 percent, while Chinese residents in Napa and Solano counties make up 8 and 7 percent of the AAPI population respectively.

The Chinese were the first Asian immigrants to come to the U.S., arriving through the ports of San Francisco when the Gold Rush began in 1848. When the rush dried up, Chinese immigrants moved eastward to work on the Transcontinental Railroad built in the 1860s connecting Iowa to Oakland.

Everything changed for Chinese immigrants in 1882 when the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law, prohibiting Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S. for 10 years. By this time, anger and violence against Chinese people was on the rise across the U.S.

“The Chinese were driven out of towns across the United States,” said Jonathan H. X. Lee, a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University and the author of a book about the history of Asian Americans in the United States.

“There were many cases of Chinese being driven out of the Pacific Northwest through Oregon and Washington and throughout the South and the Midwest. So, they went to San Francisco or Los Angeles or Oakland as their ‘safe space,’” Lee said.

The period of exclusion extended far into the 20th century, until the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act that abolished the favoring of immigration from Western and Northern Europe.

But it wasn’t until the 1980s, according to Lee, that the Chinese populations scattered across the Bay Area immigrated to the region.

The first wave began in the decades leading up to Hong Kong’s transfer from British to Chinese control in 1997.

“They weren’t sure what was going to happen to Hong Kong when it was given back to China. So many came [to the U.S.] but they didn’t go to San Francisco itself, because it had lower socioeconomic status immigrants. The Hong Kong migrants actually had money and were highly educated, so they settled in the South Bay region,” Lee said.

Taiwanese immigrants, who also came to the U.S. with wealth and resources, began settling in Cupertino and Palo Alto in the 1990s.

“This is what the map doesn’t tell you in terms of the diverse demographics of Chinese communities in the Bay,” Lee said. “By the 2000s, many of the Chinese immigrants came from the mainland to San Bruno, San Mateo and Millbrae,” Lee said.

Chinese immigrants from the mainland continue to come to the Bay Area in large numbers. Many settle in suburban areas with professional rather than family visas, leading to a socio-economic urban-suburban divide among Chinese communities in the Bay Area.

Japanese: Dislocated during internment

The Japanese were the second Asian population to immigrate to the Bay Area in large numbers. Today, residents with Japanese ancestry make up a small share of AAPI groups living in the Bay Area at 3.2 percent of the population. This is because Japanese families were displaced during internment, and many relocated to the Central Valley instead of coming back to the Bay Area.

Japanese residents are more widely dispersed than other Asian communities, with small populations in counties across the region. Japanese residents make up higher shares of AAPI populations in Marin and Sonoma counties at 10 and 7 percent respectively.

According to Lee, the Japanese populations in the Bay Area reflect an older generation of immigrants.

“These are all very well established Japanese American communities with links to the first wave of Japanese migrants. So, there’s second and third generation Japanese Americans in a lot of Bay Area communities today,” Lee said.

Japanese began coming to the U.S. after Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Because Chinese migrants were no longer welcome in the U.S., more than 400,000 Japanese migrants came to Hawaii and the Pacific Coast, according to the Library of Congress.

The Japanese did not meet the same fate of exclusion as the Chinese. By the early 20th century, Japan was a rising Asian power and negotiated an informal “gentleman’s agreement” with the United States to ease racial tensions in 1907-08.

Through the agreement, President Theodore Roosevelt forced San Francisco to repeal its Japanese American school segregation order in exchange for Japan denying passports to Japanese laborers.

“This was huge because the Japanese knew how the Chinese were treated. Their government had power, which was why Japan was able to bend the U.S. to its will,” Lee said.

Nevertheless, Japanese labor migration to the United States stopped early in the 20th century and did not pick up again partly because Japan has not experienced a population boom like other East Asian countries that contribute to large influxes of immigrants to the Bay Area.

According to Lee, some Japanese are coming to the U.S. on professional visas, but most Japanese residents in the Bay Area are well-established communities descended from the first wave of Japanese immigrants to the region.

Koreans: From farming to technology

Korean laborers came to the United States to work on farms along the West Coast following the “gentlemen’s agreement” between Japan and the United States.

Today, Korean residents make up 3.6 percent of the AAPI population in the Bay Area and live throughout the nine-county Bay Area. Korean residents account for less than 5 percent of the AAPI population in most counties except for Sonoma, where they make up 6 percent.

Large communities exist in the Sunset and Richmond districts of San Francisco, in Silicon Valley cities like Mountain View, Sunnyvale, Santa Clara and Cupertino, and in East Bay cities like Berkeley and Walnut Creek. Smaller communities of Koreans also live in inland communities of San Ramon, Dublin and Pleasanton.

Many Koreans who came to the U.S. to work on farms in the early 20th century converted to Christianity.

“Labor recruiters were saying, well, they’re Christians, so they aren’t like the other heathens,” Lee said.

But that argument didn’t work for long. Within a decade, Korean immigration was restricted, and South Asians began to immigrate to the U.S. to replace Korean farm labor.

After the immigration reforms of 1965, South Koreans came to San Francisco and spread across the Bay Area. South Koreans nurses were recruited in large numbers to work in health care, and a fresh wave of immigration began in the 1990s as high-skilled South Korean workers came to Silicon Valley on professional visas to work for technology companies.

Indians: Asians by court decree

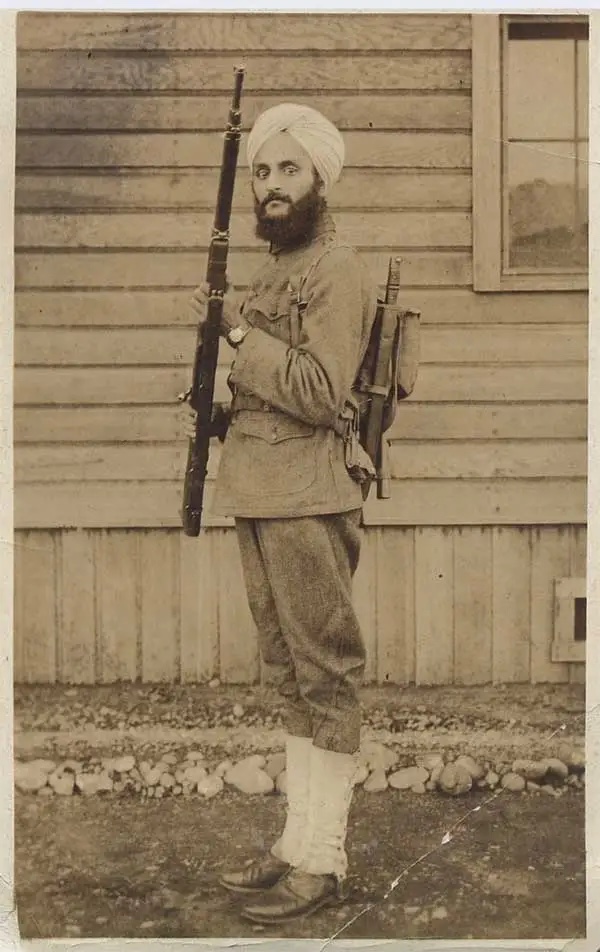

Following bans on Korean immigration to the U.S., a large wave of Punjabi immigrants from Indian came to San Francisco.

Today, Indians are the second-largest AAPI group in the Bay Area, accounting for 16.4 percent of the population. Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin and Santa Clara counties are home to similar or slightly smaller shares of Indian residents than the regional average, while Indians in San Francisco and San Mateo counties make up less than 10 percent of the AAPI population.

The first wave of Indian immigrants to the Bay Area ended up settling in the Central Valley, while others stayed in Berkeley and at the outer stretches of the Bay Area in Oakley, according to Lee.

From the 1920s onwards, Indian immigration to the U.S. waned because Indians were classified as Asian in the Supreme Court case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind.

The Supreme Court ruled that Thind did not fit the definition of “white” in the eyes of the “common man,” and thus South Asians were to be considered Asiatic rather than Aryan or Caucasian for immigration purposes.

“So first [immigration restrictions] were only for the Chinese and then it included the Japanese and the Koreans and then finally, by 1923, it included South Asians. So, from that period to 1965, when the Immigration Reform Act was passed, a few hundred diplomats and students came to the U.S. every year, but nothing like before,” Lee said.

The map of Indians in the Bay Area today shows that the population is concentrated in Silicon Valley and East Bay cities. This, according to Lee, is a product of the H1B visa phenomenon beginning in the 1990s when technology and pharmaceutical firms began hiring foreign workers with specialized knowledge from India, Korea, China and other countries.

“The H1B visa is not counted towards the annual quota of 10,000 from India. So that would explain why Asian Americans are the fastest growing demographic in the United States right now,” Lee said.

The Bay Area is also home to other South Asian communities, with Pakistani communities in Fremont and East Bay cities like San Ramon, Dublin and Pleasanton. Overall, Pakistani residents make up a relatively small share of the AAPI population in the region at 1 percent and make up a similar share across several counties including Alameda, Contra Costa, San Mateo and Santa Clara.

There are Nepalese communities in Sunnyvale, Berkeley and El Cerrito, and Sri Lankans live in Antioch. Small Bangladeshi communities live in Concord, Livermore and Oakland.

Filipinx: Recruited as farmers, nurses and teachers

Following bans on South Asian immigration to the US in 1923, Filipinx immigrants began coming to the U.S. later in the decade during the Great Depression.

Filipinx residents now make up 15.9 percent of the AAPI population in the Bay Area — the third largest after Chinese and Indian residents. Filipinx residents make up half of AAPI residents in Napa and Solano counties.

“Labor recruiters from plantations stopped going to India and started recruiting from the Philippines,” Lee said. “The Philippines was technically a U.S. territory because the U.S. colonized the Philippines. So, when Filipinos came over to the U.S., they came as U.S. nationals.”

Filipinx immigrants worked on farms along U.S. Highway 101 and in Santa Clara, San Jose and Milpitas, but faced racism and exclusion that led to Congress passing the Tydings-McDuffie Act in 1934.

The act promised independence to the Philippines in 1945. The change in status of the Philippines allowed Congress to impose an immigration quota of 50 people per year, ending the influx of Filipinx immigrants to the U.S.

“The Philippines was technically a U.S. territory because the U.S. colonized the Philippines. So, when Filipinos came over to the U.S., they came as U.S. nationals.”

Jonathan H. X. Lee, San Francisco State University

Jonathan H. X. Lee, San Francisco State University

Thirty years later, when the 1965 Immigration Act was passed, Filipinx immigrants came to the U.S. in large numbers.

“They had their own 10,000 quota, but at the same time the U.S. was recruiting a lot of Filipino nurses to fill our health care need. That led to the spread of Filipino communities everywhere,” Lee said.

In the Bay Area, Filipinx immigrants settled in Daly City and the South San Francisco area.

“Daly City is known as the Filipino capital in the United States,” Lee said. “There are so many institutionalized Filipino businesses that it attracts new migrants from the Philippines.”

Among those new migrants are teachers, who are being recruited to American cities to make up for teacher shortages, Lee said.

Today, Filipinx communities are widely distributed throughout the Bay Area. The Parkmerced, Outer Mission and Excelsior neighborhoods of San Francisco are densely populated with Filipinx residents.

In the South Bay, there are large Filipinx populations in Milpitas and East San Jose. In the East Bay, Union City and Hayward have pockets of Filipinx residents. Hercules and Vallejo are also home to large concentrations of Filipinx communities.

Vietnamese: Reinventing community in the Bay Area

Another Southeast Asian group found widely across the Bay Area are Vietnamese Americans. Vietnamese residents in the Bay Area make up 8.4 percent of AAPI residents but represent around 16 percent of the AAPI population in Santa Clara County — around double the regional average.

Vietnamese people began coming to the U.S. in large numbers when the U.S. left Vietnam in 1975.

According to Lee, the story of Vietnamese migration to the U.S. includes two migrations — one across oceans and another within the United States.

“The U.S. resettlement strategy during this period was to put refugees in all 50 states so that no one community was burdened,” Lee said. “But in retrospect, this was not a good way to do it, because when we put them together, they can usually support one another, but when you put a few refugees in a rural community they become alienated.”

After Vietnamese refugees were resettled across the U.S., a secondary migration occurred. Vietnamese families moved from across the U.S. to Orange County in Southern California and to San Francisco to find Vietnamese community.

In the Bay Area, Vietnamese refugees were flown into Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield and housed in the Tenderloin and Richmond neighborhoods. Many of these communities ended up moving to San Jose, where a Vietnamese real estate agent built a mall attracting Vietnamese businesses from across California.

Most of the Vietnamese refugees who came to the U.S. immediately after the fall of Saigon had some connection to the U.S., according to Lee.

“They were better off in socio-economic status, they spoke English and French, and so they came to the U.S. and settled in pretty well,” he said.

But from 1976 to the early 1980s, Chinese-Vietnamese refugees left Vietnam in boats because of persecution by the communist government, causing an international refugee crisis that coincided with an American recession.

The new wave of Chinese-Vietnamese refugees were housed in low-income projects in San Francisco, which explains why the Tenderloin has a Little Saigon.

“That Little Saigon in the Tenderloin is Chinese Vietnamese, not just Vietnamese,” Lee said. “It’s not completely ethnically Vietnamese or ethnically Chinese. It reflects this unique demographic of a community alienated from the Chinese in San Francisco and the Vietnamese living in San Jose.”

Today, San Jose and Milpitas are home to one of the largest Vietnamese communities in the United States. In San Francisco, Vietnamese residents live in the Sunset and Richmond neighborhoods and in parts of the Polk and Civic Center neighborhoods near Little Saigon.

There is also a large concentration of Vietnamese populations in Alameda and Oakland.

Southeast Asians: Affected by political unrest

Smaller Southeast Asian communities live across the Bay Area. Thai communities live in the Financial District, Polk, the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods in San Francisco. Burmese communities live in Daly City and Fremont. Laotian populations live in Richmond, El Sobrante, Pinole and Hercules. Malaysians live in Brisbane, San Jose and Livermore. Hmong communities live in Concord, Walnut Creek and San Jose, and Cambodian populations live in parts of Oakland and East San Jose.

According to Lee, Laotian and Cambodian migrants came to the U.S. because of events following the American withdrawal from Southeast Asia in 1975.

“The U.S. not only pulled out of Vietnam in 1975, but also Laos and Cambodia, leaving a power vacuum. Then there was a sweep of red and the communists took over Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia,” Lee said.

Refugees left these regions in the late 1970s and following the Cambodian genocide in the 1980s. They were resettled in Richmond, San Pablo, Pinole and Hercules, and in low-income housing and projects in Oakland.

Thai immigrants came to the Bay Area in the 1980s and 1990s to work in health care, followed by more recent influxes of Burmese refugees fleeing civil war during the late 1990s and 2000s.

“If there’s a temple, you’re going to have a lot of Thai, Burmese and even Laotian residents living there because the temple is the heart of their communities,” Lee said, pointing to Burmese settlement in Mountain View near a Burmese temple and Laotians living near a temple in Richmond.

Pacific Islanders: Contention around unique identity

The Bay Area Equity Atlas report includes a map showing the distribution of Pacific Islanders in the Bay Area, who are a diverse but small population including Tongan, Samoan, Native Hawaiian, Guamanian/Chamorro, and others.

Pacific Islanders together make up 2 percent of the AAPI population in the Bay Area, and are concentrated in San Francisco, East Palo Alto and Hayward. Pacific Islanders are more concentrated geographically in the region than other groups, with communities living in the Bayview, Hunters Point, Visitacion Valley and Parkmerced neighborhoods of San Francisco. Along the Peninsula, there are concentrated communities in San Bruno, Millbrae, Burlingame, East Palo Alto and San Mateo.

In the East Bay, Pacific Islanders are more widely dispersed in Oakland, San Leandro, Hayward, Union City and Fremont.

But Lee says that census data collection methods that lump together Asian American and Pacific Islander communities are controversial.

“Pacific Islanders don’t like to be lumped in with Asian Americans. The acronym Asian Pacific Islander American is actually contentious. There’s not a lot of agreement around it [because] Pacific Islanders have their own unique history and experiences being indigenous to U.S. territory,” Lee said, adding that he does not include Pacific Islanders in his publications out of respect for their sovereignty.

The big picture is that Asian Americans are diverse and live in regions across the Bay Area for unique and intersecting historical reasons.

The full Bay Area Equity Atlas study can be found online.