The teacher shortage has struck most districts in California, but an EdSource survey shows that the impacts are nuanced, uneven — and sometimes inequitable.

Even within the same district, some schools — particularly those in wealthier neighborhoods — experienced less teacher turnover and were more likely to start the school year with a full staff.

Meanwhile, many districts that serve large numbers of high-needs students reported severe teacher shortages as the school year began, leaving students with substitutes or administrators to fill in until the district could hire more staff.

“The teacher shortage is not a mass exodus story. There’s variation,” said Desiree Carver-Thomas, researcher and policy analyst for the Learning Policy Institute, who’s studied the issue. “But there are very significant shortages in some districts, and that’s having a big impact on students.”

In Santa Ana Unified, for example, where almost 90% of students are low-income, the district reported 52 teacher vacancies last week, almost half in special education, a notoriously hard-to-staff division. That may seem insignificant for a district that has more than 2,300 teachers on the payroll, but those vacancies have left district leaders scrambling. If they can’t find enough substitutes, the district plans to reassign those students to other classes.

It’s not that Santa Ana isn’t trying. So far, they’ve hired 75 teachers for the 2022-23 school year, in addition to 318 teachers they hired last year.

“Santa Ana Unified continues to experience the same, if not greater, shortage of applicants for both certificated and classified positions,” district spokesperson Fermin Leal said, noting the tight competition among neighboring districts to recruit and hire teachers quickly. “We are proud of all the applicants who have chosen and who do choose to work with SAUSD.”

Long Beach Unified, where more than 66% of students are low-income, also reported a severe teacher shortage. Even after hiring 277 teachers over the summer, the district still has 45 vacancies.

Oakland Unified, which has about 20,000 fewer students than Long Beach, has 34 vacancies after a hiring binge of 474 teachers.

The teacher shortage is not unique to California, and in fact, California isn’t even among the most impacted, according to research from Brown University’s Annenberg Institute. Mississippi, Alabama, West Virginia, Kansas and numerous other states all face dire shortages as the school year begins, according to the report. Teachers everywhere have been quitting, sometimes even in the middle of the school year, citing the stress of working through Covid, an uptick in student misbehavior after the return to in-person classes and a lack of respect from parents, among other complaints. A February survey by the National Education Association teachers union found that 55% were seriously considering leaving their jobs.

Combined with new funding to expand staff, many districts have been left with greater-than-expected hiring needs. And those subjects that were difficult to staff even before the pandemic — such as special education, bilingual education, math and science — are even more impacted now.

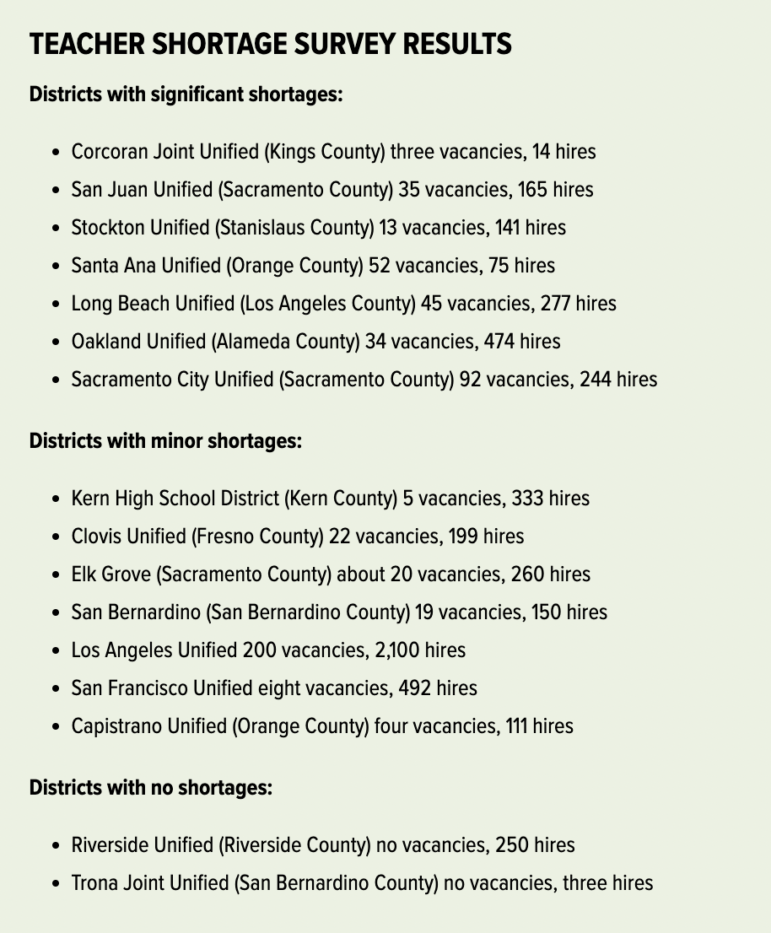

EdSource collected teacher hiring data from 16 districts representing a sampling of California: urban, rural, coastal, valley, large, small, affluent, and low-income. Every district but two (Riverside Unified and Trona Joint Unified near Death Valley) reported a shortage of some kind. Seven said they had nearly filled all their vacancies, while the remaining seven said they were experiencing steep shortfalls.

San Francisco Unified managed to fill all but eight of 500 vacancies by the start of the school year, in part by offering bonuses of up to $2,000 for teachers to work in special or bilingual education or in academically low-achieving schools.

Los Angeles Unified made headlines last week when it announced it had filled 99% of its teacher vacancies. Clovis Unified, near Fresno, said it had 22 vacancies when school started, but the district expects to fill those positions soon.

“We are not seeing any extreme teacher shortage like what’s happening in other parts of the state. We’re actually in pretty good shape for our hiring,” said district spokesperson Kelly Avants. “Even when you look at some of the STEM areas and advanced math and science in high school, we’re fully staffed in those areas right now.”

Some districts in California, such as Fresno, have been grappling with teacher shortages for years and had already embraced creative ways to attract and retain teachers. Bonuses, money for home down payments and student loan forgiveness were among the tools districts used to lure potential teachers.

Those districts had also established close relationships with local colleges to create a seamless transition from a credential program to employment. Fresno went a step further and opened “teacher academies” in high schools, so students can get a jump-start on their teaching careers while still students themselves.

Districts that have been proactive about hiring find themselves in better shape now, Carver-Thomas said.

She also credited the state’s efforts to bolster the teacher pipeline. The new Golden State Teacher Grant Program offers up to $20,000 for those pursuing teaching, counseling or school social work degrees. Salary increases, retention bonuses and teacher residencies also help.

“It did seem to make a difference,” she said.

Riverside Unified bucked the trend. The district has a high percentage of low-income students — 72% — but has not struggled to fill positions like many districts with similar demographics.

Kyley Ybarra, assistant superintendent of personnel, said her department has been trying to increase the teacher pipeline for years. The district has boosted salaries to compete with neighboring districts, raising the starting salary for a new teacher to $66,933. They’ve also lowered class sizes, added professional development courses and offered to pay for the second step of teachers’ credential process, which can cost up to $10,000.

But the biggest help has been the district’s relationship with its three local universities, Ybarra said. By providing student-teaching jobs for college students, the district has seen a big boost in prospective teachers applying for jobs after they graduate.

The district still has to hire hundreds of teachers a year, typically, but college partnerships relieve much of the stress, Ybarra said.

“They get to know us, they feel comfortable, and many decide they want to stay,” Ybarra said. “It’s a lot of work, but it’s made a world of difference.”