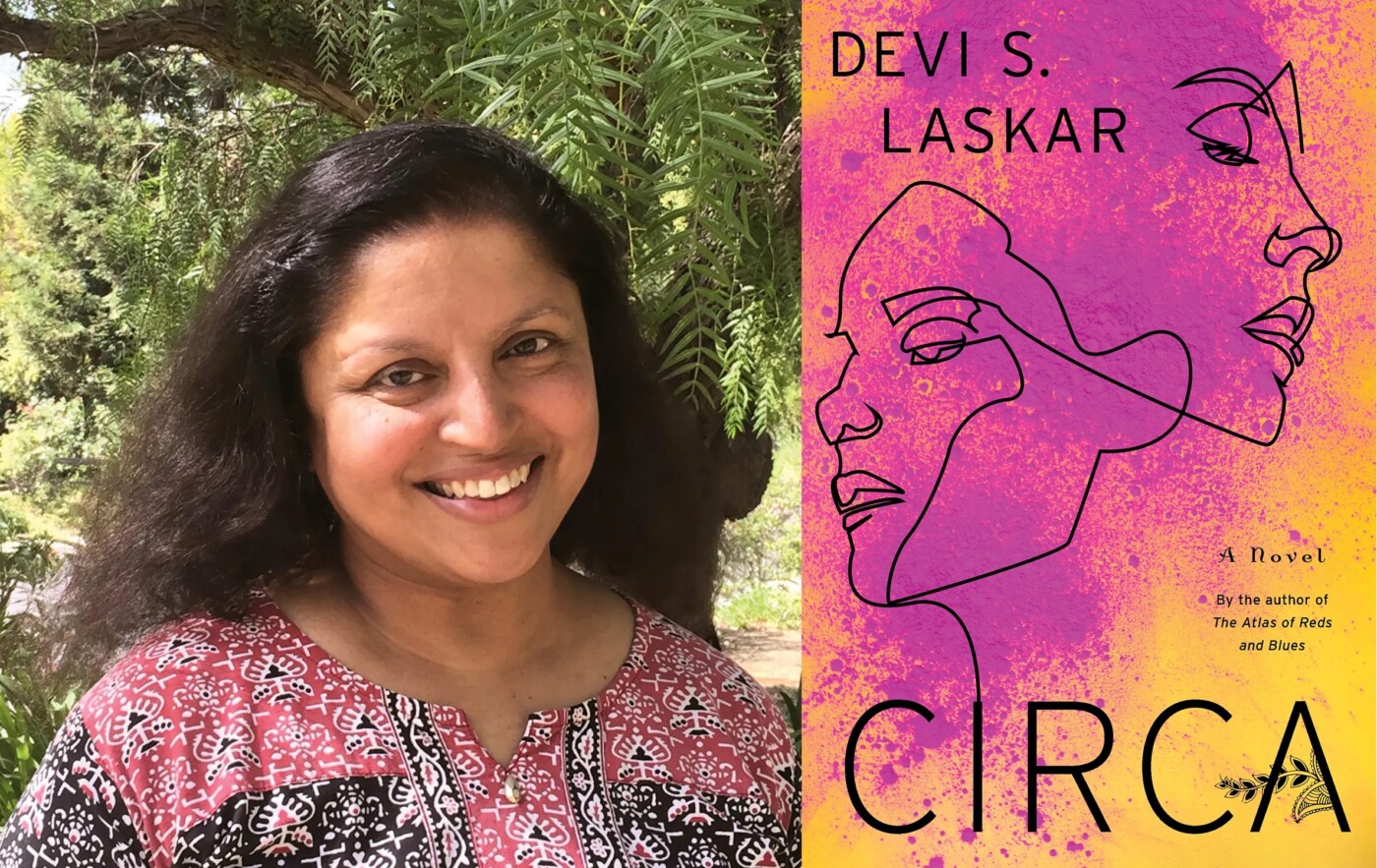

The title of Bay Area author Devi S. Laskar’s latest novel, “Circa,” published recently by Mariner Books is intriguing, from the get-go. The answer appears soon enough, however, when a reader is least expecting it, on page 38, in a chapter appropriately labeled “Exits.” Everything that happens in “Circa” may be marked, judged and justified using that portentous moment in the story arc.

The lack of numbered chapters, or chapter titles that hint at or tie up the developments in the story, is yet another distinguishing feature of this novel. More often than not, the chapter titles are obscure, one-word labels. Together, they compound the effect, adding to the growing feeling of despair as we plow through the happenings in the book.

Devi Laskar seems to have taken on a significant challenge in the way she narrates the story. She uses the second-person perspective, considered to be the most limiting point of view of all. It’s hard to sustain this point of view through a lengthy work owing to its limitations, but Laskar pulls it off with panache.

“Circa” narrates the family life of Heera Sanyal, an Indian American teen living in Raleigh, North Carolina, who arrived into the world on Halloween 1969, a few months after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. The parents are part of the lower-middle class, and if daily life is a struggle for this family, life in school is even more unpleasant for Heera, who only sees how different she is from everyone else at school.

Heera thus leads a hyphenated existence, caught between her “American” life at school and her “Indian” Bengali self at home, frustrated that her parents’ expectations for her do not align with life in their adoptive nation.

Set in the United States of the ’70s and the ’80s, the novel is also a story of young lives marred by the indignity and shame of poverty and racism. The two main characters carry the baggage of their adolescence into adulthood as well. “Circa” ends a little after the bomb blast at the World Trade Center in New York in 1993, a terrorist incident that left more than 1,000 people hurt.

Heera’s predicament in “Circa” is a classic trope from the Indian American immigrant story, and the author describes it masterfully with these two punchy sentences. “Your name represents a series of long unpronounceable expectations from a place across the globe that you never belonged to directly, but somehow the hooks are still there. Your name also represents what the good people of North Carolina want to see when they look at someone who looks like you, someone who looks so unlike them: A girl who is respectful and obedient, a girl who knows her place in the world, a girl who is invisible. In this way, the two worlds exist like an eternal syzygy.”

While Heera has just two friends at school, they understand her completely. Her parents, on the contrary, don’t comprehend her desires or approve of those friends or acquiesce to her list of wants. They even question the need for her to own a pair of athletic shoes and imagine that traditional Indian clothes are perfectly acceptable at school. Some people in school grimace at her lunch and mock her manner.

On one black day in their lives, life leaks out of Heera and her friend, Marco. An accident renders Heera, Marco and both their families inconsolable and broken. Almost every situation in “Circa” describes the anguish of the “othering” that is a feature of teenage years and, unfortunately, of civil society in the United States today.

Laskar’s craftsmanship is evident from the first page. Her words sparkle. Some are ominous, turgid with meaning.

“You learn in reverse order,” she writes in an opening line in a chapter titled “Girl, missing”; Krishna, Heera’s Bengali family friend, is missing, and almost everyone imagines her to be dead. We gather, however, in reverse order, the reason she left the security of home and family and how she is now alive and well, after all. On the day of a funeral that mars her life forever, Heera observes that the bird on the grass “is only a crow, a murder of one.” It’s a stunning turn of phrase that’s unexpected and, yet, so perfect for that grievous moment.

Recently, I emerged from a 10-day immersive read of the Neapolitan Novels by Elena Ferrante. There’s enough darkness in Ferrante’s work to fill a subterranean cave writhing with snakes. Perhaps it’s the first-person point of view that rendered the Ferrante series more real and more relatable for me, and perhaps that’s precisely why “Circa” — which is also a story about the vicissitudes of early childhood, adolescence and adulthood — did not drill deeply enough into the emotional state of all the characters in the novel even though they are richly deserving of empathy.

Early on in the book, I was thrown out of the work several times, and I persisted because Laskar clearly employed the second person for a reason. Yet, somehow, in my view, it detracted from the effectiveness of the story line. The second-person point of view is normally exploited for dramatic effect and, a few chapters in, I found myself taking part in an unexpected, horrific accident. For the reader, the experience is spine-chilling; I had to put the book away for some time. Strangely enough, this jarring incident in the book — one that felt so close to me — was also the point at which “Circa” began to engage me completely and all the stylistic impediments seemed to melt away and disperse from the pages.

Kalpana Mohan lives in Saratoga. She is the author of “Daddykins: A Memoir of My Father and I” (Bloomsbury, 2018) and “An English Made in India: How a Foreign Language Became Local” (Aleph, 2019).