In the high-poverty Oakland Unified School District, the disparities among schools of credentialed teachers are stark.

At Chabot Elementary in the hills above urban Oakland, with 23% low-income students, 93% of classes are taught by fully credentialed teachers; at Greenleaf Elementary, near the Oakland Coliseum, with 91% low-income students, fully credentialed teachers teach 47.5% of classes. In most middle schools and high schools, fewer than 60% of classes are taught by adequately certificated teachers, reflecting the ongoing difficulty in finding teachers credentialed to teach specific sciences like physics and math. At Castlemont High, fewer than one-quarter of teachers are assigned to classes they’re qualified to teach. Hiring decisions are made at the site level; the district does not place teachers at schools, it said.

Across OUSD, 57% of its teachers are assigned to classrooms they are credentialed to teach — the lowest of any district in California with more than 10,000 students and one of the lowest in the state. It is nearly a third lower than the state average, and the 27.4% of ineffective teachers, which include emergency and short-term permits and long-term substitutes, is nearly seven times the 4.1% statewide average.

The district blames its low rate of credentialed teachers on the churn of high turnover and has a plan to attack the problem.

In a news release, Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell acknowledged the low numbers of fully credentialed teachers but said the district is making teacher retention and recruitment of aspiring teachers, particularly people of color, a priority.

It has created Grow Your Own, with teacher residencies, an after-school pipeline and a teacher development program for middle school teachers.

It is providing mentoring and resources for all new teachers and, starting this year, will pay for new teachers’ credentialing fees and assessments. Earning a credential while initially teaching with an emergency permit is sometimes the only option for those who can’t afford to take a year off from work to become a teacher.

According to the OUSD, the high rate of teacher turnover — 22% in 2016-17 — dropped to the national average of 16% in 2019-20 and has remained constant since then. According to the district, 30% to 40% of the applicants for openings have emergency or out-of-state teaching permits. Out of the 491 teacher vacancies Oakland Unified posted, as of July 22, 109 remained unfilled, it said.

The impact of its strategies looks promising, the district said:

- 121 middle school teachers have received debt relief, tuition support and assistance with advanced degrees and credentials in exchange for their commitment to stay in Oakland for two to four years, depending on how much aid they receive.

- More than 100 special education teachers have received state funding for teacher prep, licensing fees, community college courses, education and student debt relief.

- 44 classified workers have received tuition support and mentoring to become credentialed teachers.

- 21 aspiring teachers earned their preliminary credentials in STEM and special education through the Oakland Teacher Residency program, in which an aspiring teacher trains full time in the classroom with an experienced, credentialed teacher. The district is partnering with the Alder Graduate School of Education. Teacher residents commit to staying four years with the district.

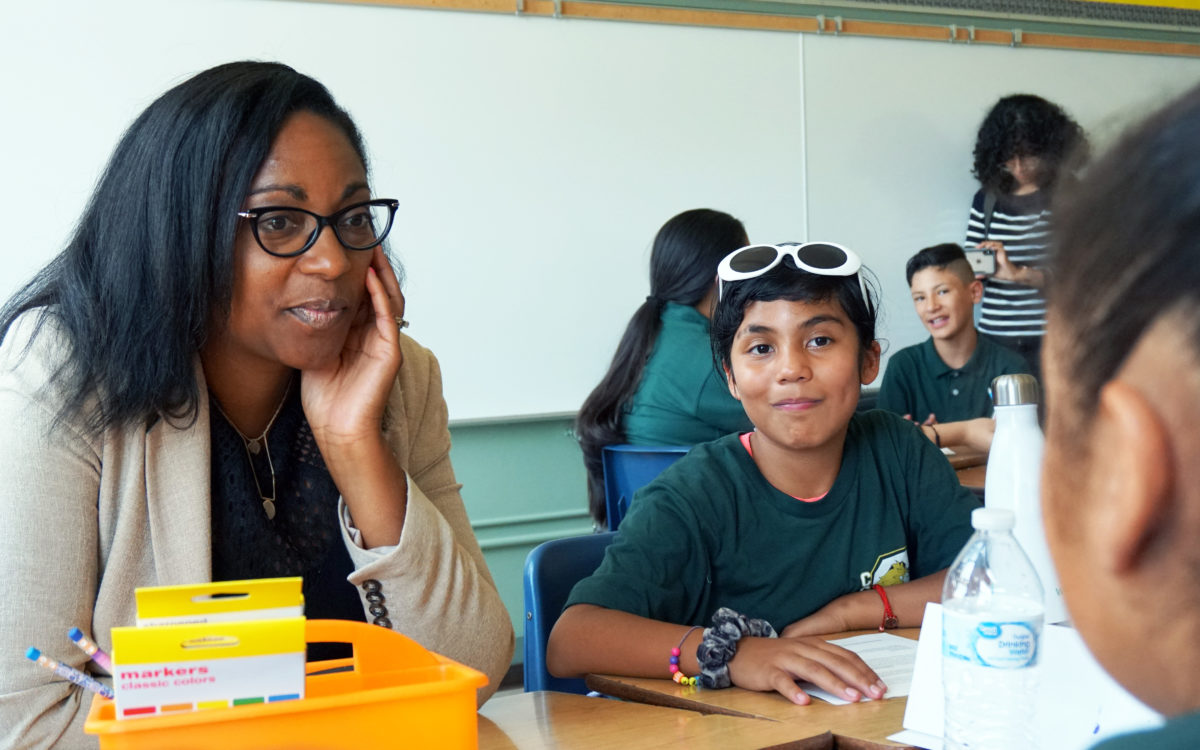

Oakland Unified has an enrollment of about 46,000 students, three-quarters of whom qualify as low-income. About half of the students are Latino, 20% Black, 10% white and 10% Asian. It employs about 3,000 teachers.

Oakland Unified also has above-average disparities in how those teachers are distributed across schools in the district. In schools with the highest-income children, 67% of educators are credentialed to teach the classes they are teaching, while 49% of teachers are qualified in schools with the most low-income students. Schools with the most low-income students also have double the percentage of intern teachers (4.4%) than schools with fewer low-income children (2%).

The reasons for the constant churn and difficulty finding teachers in Oakland with needed credentials depend on whom you ask.

Salary disparities among districts play a role in attracting teachers to some districts and pushing them away from others. The cost of housing in Oakland and the Bay Area is among the highest in the state, and Oakland’s salary scale, as of 2020-21, was among the lowest in Alameda County, from $50,600 for new teachers to $95,000 for the highest-paid veterans.

“Living wages continue to be an issue in Oakland,” said Keith Brown, president of the teachers union, the Oakland Education Association. “An experienced teacher can move to Hayward Unified and make $28,000 more overnight.”

In 2019, the union went on strike for seven days, demanding higher pay and improved conditions. Teachers settled for an 11% raise over four years. It conducted a one-day strike this year to oppose the district’s plan to close seven schools. Tense relations with the district’s unions, declining enrollment — a loss of 17,000 students over 20 years — and financial difficulties, which have dogged Oakland since the state provided a $100 million loan in 2003, have fostered strife and instability. When she was appointed superintendent in 2017, Johnson-Trammell, who grew up in Oakland and attended Oakland schools, became the sixth superintendent in nine years.

In a biting letter of resignation on her blog in May upon resigning from the school board, Shanthi Gonzales spread the blame. She cited the teachers union’s “refusal to engage on the issue of school quality,” general incivility in the district in handling disagreements and an easily distracted school board’s failure to focus on improving academics.

Arun Ramanathan, the CEO of Pivot Learning, a national school improvement nonprofit based in Oakland, agreed with Gonzales’ last point. Oakland is the home of an abundance of education nonprofits and foundations ready to fund new ideas. But the district’s focus must be on three things, he said: leadership, teaching and learning. “Ongoing instability bleeds into other areas, so the district turns to another initiative, whether social-emotional learning or community schools,” he said. “Oakland has one of the longest strategic plans, but it’s not focusing on the right stuff.”

OUSD should be constantly monitoring the number and distribution of long-term subs and the level of teacher absences, he said, as well as tracking, in a competitive market, the length of time between job interviews and job offers.

Gary Yee, the president of the district’s school board, said in a statement that although the issues of a teacher shortage and under-preparation in Oakland schools are not new or simple, the district’s “commitment to hiring well-trained teachers with strong academic preparation and a deep local and cultural competency has never been stronger or more focused.”

“Using the term ‘ineffective’ to label those who have not received state certification suggests a biased use of language. Privileging people who have the finances, time and opportunity to complete a credential before they start formal teaching in an Oakland Unified classroom blocks those who need to take a different path,” he said. “Even a cursory review of the Talent Divisionweb page will reveal the multiple paths to becoming and growing as a professionally effective educator. With this support, all children and educators — regardless of their background or circumstances — will have the opportunity to reach their highest potential. I believe Oakland is moving in that direction.”