The same wastewater surveillance techniques that have emerged as a critical tool in early detection of COVID-19 outbreaks are being adapted for use in monitoring the startling spread of monkeypox across the San Francisco Bay Area and some other U.S. communities.

Before the COVID pandemic, wastewater sludge was thought to hold promise as an early indicator of community health threats, in part because people can excrete genetic evidence of infectious diseases in their feces, often before they develop symptoms of illness. Israel has for decades monitored wastewater for polio. But before COVID, such risk monitoring in the U.S. was limited largely to academic pursuits.

With the onset of COVID, a research collaboration that involves scientists at Stanford University, the University of Michigan, and Emory University pioneered efforts to recalibrate the surveillance techniques for detection of the COVID-19 virus, marking the first time that wastewater has been used to track a respiratory disease.

That same research team, the Sewer Coronavirus Alert Network, or SCAN, is now a leader in expanding wastewater monitoring to detect monkeypox, a once-obscure virus endemic to remote regions of Africa that in a matter of months has infected more than 26,000 people globally and more than 7,000 across the U.S. The Biden administration last week declared the monkeypox outbreak a public health emergency, following similar decisions by health officials in California, Illinois, and New York.

And SCAN’s scientists envision a future in which wastewater sludge serves as a reservoir for tracking a slew of menacing public health concerns. “We’re looking at a whole range of things that we might be able to test for,” said Marlene Wolfe, an assistant professor of environmental health at Emory.

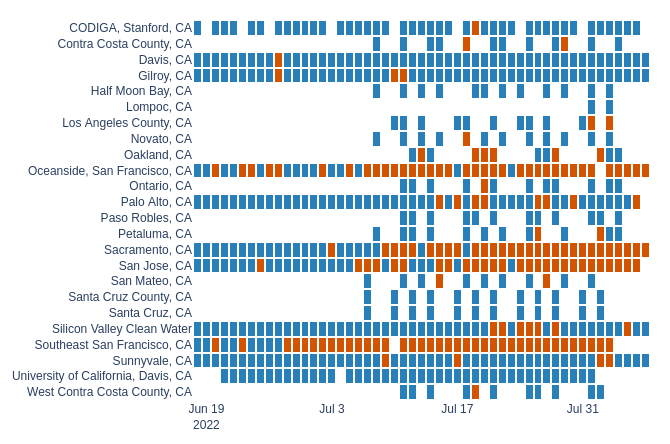

Since expanding its surveillance in mid-June, the SCAN team has detected monkeypox in several of the 11 Northern California sewersheds it is monitoring, including Palo Alto, San Jose, Gilroy, Sacramento, and two locations in San Francisco. Funded by grants from the National Science Foundation and the CDC Foundation, SCAN is doing similar monitoring in Colorado, Georgia, Michigan, and four other states and wants to scale up to 300 U.S. sites.

It is one of a growing number of sewage surveillance projects across the U.S. run jointly by universities, public health agencies, and utilities departments that are feeding COVID findings to state and federal agencies. How many of those networks have expanded their search to monkeypox is unclear. SCAN sites in California, Georgia, Michigan, and Texas and a research team in Nevada are among the few that have reported sludge samples that tested positive for the monkeypox virus.

As with COVID, data on monkeypox can be used to compare trends across regions, but there are limits to what this kind of monitoring can accomplish. Wastewater monitoring doesn’t pinpoint who is infected; it reveals only the presence of a virus in a given area. And it takes a specialist to analyze the samples. Researchers consider wastewater surveillance a complement to other public health tools, not a replacement.

“We’re still really on the front end in terms of discovering the potential here,” said Heather Bischel, an assistant professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of California-Davis, which included wastewater monitoring as part of its Healthy Davis Together COVID testing program for the campus and surrounding community. “But what we’ve seen already shows that this type of monitoring is adaptable to other public health threats.”

Some U.S. communities were sampling sewage before the pandemic to figure out what kinds of opioids residents were using. More recently, along with COVID and monkeypox, the technology has shown promise for monitoring flu and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is planning pilot studies to see whether sewage can reveal trends in antibiotic-resistant infections, foodborne illnesses, and candida auris, a fungal infection.

Much of the wastewater testing that ramped up during the pandemic’s first year was done in concert with universities or county offices and reliant on funding provided through federal COVID relief legislation. On Bischel’s campus, those funds were combined with university donor money to put together a comprehensive testing and treatment program for the school and the city of Davis that included wastewater surveillance. The sewage testing is ongoing under a separate grant.

Currently, the CDC is reporting only COVID results on its national wastewater surveillance system, a reflection of the limited number of sewersheds that so far are testing for monkeypox.

The global spread of monkeypox was first detected in the United Kingdom in May and prompted conjecture that this virus, too, might shed into wastewater, either through feces or when an infected person with an open sore takes a shower. Sewersheds in areas with infected people might then “light up” with evidence of the disease — if the wastewater testing could pinpoint it.

“It did light up,” said Brad Pollock, who chairs public health sciences at UC Davis Health.

“It acts as a warning system, and you don’t have to persuade people to take individual tests in order to use the information; it’s collected passively, so you get a more broad community look.”

The virus is thought to be spreading primarily through intimate skin-to-skin contact and exposure to symptomatic lesions, although researchers are exploring other potential means of transmission. For now, the U.S. outbreak is concentrated largely in gay communities among men who have sex with men.

The discovery of monkeypox in San Francisco’s wastewater system in June, the first such finding in the nation, set off alarms in a city with a thriving LGBTQ+ population. On July 28, San Francisco declared monkeypox a public health emergency, urging the federal government to step up its distribution of vaccines.

For its Northern California surveillance, SCAN partners with local health officials and universities to collect samples and then sends them to Verily Life Sciences — a health tech company owned by Google’s parent company, Alphabet — for analysis. In the Atlanta area, SCAN is working with Emory and Fulton County health officials.

Not all public health agencies are moving as fast. A wastewater monitoring plan for the virus is only now being put together in Los Angeles County, which had confirmed more than 300 cases of monkeypox by the end of July.

And though California is collecting monkeypox data from its surveillance partners, it’s not available for all regions, underscoring that wastewater monitoring for viruses is still an emerging methodology.

“With every new thing that we add to the testing platform, we are learning things,” said SCAN’s Wolfe. “The pandemic really cracked open our imagination for a tool that already existed but that hadn’t been developed to its full capacity. That’s changing now.”

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.