For years, the idea of establishing supervised drug injection sites has been a long-standing goal for some progressive California leaders looking to address the burgeoning overdose crisis. But that goal continues to be elusive as Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill that would set up such sites in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Oakland.

Senate Bill 57 would have authorized these overdose prevention pilot programs through Jan. 1, 2028.

“I have long supported the cutting edge of harm reduction strategies. However, I am acutely concerned about the operations of safe injection sites without strong, engaged local leadership and well-documented, vetted, and thoughtful operational and sustainability plans,” Newsom said in his veto message Monday, noting his concern for unintended consequences.

“Worsening drug consumption challenges in these areas is not a risk we can take,” he wrote.

Gov. Jerry Brown also rejected similar legislation in 2018, but supporters of the bill were hopeful Newsom would sign this one after he said he was open to the idea during his campaign for governor.

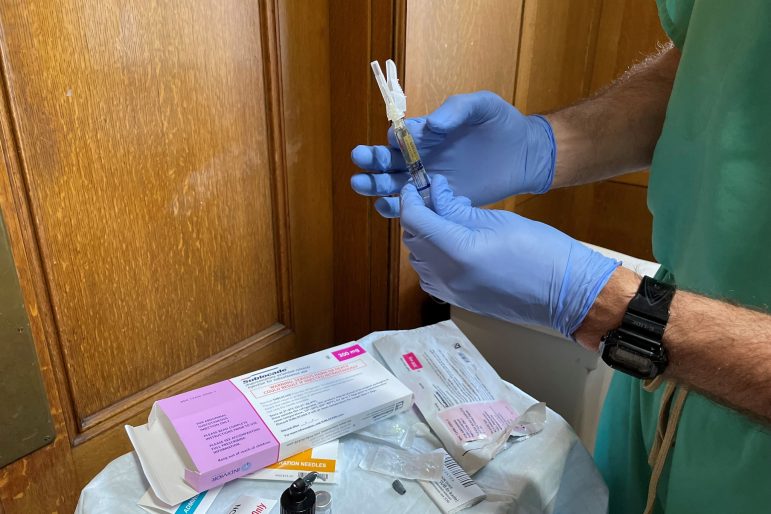

The goal of these programs, supporters said, is to provide drug users a safe, hygienic space where they can get clean needles and administer their own drugs under the supervision of trained staff. Staff members would monitor users and be ready to administer overdose reversal medications if needed, which could ultimately save lives. Medical groups in support of these programs have pointed out injection sites could also help reduce the risk of Hepatitis C and HIV infections associated with intravenous drug use.

Sen. Scott Wiener, the San Francisco Democrat who authored the bill, called Newsom’s veto tragic.

“By rejecting a proven and extensively studied strategy to save lives and get people into treatment, this veto sends a powerful negative message that California is not committed to harm reduction,” Wiener said in a statement.

“For eight years, a broad coalition has worked to pass this life-saving legislation. Each year this legislation is delayed, more people die of drug overdoses,” he added.

Sponsors of the bill called Newsom’s decision a political move from a blue state governor whose recent actions have fueled speculation that he could be planning a presidential bid.

“We are outraged and frustrated by the political move Governor Newsom has made in vetoing SB 57,” Tyler TerMeer, CEO of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, said in a statement.

“Governor Newsom is turning his back on his constituents and on the overdose crisis affecting every corner of our state and our nation. We are losing our friends, our family members, and our loved ones. We need our leaders in government to step up and implement solutions that will save lives.”

Part of Newsom’s reasoning behind the veto seemed to be his concern for the “unlimited number” of sites that could have popped up as a result of the bill. Supporters of the bill rejected that argument.

“While Newsom plays on the fears that an ‘unlimited’ number of Overdose Prevention Programs could have been opened, this would have been a limited pilot program that was only for five years and three jurisdictions, with an extremely thorough evaluation process,” said Jeannette Zanipatin, state director at the Drug Policy Alliance, another bill sponsor.

The bill came with no dollars attached, meaning that each county or city interested in setting up a site would have to find its own source of funding to operate the sites. Each site could cost a couple of million of dollars a year to operate.

San Francisco has been considering this idea for almost a decade, and had the bill passed, it would likely have been the first ready to launch a program in early 2023, Zanipatin said.

Last year, New York City became the first to establish supervised injection sites in the U.S. Cities in other countries have operated such centers for years, including Vancouver, Mexicali and Barcelona. The Vancouver site is often referenced as a model — with about 1,700 individuals using it each month, the center is credited with reducing overdose deaths in its neighborhood and city. Switzerland was the first country to open a supervised injection site in 1986.

Following Newsom’s veto, San Francisco City Attorney David Chiu told the San Francisco Chronicle that he supported moving forward with plans for a safe injection site regardless of state support, the way New York City had. But a state law could have granted more legal and political cover to whichever community organization ran the site, Zanipatin said.

Among those urging the governor to veto the bill was the Senate Republican Caucus. “Fueling the drug epidemic with drug dens and needle supplies is like pouring gasoline on a forest fire. It merely worsens the problem,” the caucus wrote in an Aug. 1 letter to Newsom.

Law enforcement organizations also stated their opposition to the bill, saying it sent the wrong message to the public and failed to address addiction at its root.

Following Newsom’s veto, the Senate Republicans released a statement in which they took credit for “securing” a veto. “People struggling with addiction need help, not a legal place to shoot up,” said Sen. Scott Wilk, a Lancaster Republican.

The overdose crisis has become one of the most pressing public health issues, with deaths and emergency room visits spiking in recent years, in large part due to the infiltration of the synthetic opioid fentanyl. Overdose deaths from fentanyl jumped from 1,603 in 2019 to 3,946 in 2020, and then to 5,722 in 2021, according to the California Opioid Overdose Surveillance Dashboard.

California’s second swing at this policy came as the Biden administration embraces “harm reduction” strategies — which focus on keeping drug users alive and safe rather than punishing them. Needle exchange programs and programs that distribute the overdose reversal drug naloxone are some examples.

Wiener and supporters of the bill said supervised injection sites would not have solved the overdose crisis. Rather, the goal was to prevent deaths.

Opponents had also raised concerns about the bill not providing a “cognizable strategy for figuring out how to get the addict to the injection site,” John Lovell, a lobbyist with the California Narcotic Officers’ Association, said during a hearing earlier this month. “What injection sites do is there is a magnet effect so that people come into the area,” but that doesn’t mean they will actually go inside the facility, he said.

Laura Thomas, director of HIV and harm reduction policy at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, said she doesn’t think getting people into these centers would have been a challenge. “Overwhelmingly, people would prefer to use in a clean space. No one wants to be using drugs on the sidewalk. If we give people a better option they will use it,” she said.

An often-referenced survey of 602 injection drug users in San Francisco showed that 85% would use a supervised injection site. About 75% of them said they would use it at least three days per week.

The idea, according to supporters, is to build trust with people who come in, prompting them to spread the word and eventually link people to treatment when they are ready.