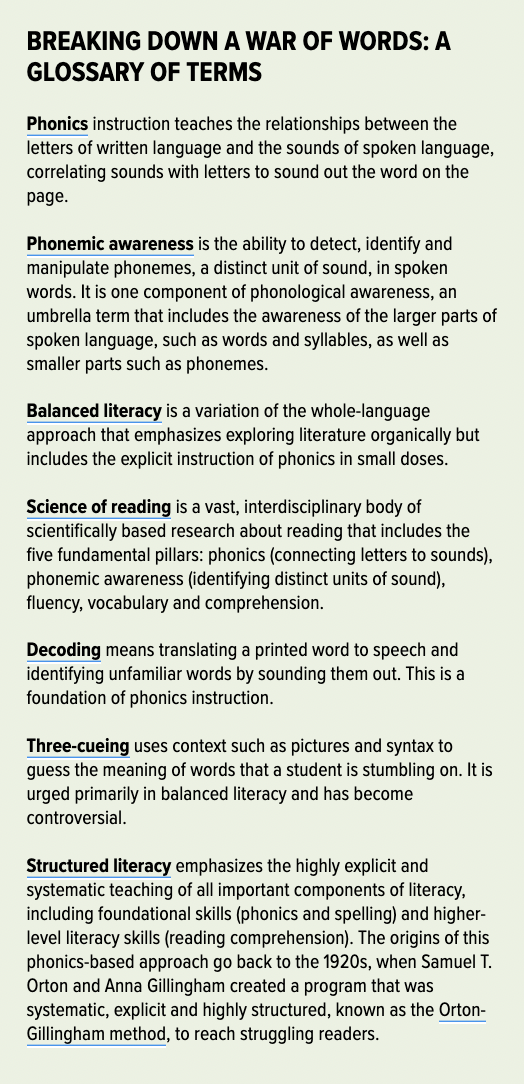

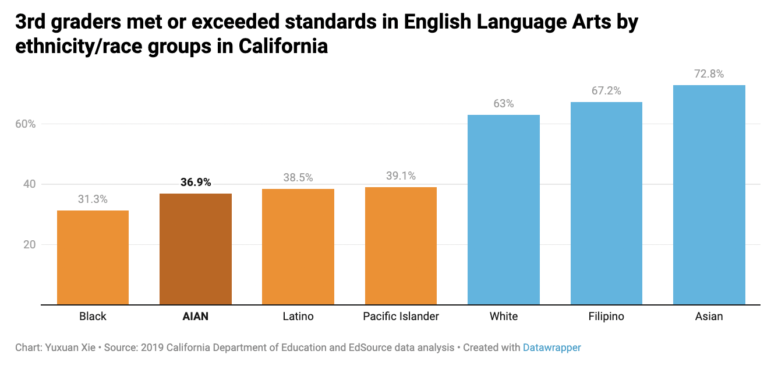

California fourth graders trail the nation in reading, and half of its third graders, including two-thirds of Black students and 61% of Latino students, do not read at grade level.

Yet, California is not among the states — including Mississippi, North Carolina, Florida, Connecticut, Colorado, Virginia and New York City — that have adopted comprehensive literacy plans to ensure that all children can read by third grade. And California has not set a timeline or given any indication it intends to create such a plan.

“The problem is we’re still at the first stage of acknowledging there’s a problem,” said Todd Collins, a Palo Alto school board member and an organizer of the California Reading Coalition, a literacy advocacy group.

“We’re just not seeing that same level of involvement and intensity that other states have had,” said Linda Diamond, a retired executive of a California-based reading improvement firm who tracks literacy legislation and teacher preparation programs across the nation.

In 2017, California was the first state to be sued on the grounds that it had denied children’s civil right to literacy under the state constitution. After initially fighting the lawsuit, the state settled the case in February 2020. It agreed to spend $50 million on a three-year reading improvement program for 75 of the lowest performing schools, where at some schools fewer than 10% of children were reading at grade level.

And yet in 800 schools, 75% of students failed to read at grade level, and the state has not recognized their plight beyond those in the settlement, Mark Rosenbaum, an attorney who represented the families in the Ella T. v. the State of California case, said during an EdSource roundtable in April.

The state’s largely hands-off early literacy policy, said Rosenbaum, is “mainly talk, barely walk.”

Meanwhile, galvanized by the success of Mississippi, the nation’s poorest state, many states have overhauled reading instruction in the early grades. Since adopting a package of reading reforms in 2013, Mississippi’s reading scores rose steeply on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which all states take every two years. In 2019, it was the only state to see a rise in scores.

At the same time, articles and podcasts by American Public Media journalist Emily Hanford drew widespread attention to commonly used but ineffective reading methods and to research supporting phonics and other evidence-based techniques collectively called the science of reading.

California has taken some promising steps to adopt elements of the science of reading, including a plan to place reading coaches in some high-poverty schools, to better prepare new elementary school teachers to teach reading and to create a multilingual screening tool to recognize reading challenges in kindergarten through second grade.

Literacy experts say these steps, while useful, will have limited impact unless California and other states take a more muscular and cohesive approach to early reading. Effective, focused instruction in decoding skills, such as phonics, in kindergarten and first grade, as well as attention to vocabulary acquisition and reading comprehension, should be part of that effort. Teachers and coaches must be trained in the science of reading; textbooks should support it.

Alberto Carvalho agrees. Before becoming superintendent of Los Angeles Unified this year, he led Miami-Dade County Public Schools. In 2019, the nation’s fourth-largest school district was the top performer in fourth grade reading and math of the 27 urban districts that every two years take the National Assessment of Educational Program. Los Angeles Unified was fifth from the bottom.

Carvalho’s advice to the state would be the same as for LAUSD, he said: Insist on a rigorous and relevant curriculum; follow the science of reading instruction, “which has proven to be most effective with young learners”; and ensure that graduates of colleges of education are experts in the cognitive development of students who can produce “not only proficient readers, but also lovers of reading.”

All of this, literacy experts say, demands a cohesive approach. Replacing a part or two in a complex system of gears and levers won’t make the machine run better.

“There’s no silver bullet in this; you can’t just change one thing and expect outcomes to change for kids,” said Emily Solari, a professor of reading education at the University of Virginia, who provided a framework for drafters of the new Virginia law.

California’s education leaders acknowledge that the state needs to do more to improve early literacy.

In a wide-ranging interview with EdSource, Linda Darling-Hammond, State Board of Education president and TK-12 adviser to Gov. Gavin Newsom, said the state is rethinking how it can improve early literacy. Parents and teachers can expect to see more instructional guidance, teacher training and expert coaches.

What they won’t see is the state requiring a specific curriculum or teaching strategy.

California’s laws ensuring local control over many facets of education will constrain actions compared with other states, she said. “But even where there’s local control, the state can lean in — on guidance, on incentives and on resources.” Darling-Hammond detailed her thinking in recent commentaries published by EdSource.

Select California districts — Chula Vista, Clovis, Gridley, Hawthorne, Long Beach, San Diego and Sanger — offer examples of what others can do, she added.

Mississippi directed its money into literacy coaches and intervention specialists in high-needs schools, Darling-Hammond said. “That’s probably the right initial role for the state here, too.”

In October 2021, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond named a Statewide Literacy Task Force, with the goal of achieving universal literacy in third grade by 2026. Napa County Superintendent Barbara Nemko, one of seven co-chairs, said she hoped the group would write “a report that will give teachers the tools they need to teach reading.”

But so far, the task force has agreed only on noncontroversial things, like expanding students’ access to library cards and providing English learners with more books in their native languages. It’s not clear if the task force will take on the bigger issues of instruction: “What do we have to teach? When do we have to teach it and in what order?” she said.

Whatever directions they choose, state leaders will face the apprehension of veteran teachers and the English language learner community. Teachers with memories of Reading First, a federal initiative in the early 2000s, will worry that the next round of phonics-grounded curricula will be just as regimented. Advocates of structured literacy, which emphasizes reading comprehension as well as decoding skills, say they too don’t favor a repeat of the past.

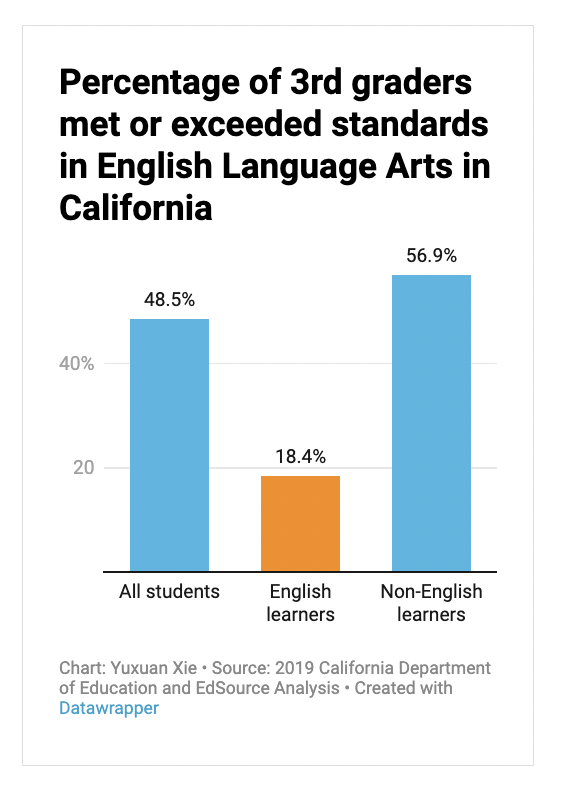

Advocates of English learners, who comprise one 1 in 4 first graders in California, say they will oppose reading curricula that don’t meet their children’s needs. They raised concerns that a phonics-focused curriculum will exclude other critical skills: developing oral language skills, vocabulary and cross-language connections.

What California isn’t doing

States with comprehensive literacy plans generally have common components. They require the state to oversee or monitor literacy efforts. They include providing common standards for teacher preparation programs and professional development of classroom teachers; hiring or setting requirements for literacy coaches; vetting or sometimes choosing curricula for districts; mandating reporting to parents and the community on the state of literacy.

California’s minimalist approach to early literacy has left every district mostly on its own, creating confusion, uncertainty and sometimes conflicts at the local level, undermining children’s ability to learn to read, according to educators, literacy experts and district and state leaders interviewed for this article.

California does have a policy on the science of reading, which encourages explicit instruction in foundational skills in the early grades. But the policy was poorly promoted and is rarely mentioned or used.

It is tucked in a voluminous document, the English Language Arts/English Language Development Framework for California Public Schools, covering K-12. The State Board of Education adopted it in 2014, and the state summed it up in a 23-page “white paper” on foundational skills. As with other states’ academic frameworks, they consist of recommendations, not requirements.

“There wasn’t a coherent rollout,” Diamond said. “The framework was distributed to districts and county offices, but not through the ranks. So many teachers never really read it. Then, two years later, the state approved a list of textbooks. By then teachers were pulling things off the internet.”

Darling-Hammond acknowledged it is important to reacquaint districts with what is in the frameworks.

Contrary to states with effective approaches, California does not know how well its K-2 children are doing in reading. The first time that the state measures children’s reading skills is in the spring of third grade, with the Smarter Balanced English language arts scores, and those results aren’t public until the students are in fourth grade.

The Department of Education does not collect school or district data on periodic diagnostic assessments, which inform teachers of students’ progress and weaknesses. It doesn’t ask districts to tell them what assessments and textbooks they are using. It doesn’t know if students who need intensive reading help are getting it.

The State Board of Education does not require districts to report on early literacy in their Local Control and Accountability Plans, the document in which districts set three-year academic goals and are held accountable for them. It does not require districts to engage parents on their children’s reading or report to them on how well the district is doing in achieving literacy.

“When the required data begins in grade three, the resources of a school tend to be targeted towards grade three with a focus on intervention – instead of on high-quality instruction for all students in grades kindergarten and first grade,” said Margaret Goldberg, a literacy coach in West Contra Costa Unified who is instructing coaches from the schools receiving help in the Ella T lawsuit.

Little help with curriculum and instruction

After reviewing scientific research, the National Reading Panel concluded in 2000 that the most effective method to teach children encompasses five pillars — phonemic awareness (the ability to identify individual sounds); phonics (the ability to identify written letters from spoken language); fluency (the ability to read quickly and accurately); vocabulary; and comprehension. But the battle between advocates of phonics-based structured literacy, and those of balanced literacy, a hybrid that de-emphasizes phonics and explicit instruction, continues in classrooms throughout California and in the textbooks they use. As EdSource has reported, this philosophical tug of war persists despite exhaustive research suggesting most children must be explicitly taught how to connect sounds with letters.

According to a survey by the California Reading Coalition, 70% of districts use two textbooks, Reading Wonders by McGraw-Hill, and Benchmark Advance by Benchmark Education. And those “big-box” publications send “mixed messages,” Goldberg said. They include units on phonics and decodable texts as well as an abundance of material on balanced literacy that publisher focus groups say the market demands.

As a result, districts must piece together materials from multiple sources without guidance from the state. “At my school, we use one program for foundational skills instruction and another program for language comprehension instruction,” Goldberg added.

Collins said that the best curricula for structured literacy aren’t on California’s list of materials. Districts aren’t obligated to buy from the state’s list, and many don’t. Last year, Los Angeles Unified added Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA), a structured literacy elementary school curriculum with a high rating on EdReports, which evaluates school materials. The district said it chose CKLA because it “provides explicit, systematic and cumulative foundational skills instruction.”

The California Department of Education leads the textbook and materials adoption process — a laborious undertaking involving dozens of teachers. The state board adopted the current list in 2015, and the next approval is five years away.

“It would help if the state came out with more information,” said David Schrag, director of elementary education for Pleasanton Unified, a 14,000-student district in the Bay Area where 16% of students are low-income. “Rarely does the latest information come from the state.”

Arun Ramanathan, the CEO of Pivot Learning, a national school improvement nonprofit based in Oakland, said districts should seize the rare opportunity to upgrade materials.

“Most of the curricula in California classrooms is low quality and years out of date,” he said. “It is irresponsible for districts to wait for the state to complete its endless adoption process when districts can use their federal Covid relief funding to buy up-to-date math and English materials and professional development for their teachers right now.”

Collins said state leaders could encourage districts to do so but haven’t.

Not only new teachers but all teachers need good instruction grounded in the science of reading, but many haven’t had it, experts said.

“For teachers who learned a balanced literacy program, it’s a really tough shift,” said Schrag, referring to the blended instruction that includes literature-based learning and phonics. Imagine teachers who believe they have been teaching reading successfully, he said. “‘You’re telling me I have to learn entirely new fundamentals of phonemic awareness, phonology with academic language.’ A lot of stuff they’re not used to.”

North Carolina is paying for all teachers to take LETRS, a widely used but intensive, two-week immersion in science of reading instruction.

All of Pleasanton’s TK-fifth grade teachers will take the training over four to five years. Schrag wishes California would encourage it. “It’s really important that we agree as a state that this is something you should do. So you don’t have to fight (over it),” he said.

Added Goldberg, “The state is reluctant to tell schools what evidence-based instruction is, how you look for it in a curriculum, making sure that there is an approved list of professional development on the materials, and funds for the materials themselves.”

New standards for new teachers

One area where California has taken a significant step is in preparing future teachers.

The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, following a 2021 law, is revising standards for reading instruction for teacher preparation programs. The commission is expected to adopt them this fall.

“The law is not ambiguous about what needs to be included in teacher preparation,” said Executive Director Mary Sandy. “It certainly includes a focus on the science of reading and the foundational skills.”

Starting in 2026, candidates for a TK-to-fifth credential or a multisubject credential for teaching in elementary and middle schools must pass a new performance assessment to demonstrate knowledge of the standards.

Not a funding priority

If learning to read by third grade is a fundamental right and the gateway to success, the Legislature hasn’t prioritized it. This year’s massive $110 billion TK-12 funding dedicates little for early literacy but districts can decide to spend some of the extra money they are getting on early literacy staffing, books and training. While the Legislature added $1 billion for community schools, on top of $3 billion last year, and $4 billion for after-school programs, it cut in half the $500 million Newsom sought for reading coaches.

The $250 million that did pass for reading coaches is enough to staff only schools with at least a 97% poverty rate — 440 of the state’s 10,500 schools. And budget language (see SEC. 137) does not require that coaches use evidence-based methods or the science of reading.

At the urging of Newsom, who has been candid about his struggles with dyslexia, the state appropriated $18 million to the University of California San Francisco to create a screening tool in multiple languages to detect reading difficulties, including possible dyslexia. However, the bill to require an annual administration for K-to-3 students — urged by parents of dyslexic children — stalled this year. Advocates of English learners and the California Teachers Association opposed it. They said they were concerned English learners would be over-identified as dyslexic.

Darling-Hammond said she is open to using incentive grants as an alternative to mandates to fund early literacy initiatives. The ambitious community schools initiative, which Darling-Hammond championed, lists lengthy requirements to participate and includes state monitoring. But, with budget forecasters projecting flat revenues – less, if there’s a recession — a once-in-a-generation funding opportunity may vanish.

“We’ve missed the window,” Collins said.

Concerns for English learners

Kymyona Burk, who directed Mississippi’s literacy reforms, starting in 2013, and now advises state leaders as policy director for early literacy at the Foundation for Excellence in Education, said she works with states with local control. They at least should educate school boards in the science of reading before they make key decisions.

But states also could pass laws telling districts, “you have to adopt curriculum and professional development grounded in the science of reading and coaches supporting teachers using the science of reading.”

Darling-Hammond said California classrooms are complex. How reading is taught in a district with a majority of Spanish speakers in bilingual classrooms will differ in a district, like San Francisco, where 22 languages are spoken, or districts with mostly English speakers. Providing guidance, not mandating instruction, is the state’s role, she said.

There’s not a lot of disagreement among researchers on how children learn to read, she said. “The disagreement surfaces when you start to talk about what’s happening in particular districts under the banner of science of reading,” she said.

There’s the rub. English learner advocates worry the pendulum will swing too far to phonics.

“Think about our young kids who come to kindergarten who have spoken English for five years before they step into the classroom versus kids who don’t know one word of English,” said Shelly Spiegel Coleman, strategic adviser for Californians Together, which advocates for English learners. “You start dissecting English. Breaking up those sounds and trying to put them together means nothing for a kid who doesn’t know a word of English. It’s a game, it’s not literacy.”

Spiegel-Coleman and Martha Hernandez, Californians Together’s executive director, said they support explicit instruction in foundational skills. “It’s a matter of dosage and duration. We don’t want the entire literacy block dedicated to foundational skills.”

Researchers and national representatives of proponents of the science of reading and of the multi-language interests, including some California leaders, have met quietly to try to resolve their differences. Darling-Hammond has observed the conversations.

Their fourth meeting is coming up. “Perhaps there might be a joint statement down the line on the things that we agree to do. We’ll have to see,” Hernandez said.

A lot is riding on their success.

The ability to read by third grade is critical. When children needing intensive help become proficient in reading in first and second grade, Goldberg said, “their attitude towards school is different; their engagement in school is different, their feelings of whether they belong there is different.”

“We can change the trajectory of that child’s life — if we have the resources in place.”