Since Nadhi Thekkek and Rupy Tut presented “Broken Seeds Still Grow” in its earliest incarnation, they have examined and overhauled it several times based on the responses to the multimedia production, which premiered at Flight Deck in Oakland in 2017. Now, Bay Area audiences have the opportunity to see the latest version 3 p.m. Saturday at Livermore’s Bankhead Theater.

“Broken Seeds Still Grow” tells stories about the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent into two separate nations — of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan — which immediately followed India’s independence from British rule and was accompanied by one of the largest mass migrations in human history. Overnight, approximately 7 million Hindus and Sikhs and 7 million Muslims found themselves migrating to the “other” country. Believing they would return home, many families left their valuables behind before they packed up their essentials and began the trek to India or West or East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Many never made it to their new homes, as they became victims during the horrific violence that ensued.

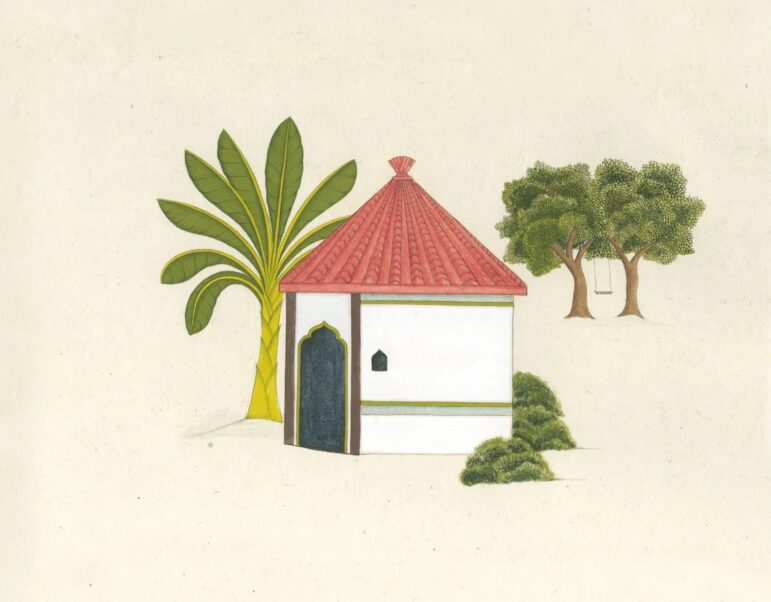

The show harnesses the narrative powers of the classical Indian arts of Bharatanatyam dance, Indian painting, calligraphy and spoken word to examine the Partition, and its significance across the South Asian diaspora. But “Broken Seeds Still Grow’s” examination of the traumatic aftermath of that cleavage on the human psyche — displacement, separation, violence, angst and loss — makes for a story that will resonate with anyone anywhere. In the five years since the first production, there have been many more displacements of people in the world than we could have imagined possible: the U.S. border crisis, Burma, Afghanistan, Ukraine.

The two artistes behind the project are young Indian Americans with diverse backgrounds. Nadhi Thekkek is a second-generation immigrant engineer who directs Nava Dance Theatre, a Bharatanatyam dance company based in San Francisco. The child of parents originally from south India’s Kerala, she grew up removed from the political upheavals common to the north of India. Oakland-based Rupy C. Tut, however, grew up hearing scores of personal stories about Partition from her grandparents. Tut came of age in India’s Punjab and moved to the U.S. as a high school freshman, thus retaining her ties to her Punjabi Sikh background.

Nadhi’s own inspiration for the show grew from a 1947 Partition Archive event held in the Bay Area, “Voices of Partition,” in which she heard witness statements and listened to stories of displacement and communal violence.

She realized that the deepening divisions and hateful rhetoric in America that paved the way for the Trump presidency were not different from the divisive tactics the British employed to drive a wedge between Hindus and Muslims in India: “That got me really interested in learning more and making that connection between what is considered history and what is very present.”

Among the many works of art that grace “Broken Seeds Still Grow” is a painting by Tut that depicts a woman carrying an enormous weight on her back. Thekkek found it deeply moving because it brought into relief the burdens, both visible and invisible, that women often carry. For Tut, it was also intensely personal. It gave voice to the sadness that shrouded her family’s past.

Tut’s grandmother was among the many mothers who had an infant die during the long trek toward their new home in 1947. Tut says that she never understood why her nani (maternal grandmother) opted to remain silent about that period of her life. As an adult, she began to understand a lot of things about her. “Her legs were always weak,” Tut says, acknowledging that her nani’s sorrow is now a permanent weight inside herself, too. That inheritance of grief, above all, is a fact of life for families that have endured the tragedies of displacement.

“Broken Seeds Still Grow” is also a story about the positive spirit of human beings and is also a tribute to the stories of ancestors who faced displacement either through Partition or immigration, but continued to be resilient in thriving in the new place they called home. Both Thekkek and Tut have been amazed at the power of their storytelling collaboration. Thekkek says she feels that Tut’s narration onstage is sensitive to her as a dancer and finds herself improvising because she knows that Tut understands her completely. It’s a harmonious effort that, many times, has reduced them both to tears onstage.

Sometimes their show has raked up memories that lay buried in people.

In their production, Thekkek’s team enacted the pathos of a family caught in the throes of leaving their home for good; in the choreography, the act of burial of some jewelry is shown for a fleeting moment. During the discussion that followed one of their shows, a member of the audience revealed that her family did exactly that — bury their family treasures in their home — hoping they would go back when the times were good. Unfortunately, they never could.

“At the end of the story, we were both in tears,” Thekkek says. In moments like these, art has the power to simultaneously crush and elevate the human spirit.

A little over a year ago, I was inside an unusual theater space in Singapore, watching a production that explored the contemporary issues surrounding the plight of refugees around the world. One of the songs in Tamil, my mother tongue, recalled another day in another year when the same moon hung above the heads of two lovers who hailed from rivaling communities. One day, the lovers were separated by the politics of their nation. Soon, they were each in a new place. The same moon that once cast its luminous glow on them both felt different then. Each of them longed for another time, for something they knew they could never have again.

It reminded me of a poignant excerpt penned by poet Rajagopal Parthasarathy. In a work titled “Rough Passage,” he distills the pang of leaving one’s homeland.

There is something to be said for exile:

You learn roots are deep.

That language is a tree, loses color

under another sky.

I’m an immigrant to the United States, and I’m able to relate to how, with every passing year, I miss the country of my birth some more even though I’m fully aware that I belong elsewhere. Feelings about places run deep. For emigres, there’s a heavy and unspeakable sadness in the idea of exile.

As the world engages in greater conflict, the list of victims grows only longer. By May 2022, more than 100 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide by persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

For Rupy Tut, one line of their show continues to haunt her because, so often, history keeps repeating itself. “To have so much hate for someone. How can humanity forgive this?,” she asks during the show. She sees that no lessons are learned. “The questions remain the same, and they keep getting asked.”

Judging by the state of the world, “Broken Seeds Still Grow” may be topical for a long time, outliving even its creators. What comes to mind are the words of Urvashi Butalia, author of “The Other Side of Silence: Voices From the Partition of India.” As her research progressed on the subject, Butalia realized that “Partition was surely more than just a political divide, or a division of properties, of assets and liabilities. It was also, to use a phrase that survivors use repeatedly, a ‘division of hearts.’”

Sponsored by the nonprofit Society for Art and Cultural Heritage of India, “Broken Seeds Still Grow” will be staged 3 p.m. Saturday at Bankhead Theater, 2400 First St., Livermore. For tickets, $10-$60, and more information, visit https://livermorearts.org/events/broken-seeds-still-grow-2/.