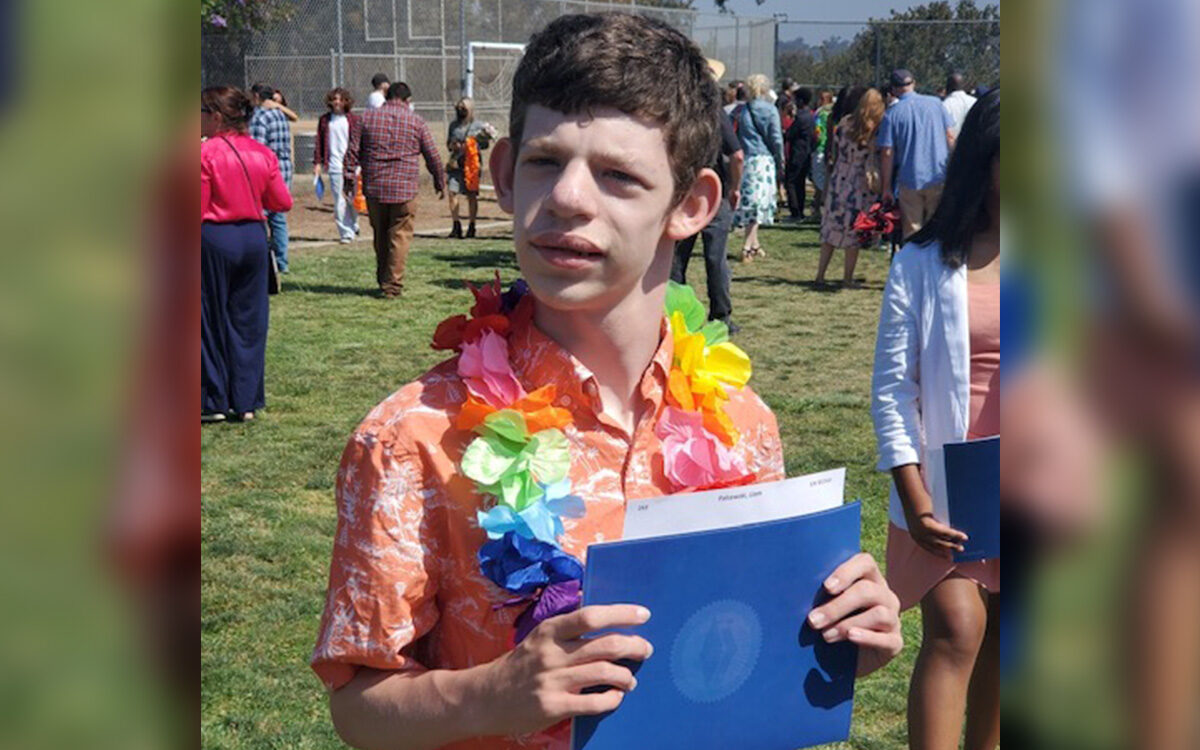

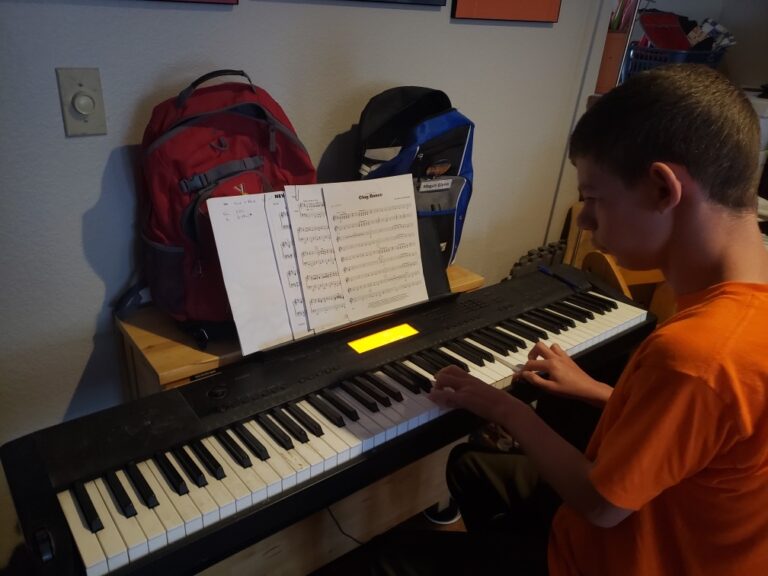

Megan Glynn’s son, Liam, started playing piano at age 4. With perfect pitch, he sails through Mozart and Vivaldi, can play anything he hears on the radio and shines when performing with the school orchestra.

But because he has a significant developmental disability, he cannot earn a high school diploma, and therefore his dream of becoming a classroom music aide is just that — a dream.

“He’s not being prepared for college and career, like other students are,” said Glynn, who lives in San Diego. “Just about every job is off limits to him, except maybe being a Walmart greeter. He doesn’t have the options that other students have, and that’s upsetting for all of us.”

But under a new program funded in the state budget, students like Liam, who have significant cognitive disabilities, would be able to earn high school diplomas based on the state’s alternative achievement standards and coursework tailored to their abilities. Potentially 80,000 students — 10% of the overall number of students enrolled in special education in California — would benefit from the new pathway.

Advocates for students with disabilities hailed the idea, saying it’s long overdue. A high school diploma for students who’ve worked hard and met their academic goals opens doors to further schooling, more meaningful careers and other options for a fulfilling life.

“Creating a path for every learner to earn a high school diploma helps eliminate unnecessary barriers to employment and community inclusion, which is what we want for every young person,” said Kristin Wright, executive director of equity, prevention and intervention for the Sacramento County Office of Education and former head of special education for California. “To me, it’s another important step in acknowledging and honoring neurodiversity and creating greater equity in our system.”

Currently, most students with significant cognitive disabilities earn a “certificate of completion” from high school, not a diploma, because they can’t meet the state graduation requirements.

Some of those requirements are attainable for students of all abilities, such as physical education and art, but few students with intellectual disabilities can overcome algebra and biology.

Compounding the challenges, some school districts have diploma requirements that surpass those of the state. They mandate that all students complete the A-G coursework required to attend a public university in California, which includes two years of a foreign language and three years of college-preparatory math — all but impossible for students with cognitive disabilities.

The new pathway would take advantage of a provision under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act that allows students with significant cognitive disabilities to earn a diploma if they meet California’s alternative achievement standards, with support through their individualized education program, the educational roadmap created by teachers, therapists, parents and others involved in a student’s schooling.

Advocates have been fighting for this for at least a decade. Several other states offer similar options for students with cognitive disabilities, and California already offers alternative diploma pathways for certain groups of students, such as those whose education is disrupted due to being homeless, in foster care or migrant.

In 2020, the state budget set aside money for a workgroup to study the issue and come up with recommendations. The workgroup’s report, published last fall, addresses the details, including transcripts and whether students continue working toward their diploma after they turn 18 (they can).

The 2022 budget, passed in June, included $1 million in federal funds from the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act to bring the workgroup’s recommendations to reality. The new pathway could be implemented as soon as next year. Although it’s not required, the state is encouraging all districts to adopt it.

Sue Sawyer, president of the California Transition Alliance, a nonprofit that helps people with disabilities after they finish school, has been working on the issue since 2013. The primary reason for the new pathway, she said, is new research and understanding of what people with cognitive disabilities are capable of.

“Our expectations have changed. We now expect people to go to work,” Sawyer said. “It’s real simple. If you leave school without a diploma, it shuts doors. If you have a diploma, you have options. I’m excited about the future because even though we still have work to do, I think we’re on the right path.”

Joyce Clark, co-director of the Exceptional Family Resource Center in San Diego, said a pathway to a diploma won’t solve everything for students with disabilities, but it’s a crucial step toward further education, rewarding careers and higher incomes, which could lead to greater independence.

Her son Luke, who’s 33, would have benefited from a diploma, she said. Luke was exuberant when he graduated from high school with his class, but all he could bring home was a certificate of completion. He now works part-time at a grocery store, but she believes he’s capable of much more.

“Is a diploma just a piece of paper? Yes. But it’s also connected to achievement,” Clark said. “It’s connected to access, to equity, to opportunity, to quality of life.”

For Glynn’s son, Liam, who’s starting high school this fall, the diploma pathway could help him take more meaningful classes, such as music, and fewer special ed classes focused on “life skills,” such as cooking and cleaning. She’d like to see him eventually enroll in a community college and continue to study music, his passion, while preparing for a career that builds on his talents.

Glynn is hopeful, even if her son’s district adopts the new pathway too late for Liam to benefit.

“Right now, he’s being set up to be dependent for life. Instead of learning academics, he’s learning to fold pillowcases,” Glynn said. “But even if it’s too late for him, I care what happens to the next students. They all deserve options and opportunities.”