The plight of undocumented students often gets told through the pursuits and failings of policy that can feel like alphabet soup – DACA, Prop 187, AB 540.

Putting a face to those stories is important for us to be able to understand, in human terms, why California and the nation must chart a path forward for thousands of students who face uncertain futures.

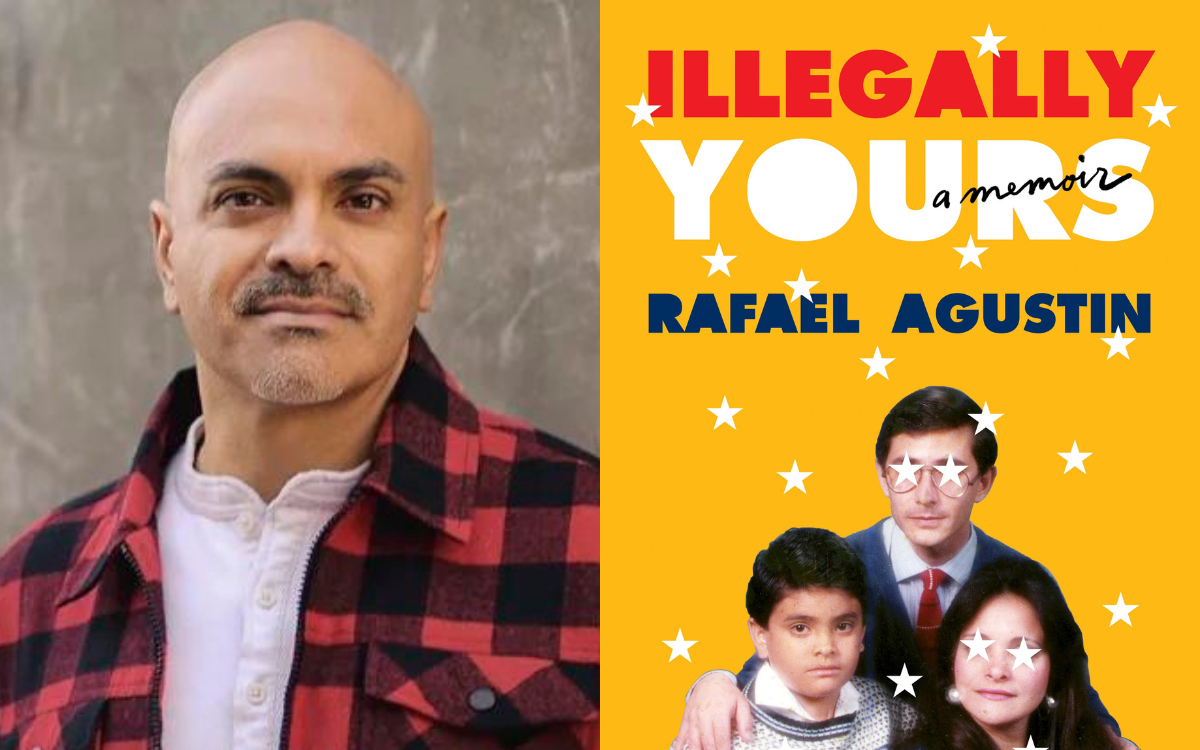

Meet Rafael Agustin.

Having arrived in California at age 7 from Guayaquil, Ecuador, Agustin offers a rare glimpse into the world of an undocumented student in his new memoir, “Illegally Yours,” published by Grand Central Publishing and available at Barnes & Noble, Amazon and other retailers.

Known for his work as a writer on the TV show “Jane the Virgin,” Agustin, 41, now serves as the CEO of the Latino Film Institute, which hosts the annual Los Angeles Latino International Film Festival, as well as a statewide arts program called Youth Cinema Project that aims to close opportunity and achievement gaps by training future filmmakers.

A graduate of UCLA’s prestigious theater program, his path to higher education was fraught with obstacles that remain for many students who have since walked in similar shoes. He credits his legal troubles and California’s community colleges for helping him find his way forward.

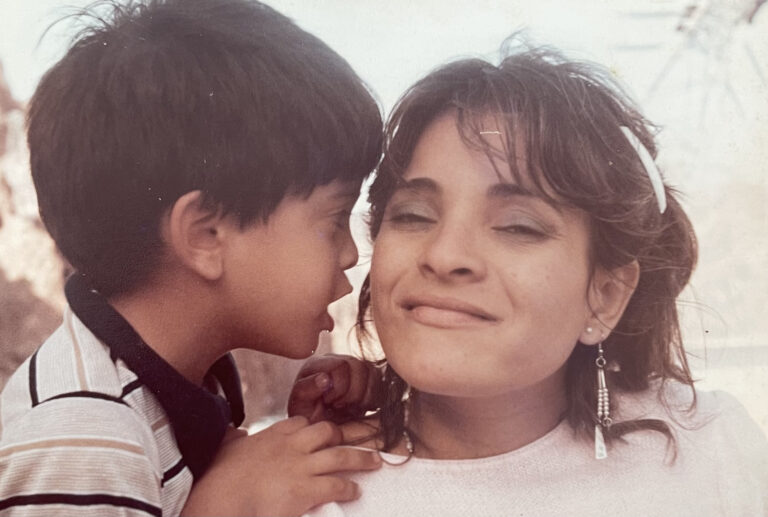

Agustin spent his early years in California on the move as his parents — both college educated and practicing doctors in Ecuador — struggled to find opportunities.

(His father went from pediatric surgeon to car wash attendant. His mother, an anesthesiologist in Ecuador, found work at a local Kmart.) As Agustin frames it: “…the greatest lesson my parents ever learned in this country was that the American Dream is not for you, but for your children.”

Agustin and his parents first came from Ecuador to Walnut, Calif., to be near relatives, but quickly moved on to other Southern California cities, including San Clemente, Thousand Oaks, Panorama City, Monrovia, Duarte and West Covina.

Along the way, he witnessed the haves and have-nots of public schools.

“I saw the very best and the very worst schools our state had to offer,” Agustin told me last week, as we swapped stories of growing up living between two cultures. “The difference was always funding, and how Black and brown schools got the least of it.”

Spending time in Thousand Oaks is where Agustin said he hit his stride: “I was noticed. I made friends, and my teachers were attentive. Well-funded schools just hit different.”

Getting grounded in school up until that point had been difficult, and he felt as though he was “slipping between the cracks” in his previous schools. “First it was my lack of English, then it was my lack of friends, but ultimately, it was my lack of stability,” he writes. “We moved so much that I couldn’t catch up in most learning environments.”

Agustin’s time in Thousand Oaks, however, was fleeting. The family moved several more times, and Agustin would ultimately go on to graduate from West Covina High School in 1998, the same year that Proposition 227 was passed by voters, essentially requiring English-only instruction for English learners. Even in the years prior to the English-only movement, Agustin described his experience learning the language as “sink or swim.”

Like many English learners, at a young age he became very involved in adult matters inside his home: “I became the official translator of our household. Any phone calls, teacher conferences or conversations with the landlord included me as my parents’ official English language representative.”

One conversation he was not privy to?

The fact that they had overstayed their tourist visas and were undocumented while their petition via the family reunification program slowly worked its way through the system.

His parents had hoped the paperwork would be resolved by the time Agustin graduated from high school and began applying for college. Instead, he inadvertently learned of his predicament when he went to the DMV to apply for his driver’s license and asked his parents for his social security number. He didn’t have one.

California schools don’t track the immigration status of students, but the Migration Policy Institute recently estimated that 145,000 students ages 3-17 are undocumented. At California’s public higher education institutions, there are an estimated 4,000 undocumented students enrolled in the 10-campus UC system, about 9,500 at California State University’s 23 campuses and up to 70,000 in the state’s 115 community colleges.

While Agustin was far from alone in his circumstances, navigating immigration matters in the climate of the 1990s in California was downright scary. In 1994, Republican Gov. Pete Wilson championed the ballot initiative Proposition 187, which was passed by voters and looked to cut public services to undocumented immigrants, including denying them schooling and healthcare. It also would have required teachers to report to authorities students that they suspected of being in the country illegally.

Agustin tried his best to take control of his precarious situation by channeling his energy into being an involved and popular student: He was elected senior class president. He made the prom court. And he joined his friends in applying for college.

“My parents didn’t understand any of the American college application process or — quite frankly — if I could even attend college,” Agustin recalls in his memoir. “I applied anyway. I tried not to think of the consequences.”

Like so many before him and many others who have followed, Agustin found his future at California’s community colleges. Three, to be exact. He enrolled at multiple campuses in order to exceed the number of credits students were able to take in one semester: “This immigration purgatory, the idea that I might spend another five years or fifteen years waiting for our petition to be approved, caused me to take every class in the course catalog, simply to take advantage of it in case I got deported.”

He went in alphabetical order: anthropology, biology, chemistry, economics and so on. By the time he got to “S”, Agustin had been told about Mt. San Antonio College’s award-winning speech and debate team. He joined and found his passion in giving speeches to entertain.

As his path came into focus, Agustin applied to transfer to the theater program at UCLA. His lack of a social security number continued to be a stumbling block but, as he had done before, he threw caution to the wind and applied anyway.

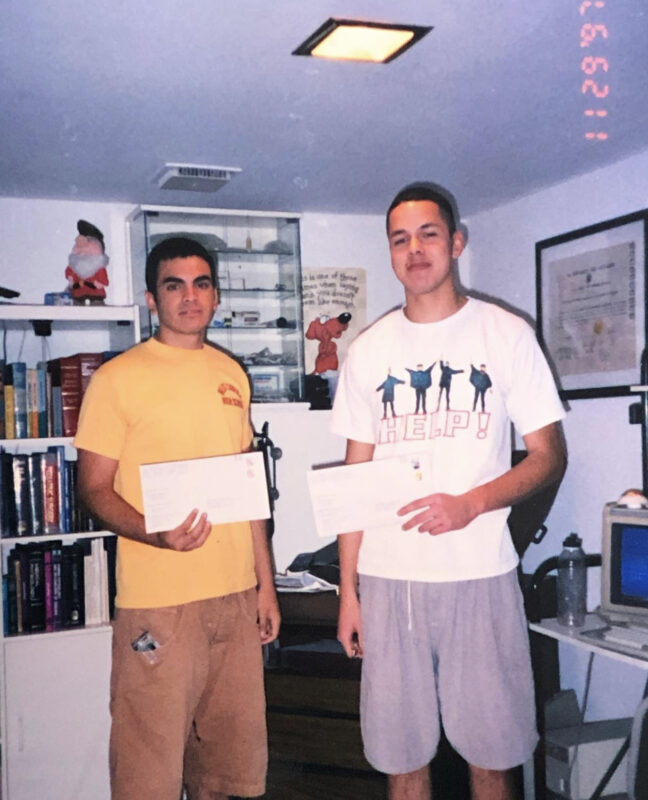

When he returned from a national forensics competition in Washington, D.C., Agustin found two envelopes waiting at home in the mail: One was a letter of acceptance from UCLA. The other was the family’s acceptance letter for permanent residency.

He’d spend the next three years earning a bachelor’s degree, followed by a master’s, in theater, all the time commuting from West Covina to Westwood. He’d take the Metrolink to the subway and then take a bus to campus each day, often beating the janitorial staff to school.

“People always see our shine, they rarely see our grind,” Agustin posted on his Instagram account, following a story about his work championing diversity in Hollywood.

To the hundreds of young students served by the Latino Film Institute’s Youth Cinema Project, Agustin had this parting message in his memoir: “If I could go from being an English learner to writing for English-language television, then you can accomplish anything.”

———–

Illegally Yours: A Memoir

By Rafael Agustin

Grand Central: 304 pages, $29