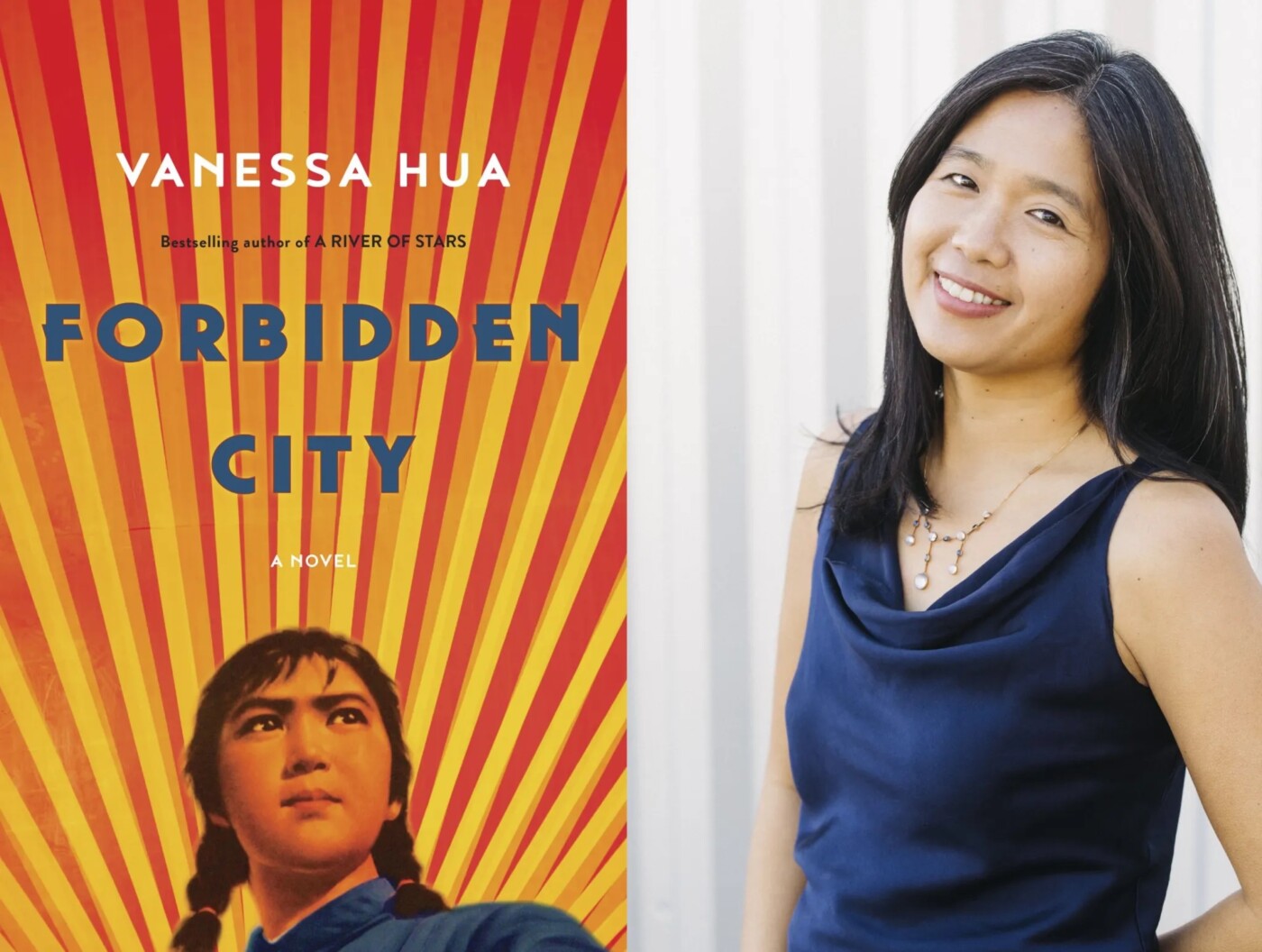

Something true: San Francisco is a place of reinvention. Breaching the peninsula comes with the ability to abandon who you were across the bay, across the ocean, across the world. For Mei Xiang, the protagonist of Bay Area author and journalist Vanessa Hua’s second novel, “Forbidden City,” a waitressing job in San Francisco’s Chinatown provides her the physical and emotional distance to recount her adolescent life in China amidst the Cultural Revolution in the final years of Chairman Mao Zedong’s life. Here, in Hua’s alternative universe, he’s called only “The Chairman,” and the close relationship Mei had not only to him, but also to his ideals for a modern China, molds her future.

But while San Francisco is Mei’s present, the book is almost entirely her past. She is the youngest of three daughters in a peasant family of starving farmers, and because of the timing of her birth in 1949 and Mao’s Great Leap Forward, she is the only one in her family who can read. She is also, at least initially, a believer in The Chairman and the progress he’s forced onto the country; while she knows many of the stories that trickle down to the villages are outdated and embellished, she nonetheless repeats the rumors that said “he no longer needed to s—, that he ate and drank nothing, that he was pure as jade and could grant our wishes.” On the cusp of 16, she is already poised to blackmail her neighbors for defying cultural norms.

Momentum begins when the Chinese government picks her for an opportunity to join a dance troupe in the “Forbidden City” aka Beijing’s Imperial Palace complex, now repurposed for the revolution. While the lure of proximity to The Chairman and veneration for her family sparkles, it also means she gets to eat.

But upon arriving at her new home at the repurposed Lake Palaces, she must learn the dynamics of this community of fellow poor girls plucked from obscurity to serve the whims of Party officials, including strategizing the best way to lose their virginities. Within this new ecosystem are Midnight Chang, Busy Shan and Dolly Yu, fellow teenagers grappling with defining their personhood in a time where women were “not even a footnote,” Hua says.

“From the beginning, I imagined there to be a retrospective narrator, 10 years after the events of the Cultural Revolution; she’s in San Francisco Chinatown by then,” she continues. “I felt that was really important, because I wanted to have a novel that, on one hand, took us into her youthful idealism, but also to be able to show her dawning disillusionment, and … you can only really get that with a retrospective narrator.”

Mei and her story have lived with Hua for more than a decade; it was the first novel she wrote — she began writing and researching it in 2007 — but she would not be able to bring it to print until after her publishing debut, the 2016 short story collection “Deceit and Other Possibilities,” begot a two-book deal. Her bestselling debut novel, “A River of Stars,” set in a relatively modern San Francisco Chinatown, was published in 2018. Life inevitably bleeds onto the page.

“Fourteen years is almost a third of my life. In that time, I went through huge transformations, personally,” Hua says. “But we also saw the rise of demagoguery, the #MeToo movement, the effects of isolation from the pandemic, the breakdown of social connections. What I came to realize about historical fiction is, not only does it give us a window into another time and place, but it helps us understand our own present in a new way, and that the past is never as distant as it seems.”

It all started with a photograph, which Hua saw back in 2007, of an aging Mao surrounded by girls at the height of their beauty and ingenuity. These girls were his concubines, his cheerleaders and clerks: But who were they, really? How had they served Mao and his cause in invisible ways? Hua interviewed women in China who were migrating to big cities from obscure villages, as well as older women who might have witnessed tribulations like Mei’s at the time. She was struck by how the most innocuous characters living under the radar in Chinatown had entire worlds buried inside them.

What Mei uses to demarcate herself from the pack quickly is not her dancing, but a shrewd eye for behavior and opportunities for ascension. Holding The Chairman’s attention is not enough; she must keep him endeared to her, if not by her beauty and intellectual prowess, then her strategy and affinity for deception. As she weathers what readers in 2022 call rape and a slanted political education from The Chairman, a new role emerges for her: as an instrument to humiliate “The President,” Chiang Kai-shek.

Soon Mei becomes, as Hua says another journalist pointed out, an Eliza Doolittle for The Chairman and one of his proteges, the young and opaque Secretary Sun. But she learns far more under their tutelage than refining her handwriting and rural accent. What she comes to realize, among the hours of drinking and studying and plotting with a man succumbing to the yet unnamed Parkinson’s disease, is that The Chairman is still just a man, and she will never be more than her usefulness to him.

Hua’s choice to refer to The Chairman by title only, and to depict his aging body sweating and trembling while he has sex with Mei, was a form of mortalization, of the vulnerability of the body.

“For Mei, and for me, it’s the fact of his body,” Hua says. “The visceral is how you raise that 2D character into 3D; to go beyond the replicable, recognizable image is to really consider him as a body moving through space, whether that’s swimming at the pool or out on the dance floor. It was really through writing that his character came about, through the same way that Mei understands him, through the five senses.”

Mei is also hyperaware of her own body: how it feels to be touched by the most important man in China, the strain of learning dances for the entertainment of others, the pangs of childhood malnutrition, the threat of pregnancy as an unwed teenager. She has learned how her body may be used, by her parents as a worker, by the government as a dancer and concubine, and as a mother. But it isn’t until she decides to escape that her body gets to be hers, though that will come with its own grief.

Like hundreds of millions across China, Hua’s protagonist deferred to the man whose portrait looked down on them as they ate as the embodiment of goodness and progress. But even though she was born into propaganda, it can be hard at times to root for Mei. She becomes excellent at lying, succumbs to groupthink and maneuvers among her peers motivated by jealousy and a desire to prove her superiority. While she’s not without instincts, her naivety is the point: It can be shaped, by the “Little Red Book,” by speeches, by subterfuge. She is technically the same age as the People’s Republic, and Hua hopes that readers see that they’re “both going through their adolescence in a way.”

The most compelling dynamic throughout Mei’s brief but roiling time at The Chairman’s side is with Secretary Sun. Through him, both the Party’s darkest methods and highest aspirations wash over Mei, and in return, he listens to her. What occurs between them, in a rare moment of vulnerability, effectively seals Mei’s yearslong journey to the Bay Area. What happens to Secretary Sun, as what became of Mei’s family, is lost to the consequences of history.

Teenagers are so sure of their realities, of their abilities to see what the older generations won’t or simply can’t. After a couple hundred pages and two charged scenes with both The Chairman and Secretary Sun, Mei finally makes a choice, a dangerous one, but one with which she finally gets to embrace her own opinions and follow her own ethics. In San Francisco, she is not yet 30, yet her narration bears the resignation of someone uninterested in further reinvention. It’s this looming span of life left to her that begs the question: What now?

“To her, I don’t think any happy ending is guaranteed,” Hua says. “She is a survivor; survival comes at a cost. What does it mean for someone to have survived this as a teenager, but still only be in her 20s? And how will that shape the rest of her life? I want the best for her, but I also know that nothing is going to get wrapped up neatly for her.”