“Let me tell you a story, about a movement that almost was …”

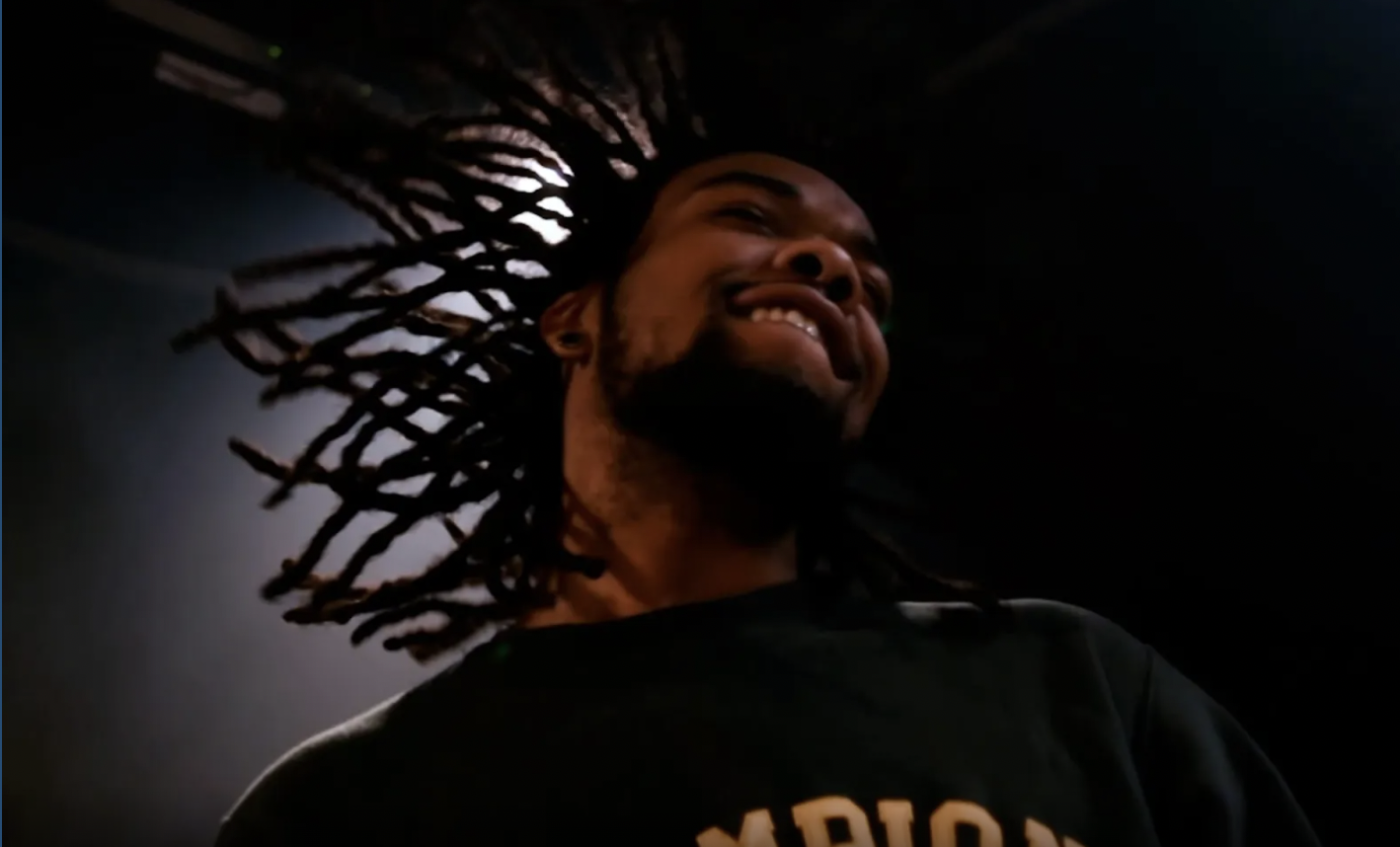

It only takes a few seconds. The first throb of bass, the palpitations of the 808s, the bars spoken through gold teeth. From the ears, it unfurls through the body: Your shoulders twitch, your head is buzzing, your knees want to dip. You are, for a few minutes, for a few verses, hooks and bridges, redolent with joy, with ecstasy, with the ability to do anything. And even when the song ends, your body remembers.

This is hyphy, and yet it is not — at least not entirely. For a generation of Baydestrians, to come of age was to gather at your block, trick out your scraper, keep your jeans and white T’s crisp, dance as if to dislocate your shoulders (aka “going dumb”), do doughnuts in the street.

The hyphy movement was a regional social, cultural and even political phenomenon with permeable timelines, but most agree it spanned the late ’90s to the mid-late 2000s, the peak coming in the summer of 2006 with national hits like “Tell Me When to Go,” “Super Hyphy” and “Blow the Whistle.”

It was the era of Mac Dre, of E-40, Too $hort, The Jacka, Turf Talk, San Quinn and many more artists you’ll hear bumping around the neighborhood even today. But it was also a period of distress, of fractured communities, gentrification, activism and cultural development in fashion, dance and language — yadadamean?

This amalgamation of community innovation (and I would argue, genius) that Bay Area native and filmmaker Laurence Madrigal attempts to document in his first feature length documentary, “We Were Hyphy.” In 84 minutes guided by the timber of “Blindspotting” star Benjamin Earl Turner, viewers are slid along the annals of hyphy’s emergence, climax and influence that cover the movement’s cultural tentacles in music, dance, fashion, slang and a 21st century cure for the ennui of the times.

There are the familiar, even reductive, visual symbols like shiny cars spiraling amidst the smoke of burnt tires, the mural homages to the late pioneering rapper Mac Dre and his thizz face, the aerial drone shots of Oakland. But within these is the affirming narrative that, no matter what happens to the Bay amidst deepening stratification, tech culture glut and unruly passages of time, the fact remains that, in the words of featured scholar Dr. Andrea L. Moore of CSU Sacramento, “the countercultures that come out of the Bay Area alway speak to this rebellion of dominant society.”

“I really wanted to capture that kind of coming-of-age moment in the movie from the perspective of the Bay Area in 2006,” says Madrigal, who grew up as a third-generation Bay native in Antioch and had already steeped in hip-hop culture for years by the time hyphy was gaining traction. “The Bay Area is all I’ve ever known. I was exposed to a lot of not just diversity and culture, but Bay diversity, culture, people.

I don’t think they realize [outside the Bay] the kind of grandiosity of the culture beyond just the music, and that is all connected. It’s not just a silly kind of fun act, saying-funny-words kind of thing.

It’s a rooted, powerful movement that, I would say, is as powerful as the ’60s hippie and counterculture movements.”

The peak he argues in the film, summer 2006, was the summer before his senior year of high school. He is a first-person account, a self-described “encyclopedia” imbued with the Bay’s do-it-yourself attitude. It was after he attended San Francisco State University’s film program that he realized the true scope of what filmmaking could be and that the idea to straddle these worlds crystallized. With producer Jason O’Mahony and homespun executive producers including photographer and Thizz Nation record label president D-Ray, rapper and producer Nump and “Blindspotting” actor, writer and showrunner Rafael Casal, Madrigal began working on the film four years ago and continued through the pandemic. It was hyphy itself that helped him take the plunge.

“My perception of what hyphy was four years ago, when I started, to where it is now is massively different,” he says. “I always say the hyphy movement and the culture really does instill our confidence and individuality. It gave me the freedom to be like, ‘I can be creative and be whatever I want and not really give a f— about what other people think.’ I wanted to make a movie for something I care about and was so thankful for. The last 5-10 years, there’s been a lot of attention on the Bay Area, especially the stuff that’s more digestible to the mainstream, like tech. But there’s just so much more to the Bay Area than that.”

The film walks the line between bird’s-eye anthropological study and neighborhood intimacy as nearly two dozen interviewees, from journalists to producers to the hyphy tastemakers themselves and their disciples, braid their lived experiences into the story of an era they keep close to their hearts. While big-name hip-hop stars like Keak da Sneak, G-Eazy and Kamaiyah weigh in, the mention of the majority of sources might draw blank stares from outsiders.

Music producers Nump, Rick Rock, and Trackademicks, local conduits of hyphy history like Thizz Nation CEO Kilo Curt, hyphy photojournalist and historian D-Ray, and car connoisseur Sideshow Tone provide nuance you can only cultivate by being in it, day after day, even as the hype dies down.

For Bay natives, this is a stroll through the neighborhood, but for outsiders, or even Bay transplants, it is finally answering the questions that come up as they venture deeper into this world: Why do they talk like that? Why are they dressed like that? How do they get their bodies to move in that way?

This Greek chorus of historians and creatives is one of the film’s greatest strengths. The influential producer Rick Rock can take credit for inventing a new musical vocabulary by lending his Southern roots with the preceding era of mobb music. Rapper, producer and E-40’s son Droop-E attests to hyphy production and the music’s content, the darker, more violent aspects of which are framed as a reflection of how life in the Bay Area was. Dancers like IceCold 3000 of the turf-dancing group the Turf Feinz (did you know “turf” stands for “taking up room on the floor”?) speak to how bodies translated the bass lines and frenetic drums into a new East Oakland dance form. But there are also young millennials like rapper and producer P-Lo, who embody how the past influences their own contributions to Bay Area sonic culture, as well as how they may interpret the future. And, of course, everyone loves Mac Dre.

The final third of the film delves back into sociopolitical circumstance, and the grief that comes with losing these leaders. Influential hyphy producer Traxamillion died earlier this year from cancer. Both Mac Dre and The Jacka were murdered, and Keak is now wheelchair-bound after surviving multiple shootings. Moore’s and KQED’s Pendarvis Harshaw’s contributions make clear the connections among hyphy culture, the crack epidemic of the 1980s, corrupt policing, gentrification and the recession.

The film isn’t perfect, but how could it be? Madrigal emphasizes that this is a benevolent project meant to cast the era in amber rather than interrogate its dark underbellies. Many of these artists were, because of a mixture of socioeconomic factors, justice-involved. Mac Dre’s near-deification frames his ascent as “the story of a person re-entering society” by Harshaw, which is not untrue, but leaves much unsaid. Too $hort’s 30+ year hip-hop discography, which serves as a mini-chronicle of itself of the evolution of Bay Area sounds, is rife with proud declarations of pimping women that go unquestioned. The violence documented within the quips and lyrical innovations are “what they saw that day,” but the question of who gets to tell those stories remains.

Similarly, women are sparse as both subjects and experts, even with Oakland native Kamaiyah’s enthused endorsements of the culture. Moore and D-Ray provide the most acute commentary on hyphy community dynamics and influence, but it doesn’t extend to how female artists contributed to the culture or what this generation of women took from “going dumb,” and the unique challenges that would drive them to seek hyphy out. The film does address the intersection of drug culture and how dangerous it was, but not so deeply as to derail the tonal reverence.

When the epilogue arrives, the film’s title, “We Were Hyphy,” becomes a misnomer. Hyphy does not live in the past; no one in the Bay refers to it in the past tense. The film also feels over far too quickly.

“That was a little frustrating for me: It was too hard to fit everything in and make it a compact movie,” Madrigal says. “The No. 1 priority was to make it a fun, nostalgic experience for the people that lived it, but also open up and make it approachable for people that have never heard of it. There’s so much that’s left out. I have a hunch that … 20 years down the line, there’s gonna be more reflection and research on this topic.”

Some of Madrigal’s documentary outtakes have become short films in their own right; the director has begun working on a series of hyphy “Side Stories” that get into the weeds of a particular pillar. The first, available on the film’s website, focuses on the story of Falcon Dave, the current leader of what could very well be the first African American car club, established 1979, The Falcon Boys. He is dubbed “a Bay Area legend.”

“We Were Hyphy” made its world premiere as part of the San Jose-based Cinequest’s pandemic-friendly streaming film festival called Cinejoy that ran April 1-17. The film is available for streaming now through June 12, via the 21st San Francisco Documentary Film Festival, and will make its in-person debut with SF DocFest on Saturday at San Francisco’s Roxie Theater. It is also among the opening-screening films showing at the San Francisco Black Film Festival on June 16 at the SF Standard Salon in San Francisco, and it will be featured in Cinequest’s return to its in-person festival this August, though exact dates haven’t been announced.

If you miss those screenings, Madrigal recommends keeping an eye on the film’s Instagram for further updates. Meanwhile, why not start with Googling everyone in the trailer? It’s not films that transmute memories, but people. I think hyphy historian Gary Archer said it best against the film’s closing shots: “You ask any kid right now that grew up in the hyphy movement, they’re gonna say ‘I’m just as important as any rapper.’ And they were. The greatest songs mean nothing if no one heard them.”

“We Were Hyphy” made its in-person debut as part of the San Francisco Documentary Film Festival on Saturday. It is available to stream via the festival through June 12. For tickets, $10 for streaming, as well as information about SF DocFest, visit https://sfdocfest2022.eventive.org/welcome.

The documentary will also be shown in person as a part of the six-film opening night event for San Francisco Black Film Festival taking place from 4:30-9 p.m. June 16 at the SF Standard Salon, 2505 Mariposa St., San Francisco. For tickets, $30, and more information about the festival, visit https://www.sfbff.org/.

Learn more about “We Were Hyphy” on the film’s website, https://www.wewerehyphy.com/, and its Instagram page, @wewerhyphy.

Thank you for you amazing review!