If you need an example of just how befuddling California’s top-two primary system can be, consider the case of the $50,000 mailer sent to voters across 13 California counties in early June.

The mailer’s message: In the crowded race for a state Senate district that sprawls from Modesto to Truckee to the Owens Valley, the only “Democratic choice” — the one with a “progressive agenda” — was local labor leader Tim Robertson, not school administrator Marie Alvarado-Gil.

“We Trust Only Tim Robertson,” the mailer blared in large type.

There’s nothing unusual about campaign material touting one Democratic candidate over another. Except that this one was funded by a Republican. And not just any Republican, but GOP state Senate leader Sen. Scott Wilk.

There were six Republican candidates running in that central Sierra district, but none were the beneficiaries of Wilk’s outside political spending. Nor were any championed by another independent expenditure committee that poured $17,000 behind Democratic Party-endorsed Robertson after receiving nearly $50,000 from Wilk’s account.

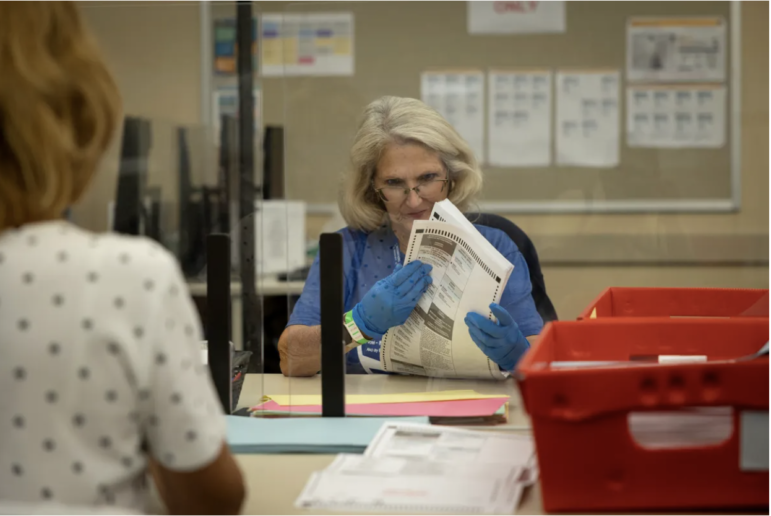

Though ballots are still being tallied at registrar’s offices across the district, now it’s clear what Wilk was trying to do.

In the Republican-leaning 4th state Senate district, 59% of voters in the most recent count checked their ballots for one of the half-dozen GOP candidates. But they diced up the vote into smaller slivers. The two Democrats, Robertson and Alvarado-Gil, only got 22% and 19% of the vote, respectively. But that was enough to put them in first and second place as of Monday.

The top Republican, former U.S. Rep. George Radanovich, is barely ahead of two others at 17% and insists the race is far from over. “We fully expect to be in the runoff,” said campaign manager Joe Yocca. “There are plenty of votes still left.” (In the nine counties completely in the district, about 163,000 ballots have been counted, with an estimated 62,000 to go.)

Under California’s unusual top-two primary system, all candidates are listed on the same ballot and only the first- and second-place winners move on to the November general election, regardless of party affiliation.

By backing Robertson and knocking Alvarado-Gil as insufficiently progressive, Wilk was trying to concentrate the district’s Democratic voters on one candidate, thus pushing the second Democrat’s support beneath that of at least one Republican.

If the current results hold, he failed.

Wilk said he decided to fund the mailer after seeing “scary” polling numbers a couple weeks before the June 7 primary suggesting that the Republican candidates were at risk of cannibalizing the GOP vote. Earlier in the year, he tried to persuade some of those Republicans to drop out to avert exactly this scenario, he said.

But by early June, it was too late. One strategy would be to pick a favorite Republican and spend money to persuade right-of-center voters to get behind them. But that went against a promise Wilk said he made not to put his “thumb on the scale” for any one of the Republicans.

So, as a last resort, he tried putting his thumb on the scale for a Democrat.

Comparing the results to those early polling numbers, Wilk said Robertson’s vote share ticked up slightly. “So it worked a little bit, but obviously it didn’t work enough,” he said.

Oddly enough, the California Democratic Party also landed on the same strategy in the final weeks of the campaign.

It spent roughly $50,000 boosting Robertson, believing that Alvarado-Gil was already safely in the top two. That Wilk seized on the same approach hoping to achieve the opposite outcome either speaks to a strategic miscalculation or terrifically bad luck.

“When you’re in the minority, you gotta think outside the box a little bit,” Wilk told CalMatters.

Wilk may have messed up, and too many Republicans may have entered the race. But in a broader sense, the upside-down results are the product of California’s decade-long experiment with a nonpartisan primary system — the top two.

Approved by voters in 2010 and rolled out for the first time statewide two years later, the system has changed state politics in many of the ways that its proponents promised at the time — and a few ways that they didn’t.

As supporters of the system claim, it’s offered an avenue for moderate members of both parties to amass more political power in the Legislature, while also giving “no party preference” voters — Californians who don’t belong to any party at all — a chance to participate in every major stage of the electoral process.

The ascendancy of the “Mod Caucus” — “a whole cohort of centrist Democrats” in the state Legislature — is thanks in part to the top two, said Dan Schnur, who worked as spokesperson for Republican Gov. Pete Wilson and the late Sen. John McCain of Arizona, before leaving the GOP and becoming an independent.

Political polarization remains, and sometimes the system produces odd results, but “I think it might be unfair to ask one political reform to solve all problems,” he said.

Supporters also assured voters that the top two would increase voter participation overall by engaging a broader range of voters, not just partisans. The truth is a bit of a mixed bag: Political independents can now freely participate in the primary, but many partisan voters are turned off if top-of-the-ticket races don’t include a member of their party. And there’s no evidence that non-voters are drawn to the polls by the state’s primary system, even while a series of other changes have made it much easier to register to vote. The percentage of eligible Californians who are registered to vote, at 85%, is the highest in 68 years. And since 2020, ballots have been mailed to every registered voter.

Still, like any electoral system, it’s not without its drawbacks. Critics say it too regularly produces head-scratching outcomes, like the apparent result in Senate District 4; limits voter choice; makes primary races more expensive and thus dependent on big spending by special interest groups; and is uniquely ripe for well-funded “shenanigans.”

Theory versus practice

In an old-fashioned partisan primary, Democrats and Republicans vote in separate elections, and the winners secure a spot on the general election ballot. The critique of that arrangement, made forcefully by supporters of top two, is that any candidate hoping to make it past the primary has to appeal to the party’s base. Those voters disproportionately occupy the ideological extremes, the argument goes, so partisan primaries lead to more extreme candidates and officeholders, which leads to gridlock.

“We have hyperpartisan on one side, hyperpartisan on the other, and we can never come together to do the people’s business in California,” then-Lt. Gov. Abel Maldonado, the man responsible for putting top two on the ballot, told voters in 2010.

By putting all candidates on the same ballot where they have to compete for votes across the ideological spectrum, top two encourages politicians to move toward the political center, the argument goes.

Since most legislative and congressional districts in California are overwhelmingly Democratic, the top two candidates in many districts are likely to be two Democrats — often a progressive and a moderate. And that gives voters in those districts a more meaningful choice that better reflects that district’s political preferences.

Or as FiveThirtyEight founder Nate Silver explained as California was considering the change, if every state helds its primaries this way, “we’d have a Senate full of Susan Collinses — and Joe Liebermans,” referring to two New England moderates.

That’s the theory. A decade into California’s electoral experiment, not everyone thinks it’s worked so well in practice.

In last week’s primary, the fantastically expensive five-way competition to be state controller resulted in a victory for Republican Lanhee Chen and, it appears, progressive Democrat Malia Cohen. Steve Glazer, among the most conservative Democrats in the state Senate who could serve as poster boy for the top two, didn’t make the cut. The polarized outcome more or less reflects what one might expect from a partisan primary.

Likewise, in the races for governor and attorney general, voters in November will not see the liberal Democratic incumbents square off against moderate Democrats or independents, but against long-shot Republicans.

After legislative primaries in Democratic strongholds in Sacramento, Hayward, Inglewood and San Diego, voters will see two Democrats square off in November. But from San Mateo to Milpitas to San Luis Opisbo; from Palmdale to Moreno Valley; from Norwalk to Anaheim, many of the state’s solidly blue legislative districts eschewed picking Democrats in the top two, instead opting for traditional partisan standoffs pitting a Democrat versus a sacrificial Republican.

“This system is not delivering on all the promises of providing opportunity for middle-ground candidates,” said Rob Stutzman, a GOP consultant who has run campaigns for moderate Republicans and political independents.

But Alvarado-Gil, one of the apparent top two Democratic finishers in the Senate District 4, considers herself a “middle-ground candidate.” A charter school administrator who described herself as a “proponent of less government,” she seems as surprised as anyone in the California political establishment at her success.

“I’m on quite the ride right now,” she said in a phone interview. “I don’t know if there’s a word to describe this other than, ‘Wow!’”

Alvarado-Gil said it wasn’t until two weeks before the primary that she heard from a politically-connected friend that she was polling surprisingly well for a candidate with less than $10,000 in her campaign account and no — literally zero — endorsements. When the Wilk-funded mailer attacking her landed in her mailbox, she knew her success in the polls was no mere rumor.

“I was just thrilled because they had a great picture of me,” she said.

Now that the results are in, she acknowledged the “paradox” of the apparent double-Democratic win in a district where Republicans outnumber Democratic voters by more than three percentage points and where Donald Trump narrowly defeated Joe Biden in 2020.

“I have many Republican friends, and I am willing to earn the vote of Republicans who believe that a moderate representing their district is a solid choice,” she said.

Robertson, the Democrat in first place so far, declined to comment in detail on the results or on Wilk’s involvement, saying that he is focused on his own campaign.

Shutout dread

The fate that apparently befell Republicans in Senate District 4 isn’t especially novel in California. Almost every year, the prospect of one party getting shut out from the November ballot, because an overabundance of candidates splits the primary vote, sends activists and political strategists into flights of panic.

In 2018, the terror was on the Democratic side. With hordes of fresh-faced candidates motivated to run in competitive congressional seats by a shared distaste for then-President Trump, party leaders warned of an “overpopulation problem.” In the end, the fear was overblown. Democratic candidates made it to the top two in all seven of the California congressional seats targeted that year — and went on to flip them all.

In fact, it was the GOP that suffered a surprise shutout that June when Democrats claimed first and second in a toss-up Assembly district in San Diego — thanks to an overly crowded Republican field and some last minute Dem-friendly misinformation about the top GOP candidate.

In 2020, it was Democrats’ turn to crowd themselves out of a possible legislative victory. Five little-known liberals entered the field against two Republicans in an Assembly district in Southern California. The two Republicans came first and second, despite securing less than half the total vote.

No wonder that back in 2010, both major political parties, preferring to have more influence over the candidates who run under their banners, found common ground in opposing the top-two measure. California’s smaller parties also opposed the idea, as did some political independents, who argued — correctly it turns out that — that in the vast majority of cases the top two slots will be monopolized by Democrats and Republicans.

With 10 years of California election data to work with — plus the experiences of Washington and Nebraska, also top-two states — the top-two system does seem to result in the election of more moderate candidates, but only by a bit.

“It’s not that it doesn’t have that effect, it’s just pretty small,” said Eric McGhee, a political scientist and researcher at the Public Policy Institute of California. “It’s not going to get us back to the 1970s or something,” an era with much more ideological overlap between Republican and Democratic lawmakers.

One complication that McGhee found is that voters often have a difficult time distinguishing between different ideological factions within the same party, so centrist candidates don’t always prevail even in districts where they would be expected to win.

“It’s asking a lot of the typical voter,” said McGhee.

Voters seem to like the system anyway. A statewide PPIC poll conducted in May found that 62% of likely voters say top two has been “mostly a good thing” for California.

The new lawn sign

But as voters have grown accustomed to the top-two primary, so have California’s political consultants and strategists, who have fine-tuned the art of gaming the system.

The consummate example might be in 2018, when Democrat Gavin Newsom’s gubernatorial campaign went out of its way to “attack” Republican John Cox, elevating his name recognition and conservative cred with GOP voters. That came at the expense of former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, a moderate Democrat who likely would have been a more formidable opponent to Newsom in a general election. Arguably, the two would have represented a more representative choice for California’s overwhelmingly Democratic electorate. But Newsom’s plan seemed to work, and he easily defeated Cox in November.

This year, a similar strategy played out when supporters of Democratic Attorney General Rob Bonta began touting the conservative bona fides of his Republican opponents, while doing their best not to mention the name of his no party preference opponent, Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert. As of Saturday, Republicans Nathan Hochman and Eric Early were battling for the second spot on the November ballot, both far ahead of Schubert.

In an Orange County congressional race, the Democratic campaign of Asif Mahmood name-checked a right-wing Republican, hoping to elevate him over incumbent Young Kim, though it doesn’t appear to have worked. And in a number of strongly Democratic legislative districts, candidates and special interests alike have toiled to prop up easier-to-beat Republican opponents — including, in one case, a QAnon conspiracy theorist who got some minor support from the California Chamber of Commerce.

In other cases — a Silicon Valley congressional race in 2014, a Stockton state Senate contest in 2020 — candidates have been accused of recruiting less-than-sincere challengers to flood the primary field and dilute the vote of the other party.

What was once a high-concept bit of electoral engineering has gone mainstream, said Paul Mitchell with Political Data Inc., a consulting and analysis firm that works with Democratic campaigns.

“Now you have someone in every little f—ing Assembly race trying to prop up the Republican,” he said. “It’s become a part of the process as much as lawn signs. It’s part of the California campaign war chest.”

Yet, while that tool may “look good on paper,” it’s not clear how often it actually works exactly as planned, said political consultant Andrew Acosta. For instance, Bonta appears likely face the more moderate Hochman rather than the arch-conservative Early targeted by Bonta’s ads.

And back in Senate District 4, Wilk’s effort to elevate one Democrat and pull down the other apparently didn’t work out, either.

Former state GOP Chairperson Ron Nehring blames the “idiotic” top-two system, but Wilk doesn’t. One of the Senate’s more moderate Republicans, Wilk represents a Southern California district that is more Democratic-leaning than any of his fellow GOP caucus members.

“I blame the Republicans candidates because none of them closed the deal,” he said. “I personally like the top two.”