Most California teachers have the appropriate credentials and training to teach the subjects and students in their classes, but many do not, according to new statewide data on teacher assignments released Thursday.

While 83% of K-12 classes in the 2020-21 school year were taught by teachers credentialed to teach that course, 17% were taught by teachers who were not.

Teachers are required to have either a multiple-subject, single-subject or special education credential to teach, depending on the grade level and coursework, but an ongoing statewide teacher shortage has meant that most school districts have had to rely on teachers who are not fully prepared to teach at least some classes on their schedule. Often that has meant teachers working with various emergency-style permits or waivers.

Map shows the percentage of classes taught by teachers with full credentials labeled by the state as clear.

“There is no question that well-qualified teachers are among the most important contributors to a student’s educational experience,” said State Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond. “California is committed to ensuring that every student has teachers who are well-prepared to teach challenging content to diverse learners in effective ways and are fully supported in their work. With this data, we can focus on measures to assist our educator workforce as they strive to provide high-quality teaching to all students, especially our most vulnerable students.”

The new Teacher Assignment Monitoring Outcome data is the state’s newest tool in its battle to end a long and enduring teacher shortage. It is expected to guide state and local leaders on how best to use resources to recruit and retain teachers and will inform California residents about teacher assignments in their local schools. It also allows California to finally meet federal Every Student Succeeds Act requirements.

“The release of the teacher data is a milestone achievement, years in the making,” said John Affeldt, managing attorney at Public Advocates, a public interest law firm. “We wish it had been here years ago but now the state will finally will have data capturing the quality of teaching force statewide down to the school level.”

The data will reveal disparities between low-income and wealthier schools in staffing fully prepared teachers, he said. Research by the Learning Policy Institute shows that the gaps have widened in California since the pandemic.

Students are more likely to have underprepared teachers in small rural districts where teachers are more difficult to recruit, according to the data. At Big Lagoon Union Elementary School in Humboldt County, 97% of the courses in 2020-21 were taught by interns, who generally have not completed the tests, coursework and student teaching required for a preliminary or clear credential. The school serves 24 students and has two teachers and a principal, according to state data.

Of the 10 school districts with the largest number of classes being taught by underprepared teachers, Oakland Unified has the largest enrollment — 35,352 students. Almost a third of the classes in the district that year were being taught by teachers working without the correct credential or training, according to an EdSource analysis of the state data that excluded charter schools.

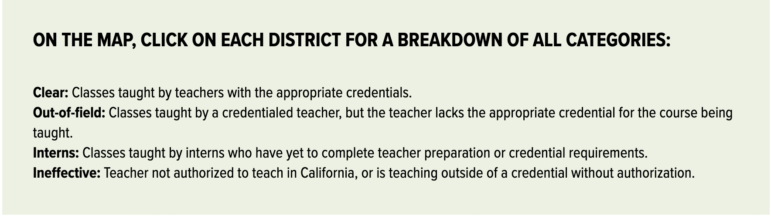

The new data categorizes teacher assignments as “clear,” “out-of-field,” “ineffective,” “interns,” “incomplete” or “unknown.”

It shows that 83.1% of the assignments that school year were clear because classes were taught by teachers with the appropriate credentials. Another 4.4% of the teaching assignments were deemed out-of-field because classes were taught by teachers who were credentialed but hadn’t passed required tests or coursework that demonstrate competence to teach the course or the student population in the class. Interns taught 1.5% of classes. Teaching assignments were labeled ineffective if they were taught by people without authorization to teach in California, or who were teaching outside their credential or permit without authorization from the state. Some 4.1% of courses had that designation.

Elementary schools had the highest percentage of clear teaching assignments — 90.6%, while media arts courses had the highest percentage of ineffective assignments at 34%.

Los Angeles Unified, the state’s largest district, was in line with the state average with 85% of its assignments clear, 3.3% out-of-field and 3.5% ineffective.

Other districts had a much higher number of teachers assigned to classes they weren’t fully prepared to teach. Maricopa Unified, Konocti Unified, Sierra-Plumas Joint Unified, Alpaugh Unified, Needles Unified, Oakland Unified, Chualar Union, Vineland Elementary, East Nicolaus Joint Union High and Borrego Springs Unified had 29% to 41% of their classes taught by an underprepared teacher in 2020-21 — the highest percentage among districts with more than 250 students.

There has long been concern about teacher assignments at schools in high-poverty communities. Oakland Unified, which has 72% of its students on free and reduced-priced lunches, was among the districts with the highest number of underprepared teachers.

Oakland Unified has had a teacher shortage for decades. It has been made worse by the pandemic. Over the past five years the district has averaged over 500 teacher vacancies each year. The complexity of the credentialing process, teacher diversity and the national teacher shortage have all played a part in the teacher shortages in Oakland, according to a press release from the district.

“I have the utmost respect for all of our teachers, whether they are currently credentialed, teaching outside of their subject area or in the process of getting their credential,” says Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammell, who noted she started her career with an emergency teaching credential.

In recent years district officials have increased beginning teacher salaries and increased recruitment and retention efforts.

School officials have numerous options that allow them to assign teachers to classes they aren’t credentialed to teach. Teachers who have not completed testing, coursework and student teaching can work with provisional intern permits and intern credentials. Credentialed teachers can teach classes outside their credential with limited assignment permits and waivers in order to meet staffing needs. School districts also can use the local assignment option to assign a teacher with a different teaching credential to a class when they can’t find an educator with the proper credential.

“Amidst a nationwide staffing shortage, school districts are struggling to find teachers for classes and sometimes must utilize the local assignment option to place high-quality teachers in assignments that they aren’t credentialed to teach, yet they are proving to be highly effective in,” said Kindra Britt, spokeswoman for California County Superintendents Educational Services Association.

Court and community schools run by county offices of education have a particularly difficult time filling positions, she said.

“We are putting the most qualified person in front of students,” she said. “The data doesn’t really support that.”

Darling-Hammond calls the shortage of appropriately credentialed teachers in some communities worrisome, but she is confident that recent state initiatives to recruit and retain teachers will increase the number of teachers in the state. The initiatives include $500 million for Golden State Teacher Grants, $350 million for teacher residency programs and $1.5 billion for the Educator Effectiveness Block Grant.

But there is still work to be done, Darling-Hammond said.

“A lot of people are beginning to recognize that retention is the name of the game,” she said. “It’s not about recruitment. Nine out of 10 positions are open because people left the year before.”

There won’t be any punitive action from the state if they have too many teachers without the correct credentials, although they may feel more public pressure now that the data is publicly available, Darling-Hammond said.

The data collection was mandated by Assembly Bill 1219, which passed in 2019. It also is the result of two years of collaboration between the Commission on Teacher Credentialing and the California Department of Education.

The information will be used to inform state and local education officials about where teaching shortages exist and how deep they are so that resources can be targeted to places with the most need, Darling-Hammond said. The data also can help the state improve programs by tracking the attrition rates of teachers who completed residency or other teacher preparation pathways, she said.

“As we begin to emerge from a global pandemic, this data is an important tool to drive conversations about how we can best serve students,” said Mary Nicely, chief deputy superintendent of public instruction at the California Department of Education. “By launching this annual report, we are providing a new level of transparency to support schools, students and families as we find ways to navigate today’s challenges to public education, including statewide education workforce shortages.”

The data is submitted to the state from school districts each fall, based on teaching assignments on the first Wednesday in October. The teaching assignments are then compared to teachers’ credentials by Commission on Teacher Credentialing staff. If a teacher’s assignment doesn’t match his or her credential, the school district and a state monitor will review the case, said Cindy Kazanis, division director at the California Department of Education.

More than 3,000 school employees were trained to use the new database at more than 30 in-person sessions and through several webinars, said state officials at a news conference on Wednesday.

But not all necessary employees had training or knew how to enter the codes correctly, resulting in many school or district entries being designated as incomplete, Britt said. The California Department of Education won’t correct the data, she said.

“Despite the confusing labels, our educators are effective; this issue is semantic, and we need steps to remediate the incorrect data,” Britt said. “I’m a little concerned about the damage that can be done to an already strained education workforce.”

Schools had time to review the data, including almost six months to submit, review, correct and certify their teacher assignment data, said Maria Clayton, director of communications for the California Department of Education. They then had four months in late 2021 to review the results after teacher credentials were compared to teaching assignments.

Britt said the California County Superintendents Educational Services Association is advocating for more training options for county offices.

The information on teacher assignments will be available to the public on the California Department of Education’s Dataquest website, and will be used in several other state and local reports including each School Accountability Report Card, the California School Dashboard, the Federal Teacher Equity Plan and the Williams Monitoring criteria.

Affeldt and other equity advocates are hoping the state board will include the information as a metric on the school dashboard to compel districts to address disparities among schools in teacher assignments. The board plans to examine the issue after the California Department of Information has released a second year of data.