As California races to prevent the irreversible effects of climate change, some experts are questioning key policies that the state is counting on to meet its ambitious goals and accusing state officials of failing to provide substantial details to back up its claims.

The California Air Resources Board’s proposal, called a scoping plan, outlines policies that would transition the economy away from fossil fuels. The purpose of the plan is to fulfill state mandates to reduce planet-warming emissions 40% below 1990 levels by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2045.

In this year’s highly-anticipated climate policy blueprint, some critics say the state agency has not been transparent on how it plans to achieve its goals. The process has left legislators and others at the forefront of the climate discussion confused over the air board staff’s projections.

“The draft scoping plan does California a disservice,” said Danny Cullenward, an economist and vice chair of the Independent Emissions Market Advisory Committee, a group of five experts appointed by the governor and top legislators to assess the effectiveness of the state’s landmark cap and trade program. “It focuses on long-term goals at the expense of near-term action.”

At two recent state committee meetings, environmentalists, academics and climate policy experts who serve on state advisory panels voiced concerns over California’s approach to tackling the climate crisis. They called the plan incomplete, ambiguous and confusing.

In addition, in a letter sent Thursday to the Air Resources Board and Gov. Gavin Newsom, 73 environmental justice groups called the proposed scoping plan “a setback for the state and the world.”

“It fails to accelerate our 2030 and 2045 climate targets, and it fails to increase the pace of California’s actions beyond existing commitments,” the letter says. “We need a plan that transitions us away from the extractive, fossil-fueled energy system at the pace and scale demanded by climate science and environmental justice.”

The Air Resources Board did not send representatives to speak at either of the two meetings — a joint Senate and Assembly committee hearing and the emissions trading advisory committee.

But in a response to questions from CalMatters, air quality officials said the plan is a “guidance document” and that specific emissions reductions would be detailed when individual regulations are drafted.

“It is not a final document, nor intended to be. It is also not a regulation. It is a guidance document and as such leaves room for new information that may become available later,” said air board spokesperson Dave Clegern.

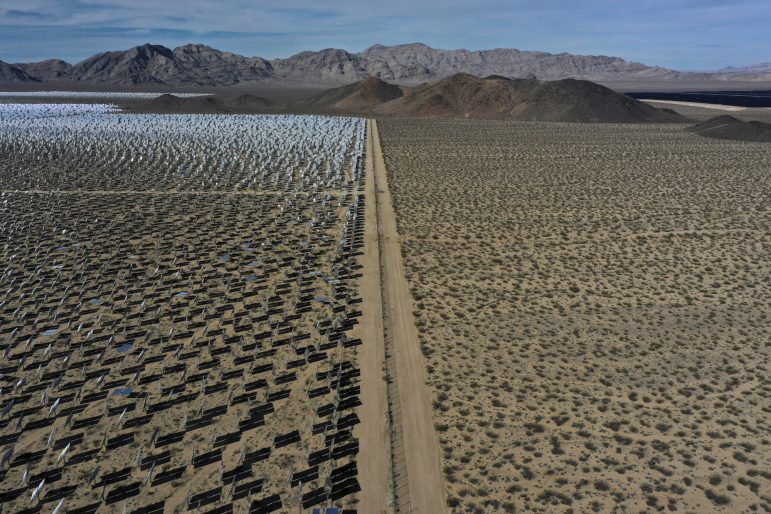

The plan focuses on increasing dependence on renewable energy, such as wind, solar and electric cars, and capturing carbon dioxide emitted by oil refineries and other industries.

The debate pits those who want to mandate an end to fossil fuels against those who want an approach that relies more on market incentives and technology.

Environmentalists have long viewed the use of carbon removal technology and cap and trade as continued investments in the fossil fuel industry. But others side with the oil industry, saying the state won’t be able to reduce carbon emissions fast enough without them. And across the political spectrum, many say the state’s approaches are too flawed to produce the results that the Air Resources Board says they will.

“In place of tangible strategies to reduce emissions, the draft plan aims to achieve far fewer emission reductions than other leading climate jurisdictions in the U.S. are already pursuing,” Cullenward said. “Nothing less than the future of California’s climate policy is at stake.”

The board plans to hold a public hearing on the plan on June 23 and vote in August.

Critics say staff haven’t provided much evidence of how some key components could work, including the state’s reliance on carbon removal and the role of its cap and trade program, which is a greenhouse gas market for industries that allows them to buy and sell credits.

Air board staff used modeling to predict how each sector of the economy will reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. In their draft plan, they say carbon removal technologies will help capture millions of tons of carbon dioxide at oil refineries and other industries that are difficult to decarbonize, such as cement.

The plan cites studies from Lawrence Livermore, MIT and other institutions about how the technology may work, but adds, “ultimately, the role for mechanical (carbon dioxide removal) will depend on the success of reducing emissions directly at the source.”

Air board officials included in their models that carbon capture technologies were deployed in 2021 and will ramp up quickly by 2030. The plan says about 2 million tons of carbon dioxide were captured in 2021 — even though no facilities exist in California.

But they acknowledged in the plan that this assumption was wrong: Use of the technology in California by 2025 is “unlikely, and those emissions will be emitted into the atmosphere.” They said they would revise their modeling in the final version.

Air board officials say reducing emissions alone won’t address the growing threat of climate change. The path to carbon neutrality cannot be achieved without extracting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, according to their analysis. In their plan, by 2035, 5% of total emissions would be eliminated through carbon removal technologies, and that drops to 3.5% by 2045.

Carbon capture is the practice of collecting carbon dioxide emitted by smokestacks, transporting it in pipelines and injecting it deep underground for long-term storage so it does not warm the planet. (The practice is different from biological sequestration, where carbon dioxide is stored in natural habitats, such as vegetation, forests, wetlands and soil.)

The Air Resources Board’s staff’s preferred option, known as Scenario 3, projects that carbon removal technologies will capture nearly 80 million tons of carbon dioxide from polluting facilities per year by 2045. The scenario predicts that carbon removal infrastructure will be installed on most oil refineries by 2030 and on all cement, clay, glass and stone facilities by 2045.

A panel of experts speaking at a meeting of the Joint Legislative Committee on Climate Change Policies on Tuesday discussed the pros and cons of carbon capture and storage and how it could inform the types of policies lawmakers push for. Much of the hearing centered on the controversy behind the practice and whether it did more harm than good.

The panelists provided vastly different accounts on its effectiveness, frustrating some lawmakers, who said the comments were inconsistent.

“The frustrating thing for me is that we have conflicts on what we’re hearing today, so how do I do the right thing for my constituents or the environment?” said state Sen. Brian Dahle, a Republican from Lassen County who is running for governor. “That’s very challenging for a legislator, sitting here with four panelists not all agreeing as we’re trying to move to the future.”

Some experts at the hearing said carbon removal plants could capture more than 90% of carbon dioxide emissions.

George Peridas is director of carbon management partnerships at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a federally-funded research facility. He said California is well-positioned to launch projects in parts of the state with deep sedimentary rock formations, including the Central Valley, which could serve as prime locations to store carbon dioxide.

“The Central Valley has a world class geology – that means just the right kinds of rocks for safe and permanent storage,” he said. “Carbon capture and storage is well-understood, heavily regulated, available for deployment today and has an overwhelmingly positive track record.”

Globally 27 carbon capture and storage projects are operating so far.

Mark Jacobson, a Stanford University professor of civil and environmental engineering, told the legislators that the state is overstating the impact of carbon capture and storage, citing the capture rate of existing facilities that have produced much lower results.

He said the net capture rate is much lower because the fuels that are used to operate the equipment offset the emissions it swallows.

For instance, the Petra Nova carbon capture and storage project in Texas, which operates on natural gas, was designed to capture 90% of carbon dioxide. But the emissions generated from powering the plant bring down the capture rate to about 33%, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The Shell Quest carbon capture and storage project in Canada has also been widely scrutinized. The plant captured 5 million tons of carbon dioxide since 2015, but it also emitted 7.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gases over the same period – the equivalent carbon footprint of about 1.2 million gas cars, according to a 2022 report from Global Witness, an international watchdog organization. That means just 48% of the plant’s carbon emissions were captured, according to the report.

“It’s nothing close to what we would need to solve a climate problem,” Jacobsen said. “Completely useless.”

Sarah Saltzer, managing director of the Stanford Center for Carbon Storage and the Stanford Carbon Initiative, said the technology will improve in the coming decades. She said the state should streamline carbon removal projects to advance its carbon-reduction goals.

“We cannot rely on renewables alone as we do not have the capacity,” she said. “We believe that including carbon capture and storage and a wide range of portfolio options for reducing emissions of carbon dioxide provide a way to deal with hard-to-decarbonize sectors.”

In its analysis, air board staff said the facilities could have more benefits as they increasingly become powered by renewables and more companies start to invest in them.

Carbon removal technology also has potential to produce hydrogen until the state can develop more hydrogen plants powered by renewables, according to the report. Most hydrogen today is produced by oil refining but officials expect the state will transition to “green hydrogen,”which is produced by splitting water atoms using renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

Environmental justice groups say carbon capture will prolong dependence on the fossil fuel industry. They also worry pipeline ruptures and leakages and the continued operation of polluting facilities would keep harming the environment and health of nearby communities.

In a plea to lawmakers, Steven Feit, an attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, said the state should not push for carbon capture projects if it truly seeks to phase out fossil fuels.

“Carbon capture and storage is pitched as one simple trick that can solve the genuine challenge of hard-to-abate emissions, but it may actually make the climate problem worse.” he said. “It will be a lifeline for emitting facilities and will lock in fossil fuels for decades to come.”

Jacobsen, of Stanford University, said the state should instead prioritize direct emissions reductions and renewables. “It can be done,” he said. “It’s far better to use renewable energy to replace fossil fuels.”

On the other hand, the oil industry is asking the air board to increase the plan’s reliance on carbon capture, saying it would ease the economic harm and job losses that would occur from phasing out fossil fuels.

“Our industry supports, invests in and is innovating towards more use of carbon capture technology,” said Kevin Slagle, a spokesperson for the Western States Petroleum Association, which represents oil and gas companies. “It’s simple, our state will not meet our climate goals without carbon capture and storage. This should be an area of agreement and opportunity rather than controversy.”

Implementing the scoping plan’s strategies would cost $18 billion in 2035, ramping up to $27 billion in 2045, the air board estimates.

The dispute over carbon removal mirrors a common refrain over the benefits of cap and trade.

In an earlier version of the scoping plan, air board officials in 2017 estimated about 38% of emissions reductions would come from cap and trade. But this year’s proposed plan leans more heavily on carbon removal technologies, a move that Cullenward said is “striking” considering the role the cap and trade program had in the past.

“The absence of an explanation is something that should be clarified,” he said at an Independent Emissions Market Advisory Committee meeting last week.

While the pace of emission reductions needs to more than triple to hit California’s 2030 target, just six pages of the 228-page scoping plan address how cap and trade is expected to contribute to that goal — with no detailed analysis of how significant that role will be.

Air board officials said they will evaluate the cap and trade program in 2023 and provide more details after the scoping plan is voted on by the board this summer.

The cap and trade program, which puts a price on pollution, has long been a key state policy to reduce pollutants emitted by companies that are subject to state emissions caps. But it also has been widely criticized by legislators, analysts and environmental justice groups. For years, companies have been banking the credits that allow them to pollute, creating an oversupply of allowances in the system that could deter them from meeting future emissions targets.

Catherine Garoupa White, a member of the state’s Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, said the plan should have included substantial reforms to the program, including a tighter emissions cap, reducing the number of allowances currently in circulation, establishing no-trading zones in disadvantaged communities and eliminating the use of offsets and distribution of free allowances.

“I continue to be frustrated by the lack of transparency and accountability from the Air Resources Board in this process overall,” she said.

“The explanation on cap and trade is very short and ambiguous in this giant document. The carbon market is unpredictable and there’s a lack of evidence that the program is going to provide the emission reductions that we need.”

Meredith Fowlie, a professor at University of California, Berkeley’s department of agricultural and resource economics who also serves on the state’s environmental justice committee, said it is critical to address concerns about the scoping plan and how cap and trade factors in sooner rather than later.

“The modeling is complicated…but given the high stakes, I think we’ve got to find a way to make it more transparent,” she said. “It’s essential that we tackle the issue right now.”