California schools with large numbers of high-needs students — low-income, English learners and foster youth — have always struggled to find substitute teachers, but this year’s COVID-19 omicron surge brought them to a breaking point.

The staffing crisis forced school administrators to find alternatives for full-day substitutes, such as math and reading coaches or a rotating cast of office staff, disrupting instruction for students who already may have been lagging academically. While school officials statewide worry about the possibility of another surge, they know teacher shortages are a constant reality, prompting one California legislator to propose funding to attract more substitutes.

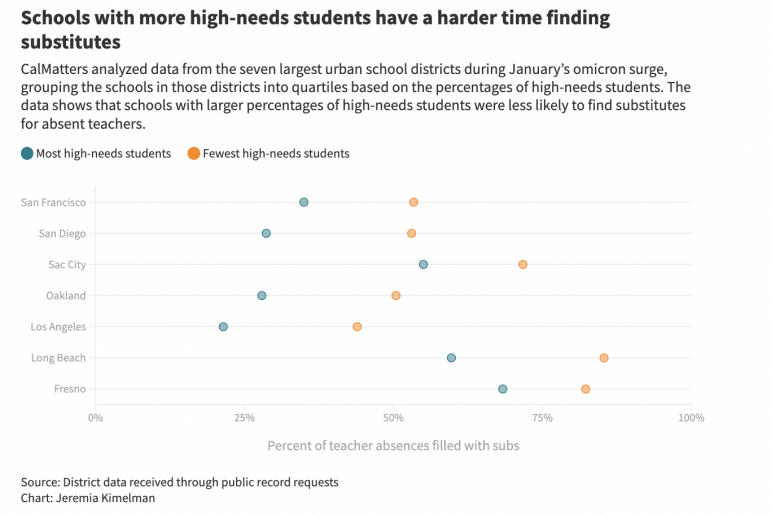

CalMatters analyzed data from the state’s seven largest urban school districts for January to determine where the substitute teacher shortage was most acute. The data shows that on average, the schools with the most high-needs students filled about 42% of their teacher absences with substitutes. The schools with the fewest high-needs students found subs for 63% of teacher absences.

But the disparities varied across the districts. For example, at Los Angeles Unified, schools with the most low-income students found substitutes for 23% of absent teachers. Those with the fewest low-income students found substitutes for 45%. At Fresno Unified, substitutes filled about 68% of absences at the schools with the most high-needs students, while they filled 85% at the schools with the fewest high-needs students.

“Unfortunately that doesn’t surprise me,” said Tara Kini, director of state policy at the Learning Policy Institute, a nonprofit education research organization. “It reflects long-standing patterns for both subs and permanent teachers.”

According to a 2021 study by the Learning Policy Institute, the substitute teacher shortage exposed and strained an underlying teacher shortage during the pandemic. Because some schools rely on short- and long-term substitutes to fill vacant teaching positions, a sub shortage means an even bigger disruption for schools that struggle to hire full-time teachers. And schools in low-income communities have always had a harder time hiring, a previous study found.

Officials at both Los Angeles and San Diego Unified, the state’s largest districts, said they had plenty of substitutes before the pandemic. Ileana Davalos, who oversees human resources at the Los Angeles district, said she “rarely had an unfilled absence.” Yet as California’s largest district, it faced the same crisis as others did during the omicron surge.

“When we hire you as a substitute, you pick the area that you want to work in,” Davalos said. “But during omicron we put out calls to everybody.”

Officials at many school districts said both substitute and full-time teacher shortages are not just a pandemic problem. Schools serving more low-income families have always been harder to staff, they say.

At Sacramento City Unified, teachers held an eight-day strike in late March to protest staffing shortages. While close to 70% of the district’s students qualify for free or reduced-price meals — the definition of low-income — the schools with fewer of those students had an easier time finding subs in January.

Ultimately, the teachers’ union — the Sacramento City Teachers Association — was able to get a 25% raise for subs, boosting their pay to about $280 a day. But in the event of another surge in COVID-19 cases, teachers union president David Fisher said the same schools will again be hit the hardest.

“It’s not that different from the teacher shortage,” Fisher said. “It affects the most vulnerable districts and the most vulnerable schools. These schools have the most turnover and the most difficulty attracting subs.”

When teachers are absent, schools post their openings and substitutes choose which ones they want to accept. Some substitute teachers say they have personal preferences for certain schools and sometimes avoid low-income communities.

District administrators say it’s not always a matter of choice. Those communities with large percentages of high-needs students had disproportionately higher case rates during the omicron surge, and substitutes who live in those neighborhoods might not have been able to work. Others say it really is harder for subs to work in low-income schools where more students are experiencing homelessness and food insecurity.

“There’s a lot going on in those classrooms,” said Nathalie Hrizi, the vice president of substitutes for the San Francisco Unified teachers union who is also running for California state insurance commissioner. “The substitutes are highly impacted by that because they don’t have the relationships that education is built around.”

San Francisco Unified tried to address these inequities with mixed results. A San Francisco ballot measure passed in 2008 levied a local parcel tax that helped fund benefits and higher pay for substitutes who work for certain high-needs schools.

Those subs make $241 a day compared to the standard rate of $225 a day for their first 10 days of work. Their pay is then bumped to $271 a day. But the 23 schools selected for the program on average filled less than 30% of their teacher absences with substitutes during the January surge. Districtwide, schools on average filled 45% of their teacher absences.

No San Francisco Unified officials would be interviewed, but district spokesperson Laura Dudnick said the district is actively recruiting subs and that many districts in the region are facing a “dire substitute shortage.”

Cindy Diaz, a substitute at Long Beach Unified, said subs worry about their personal safety working in neighborhoods that have reputations for violent crime. She said some subs who don’t speak Spanish will avoid schools with high numbers of English learners.

“It’s about the unknown,” she said. “Is it a safe area for me to park? Am I going to need to worry about my personal safety? Am I going to have a problem with discipline?”

The challenge of being a sub

While some schools are overlooked by subs, subs themselves often feel underappreciated.

“Office staff sometimes try to bully you into giving up your free period and take extra classes,” said Patricia Wallinga, an aspiring music composer who relies on substitute teaching at San Francisco Unified as her main source of income.

She caught COVID-19 in January. At the time, she was working as a long-term substitute for an advanced English class.

Wallinga started working as a substitute in late 2019, just before the pandemic. She stopped in March 2020 when schools statewide went virtual, and there was less demand for subs as teachers worked from home. The number of new substitutes statewide that year plummeted.

Data from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing shows that the state issued 15,251 substitute teaching permits in the 2019-20 school year. The following year, it issued 9,265, the largest drop in five years.

But when schools reopened in the fall of 2021 and substitutes like Wallinga returned to working in-person, the state’s supply of new substitutes swelled. According to David DeGuire, a spokesman for the commission, as of last month 22,759 new substitutes received permits this school year.

Diaz, the sub at Long Beach Unified, said she felt more appreciated this year by office staff, especially during the omicron surge.

“They take the time to say, ‘Thank you for coming in,’” she said. “They used to act like they’re doing me a favor.”

While some subs avoid schools with more high-needs students, Wallinga said the main factor for her is location. She only works at schools that are close to her home and reachable by public transportation, and chooses jobs based on the quality of the lesson plan the teacher leaves her.

“It’s night and day,” she said. “These kids know when they’re cared for and when they’re not.”

She has worked at both low-income and higher-income schools and said the disparities are obvious.

“I think, gee, this school has a 60-piece orchestra, and this school doesn’t have pens,” she said.

In California students from low-income households score lower on standardized tests and are less likely to graduate high school. Substitutes and teachers say instability in students’ home lives can lead them to be disruptive in class. While teachers can develop trusting relationships with these students, substitutes say they have a harder time forming that bond during their short stints in the classroom.

David Zaid, who oversees human resources for Long Beach Unified, said the district tried to address this issue by placing one or two permanent subs at certain high-needs schools.

But those measures weren’t enough when the substitute teacher shortage devolved into a crisis. Zaid said reading coaches and office staff filled in for teachers when schools couldn’t find enough substitutes.

Debbie Miller, a teacher at Hamilton Elementary in San Diego, said reassigning literacy or math coaches can take away essential resources from students who need them most. Her school, where nearly all students come from low-income families, filled just 20% of teacher absences with substitutes in January.

“These teachers might be working with reading groups with kids who are two years behind in reading,” Miller said. “When they’re called in to cover classes, those kids don’t get the extra support for two days, three days or even weeks.”

Diaz said most teachers have a roster of go-to substitutes. “Some teachers really like their subs,” she said. “They’ll rearrange their plans to get the substitutes that they want.”

Fisher, the union president at Sacramento City Unified, said substitutes are likely to avoid schools that have a reputation for high turnover and for having a shortage of experienced or permanent teachers.

“It’s a much more challenging environment going to a school that has multiple subs and multiple vacancies,” he said. “More stable permanent staff means more aide support and more parent support.”

Looking ahead

Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia, a Democrat from Coachella, authored legislation in February to help districts hire and train substitutes and increase their pay.

“One of the things we’ve discussed with the committee team is how we elevate the districts that need the most support,” Garcia said. “We’re hoping to ensure that those things are taken into account.”

The bill, which is currently in the Assembly’s Appropriations Committee, would provide $100 million in state funding to local districts. But it currently doesn’t contain any incentives for focusing on schools with more high-needs students.

Garcia said he’ll consider amending the bill to provide more support for the schools that have the hardest time finding substitutes.

Substitutes do say they need more training on managing student behaviors. And while some substitutes enjoy the freedom of choosing where they work on any given day, others say they should be assigned to one school.

While Wallinga enjoys the freedom, she said substitutes do deserve to be a bigger part of school communities and develop relationships with their colleagues and students.

“Substitute teaching is a job you can disconnect from at the end of the day, which is one of the benefits,” she said. “Not having a community is kind of a side effect of that.”

CalMatters reporter Jeremia Kimelman contributed to this story.