Desiree Garibay used to sleep outside in Redondo Beach. One night in July 2020, she was lying down in a city park and police issued her a ticket.

She missed her court date, and the ticket became a warrant for her arrest. She said she became even more determined to avoid the courthouse.

But on a Wednesday in April – nearly two years after getting the ticket – Garibay stood by while Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Lonnie Smith waved a metal detection wand over her black Selena sweatshirt. Then she walked into what appeared to be an outdoor job fair, with white tents arched over picnic tables.

Cheery nonprofit workers in matching turquoise shirts greeted her and asked if she needed anything. Palm trees swayed in a breeze from the ocean six blocks west.

A judge in a black robe sat behind a courtroom bench, but instead of handing down sentences, she told defendants things like “excellent job,” “congratulations” and “you have so much good news.”

This is still, technically, Los Angeles County Superior Court. Except it’s outside. And, more critically to people like Garibay, 31, the court makes the unhoused defendants a promise: If you show up to court, we will not put you in jail.

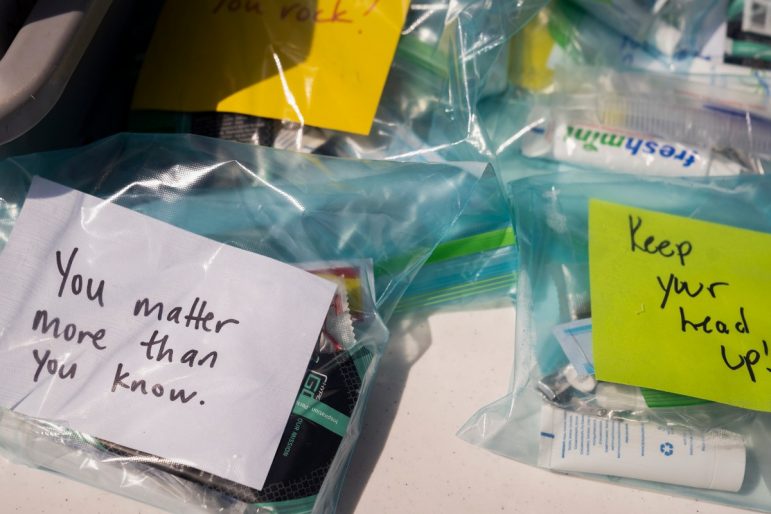

Further, they pledge to help those in attendance get housing. The job fair tents are actually a collection of homeless advocacy organizations, legal expungement teams, mental health and drug counselors, and housing assistance groups.

California already has more than 450 homeless courts across 19 counties, but the Redondo Beach court organizers say their model works better. Here, court convenes in a central location where the unhoused tend to congregate – in this case, close to a food donation center and two religious homeless outreach organizations.

Now organizers want to take that concept and apply it statewide.

A bill sponsored by Torrance Democrat Al Muratsuchi, AB 2220, would create a homeless courts pilot program, offering grants to counties which can tailor programs to their own communities. Outdoor court in Sacramento in August may be less appealing than a spring beach day in Los Angeles County. But the idea is to help counties take their courts to places the unhoused are more likely to show up, while providing services such as employment assistance and substance abuse recovery.

The specifics of the bill’s funding are unclear. The bill calls for giving the Judicial Council an unspecified amount from the general fund to administer the programs.

“At first I didn’t answer the summons, I got a warrant, and there were old warrants too, three (altogether),” Garibay said.

It’s a familiar refrain to homeless advocates and defense attorneys: One original charge metastasizes into a series of missed court dates, warrants for failing to appear and possible jail time.

But Garibay left court smiling, her ticket dismissed. She also walked away with a lead on a new place to stay.

“The best thing about it, other than bringing it to the community where they are, is that a lot of what we do in California for the homeless is in silos,” said Redondo Beach City Attorney Mike Webb. “We bring it all in one place.”

From all outward signs, the homeless court appears to be working. Attendance is far from perfect, but it’s much higher than what homeless courts typically drew when the court was held at the county courthouse in Torrance, Webb said. Statistics provided by the city of Redondo Beach show monthly attendance between 68% and 100%, for an average of 80% attendance since the court moved outside in September 2020.

Webb is the public face of the program, testifying twice at the Capitol, and said the court’s encouraging attendance statistics were a combination of design and circumstance. The court only moved outside because of the pandemic.

“I wish I could say we masterminded it, but really, the pieces fell into place and it became something that worked,” Webb said.

“In my 35 years of working in criminal justice, I have not seen anything (else) where the interests of everyone align.”

Previous attempts at statewide homeless court programs have failed. A 2002 proposal to create a homeless court pilot program in four counties was vetoed by then-Gov. Gray Davis, who cited the bill’s proposed costs against the state’s $24 billion budget deficit.

A 2013 bill that would have encouraged counties to make homeless courts more accessible was set for a hearing in the Assembly Judiciary Committee but was postponed and never heard.

Muratsuchi pitches the courts as an alternative to the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Courts proposed by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Newsom’s proposal would mandate that all 58 counties create courts that could compel people with serious mental illness into treatment. They would not need to be homeless to participate.

The proposed CARE courts faced criticism at their first hearing in late April from mental health advocates and some Democratic legislators, who singled out the proposal’s language permitting the courts to involuntarily commit unwilling defendants into mental health treatment.

“We’re seeing that there was a lot of pushback on the CARE courts,” Muratsuchi said. “While debates are ongoing, the Legislature and the governor should keep in mind this tried and proven model of homeless courts.”

Muratsuchi said the “critical difference” between CARE courts and the Redondo Beach model is that the latter won’t force defendants into mental health treatment.

His bill passed unanimously in the Assembly Judiciary Committee last month, and received one vote in opposition in a subsequent hearing in the Assembly Health Committee.

That opposing vote, from Placerville Republican Frank Bigelow, is rooted in an analysis from an Assembly Republican Caucus consultant who warned members that the courts could allow pretrial diversions for any felony, said Hannah Ackley, Bigelow’s chief of staff.

Ackley said that diversion programs for mentally ill defendants, for instance, don’t allow for pretrial diversions for serious felonies, including murder. She said the consultant report is not public.

“Our consultant suggested the bill would be supportable if it were amended to include the same limitations for homeless suspects that would also apply to mentally ill defendants,” Ackley said in an email to CalMatters.

Muratsuchi told CalMatters he’s planning to change the bill’s language around felonies.

The courts are already enmeshed in the ongoing public debate over Prop 47, a 2014 law that reclassified several property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors and sunsets in November.

A team from the Los Angeles County public defender’s office attends the homeless courts specifically to help defendants expunge their criminal records.

One of the team’s principal duties at the Redondo Beach court is helping reclassify convictions – which were felonies before Prop 47 passed in 2014 – to misdemeanors.

That, said Los Angeles County Assistant Public Defender Tom Moore, is key to helping get defendants housing.

“One of the biggest obstacles to housing is a felony on your record,” Moore said. “We frequently come across clients who don’t know they can have those felonies reclassified.”

Garibay said she has moved in with her boyfriend in Torrance, but is still looking for a permanent place to stay.

“They actually work with you,” she said. “I like just the fact (that) they’re helping me with housing, just my own place finally to call home.”