At a New York gallery in 1980, the artist Alice Neel unveiled a portrait of herself holding a paintbrush and sitting in front of a canvas while completely nude.

Neel’s brave and unflinching self-portrait as a 80-year-old woman stripped to her essence reflects the direct and unsentimental way she painted the scores of people who sat before her easel over the decades: unvarnished, sometimes raw, yet always fully human. The painting is one of more than 100 works spanning the arc of Neel’s career in “Alice Neel: People Come First,” a major retrospective on view through July 10 at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the exhibition is making its third and last stop at the de Young, which is also its only West Coast venue. It spans Neel’s artistic life from her post-art school efforts in the 1920s to the abbreviated yet intense portraits of family members she painted before her death at the age of 84.

The comprehensive exhibition portrays the artist as blazing her own creative trail outside of the mainstream art world while remaining fully aligned with the progressive political values she embraced and the people she championed. They include the residents of the New York City neighborhoods where she lived, political activists, queer creatives and intellectuals, musicians and thinkers, and her own family.

“This exhibition positions Neel as one of the 20th century’s most radical painters — one who championed social justice and held a long-standing commitment to humanist principles that inspired both her art and her life,” said Thomas P. Campbell, director and CEO of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, at a recent press conference.

Neel’s fascination with people — emphasized in the exhibition’s title — is apparent from the first gallery. A wall-sized reproduction of a black-and-white photograph taken by her one-time partner, the filmmaker and photographer Sam Brody, shows a younger Neel surrounded by portraits.

Sitting cross-legged on the ground, she looks at the camera with a distant gaze as a mass of painted faces loom all around her. The haunting image hints at the artist’s obsession with painting people and how deeply she immersed herself in the creation of her pictures.

Neel’s own description of painting her subjects is psychologically intense: “I go so out of myself and into them that after they leave, I sometimes feel horrible — I feel like an untenanted house,” she once told an interviewer. “I have been living in them for two hours, so to go back to myself is sometimes difficult.”

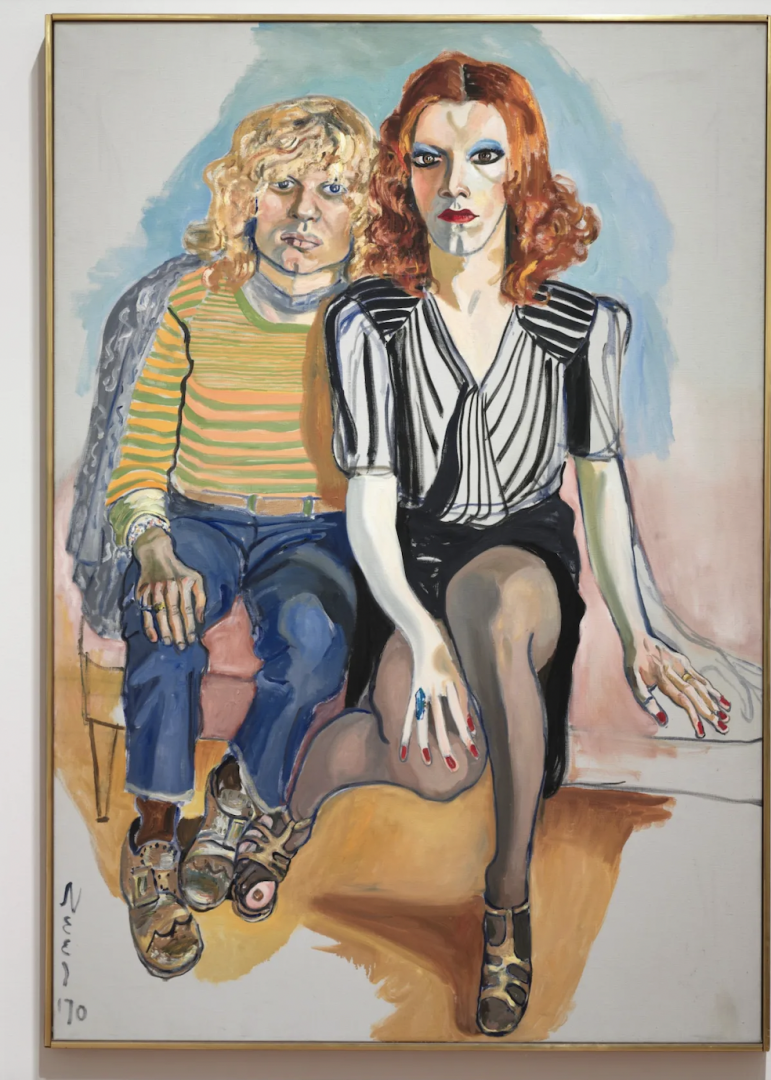

Looking at her dazzling “pictures of people” — as Neel preferred to call them — it’s no wonder the artist lost herself while painting. Whether her subject was one of the children who lived in her neighborhood in Spanish Harlem, or a flamboyant Andy Warhol “superstar” like Jackie Curtis, Neel had a gift for choosing fascinating sitters — and depicting them in sometimes provocative ways.

In one painting, feminist artist and activist Irene Peslikis stares at the viewer, her face framed by dark wavy hair as she flaunts an unshaven armpit and drapes a leg over the arm of her chair. In another, Life magazine editor David Bourdon and his friend, art critic Gregory Battcock, are a study in contrasts: The bespectacled Bourdon is outfitted in a suit; Battcock is pictured in a white tank top, orange socks and banana-yellow colored briefs.

Neel’s subjects display a range of human emotions. Neighborhood children are wistful, weary and sometimes defiant; pregnant women and mothers are knowing and wide-eyed as they cradle and nurse their children or display their swollen bellies.

Neel’s preoccupation with the portrait is evident from the earliest works on display, which include a picture of a young woman painted in a loose Impressionist style inspired by the American artist Robert Henri. There’s also a portrait of Neel’s husband, the Cuban painter Carlos Enríquez, with whom she had two daughters. Her estranged marriage to Enríquez, and the subsequent death of one daughter (and separation from the other), inspired some of the most harrowing paintings in the show.

Neel didn’t flinch from depicting pain, psychological breakdown and even death in her art as she faced so much of it herself. Paintings from the 1920s and ’30s capture the dark colors and somber tones of the Great Depression and the second World War. There are paintings of lovers and love affairs, nightmarish baby clinics and even a suicide ward.

As she grew older, had other relationships, more children and continued to paint even while fame eluded her until her breakthrough show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974, Neel’s art became more saturated in pure color and more sparse as she focused on capturing the essence of her subjects.

Neel once told an interviewer that whether painting or not, “I have this overweening interest in humanity. Even if I’m not working, I’m still analyzing people.”

It’s tempting to think that even at the end of her long life when she was no longer able to paint, Neel was doing just that.