The fourth floor of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art houses a flurry of American Abstract Impressionists — from Ellsworth Kelly to Cy Twombly to Morris Louis — that jostle for your attention, but it is Agnes Martin who gets her very own room: self-addressed and self-contained. An unassuming alcove at the end of an unassuming wing.

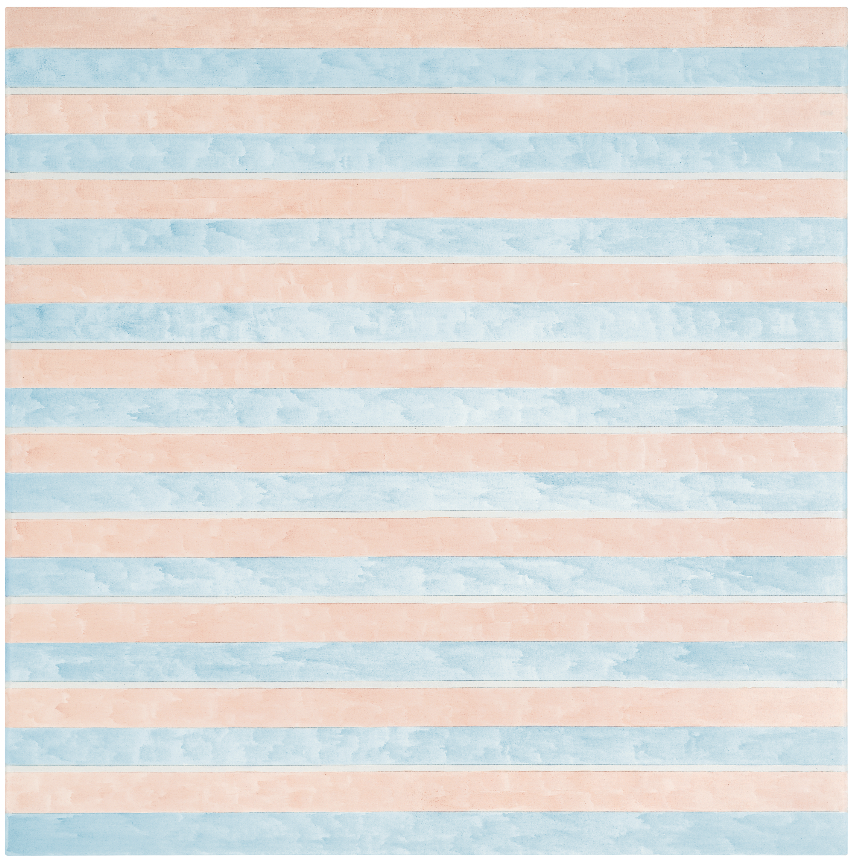

As a general rule, abstract art resists description, and Martin’s works are no different. There’s not much point in trying to put to words what they look like: The paintings are evasive, slippery. What’s to see? A grid laid over a solid color, sometimes three. A lot of almost-sheer pastels, a lot of flaxen yellows and off-whites, the colors you’d catch looking up at your ceiling, mid-yawn, on a lazy Saturday morning, sleep still in your eyes. Maybe you had gone out with friends last night, and despite the slight hangover grating your skull, you’re happy for the memories. Or maybe not. You don’t quite remember, but that’s all right. The elation remains. In a way, this is precisely the hazy moment Martin is trying to capture: “If you wake up […] feel very happy about nothing, no cause, that’s what I paint about.”

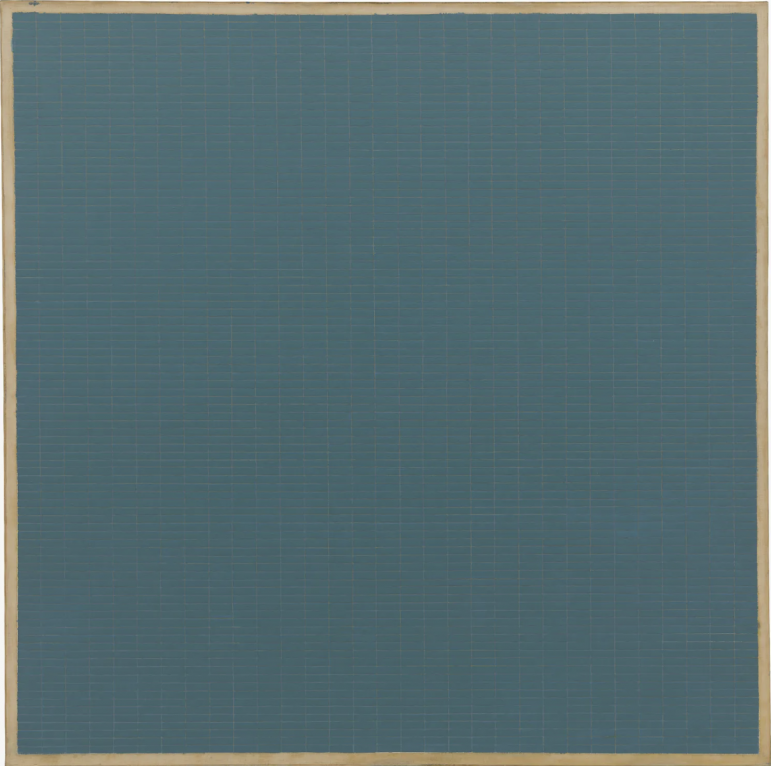

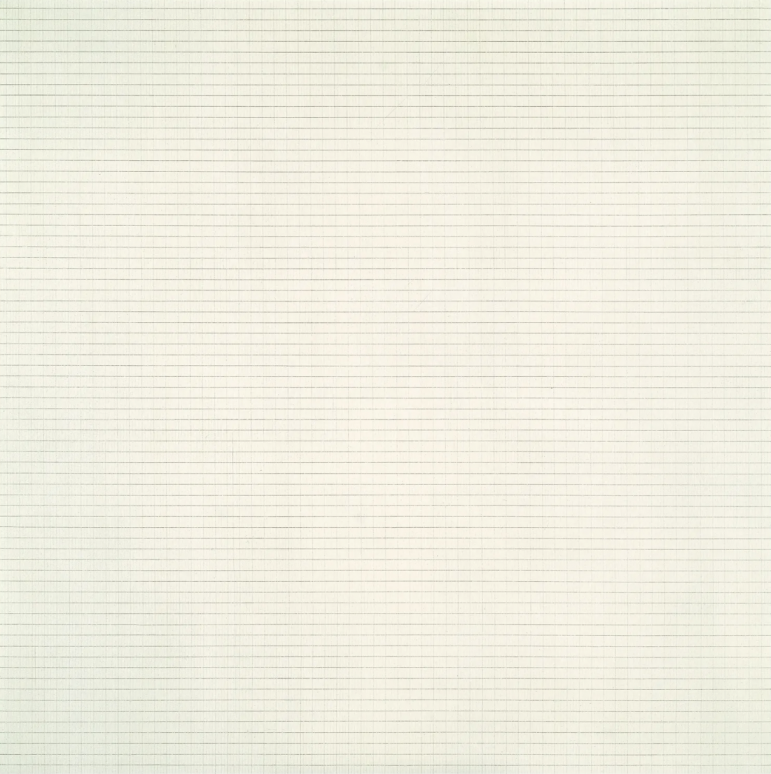

Take “Night Sea” (1963): a solid wall of murky cobalt latticed with a near-invisible web of white. Or is it? Simplicity belies its profundity. The more time you spend staring at the canvas, the more it shimmers to life. Waves undulate, and the “sea” pushes towards you, the viewer, bursting through the delicate warp and weft of what looks like a fisher’s dragnet. Is the threading meant to catch marine animals? Or the viewer? Martin declines to answer. Her painting is strangely potent for having such a simple composition. “Drift of Summer” (1965) follows a similar pattern: off-white background and a grid.

If Martin’s works appear monotonous or visually uniform, it’s because she destroyed most of what she created early in her career. She was a perfectionist, and anything that didn’t meet her strict aesthetic standards went up in flames. Nothing stood a chance: not only paintings but also the “oil portraits, watercolor landscapes, biomorphic abstract paintings and sculpture” that she experimented with before she found the grid.

The grid, the grid — Martin’s singular devotion to it bordered on zealotry. She painted on 6-foot-by-6-foot canvases for 35 years and etched horizontal lines into her paintings for 40 years. (Near the end of her life, she downsized to 5-by-5 canvases only because she couldn’t wrangle the unwieldy 6-by-6 anymore.) The sizable canvases convey a warm largesse that, as Martin put it, invites the viewer to “step into” a work and let emotion engulf you.

The word “fixation” comes to mind, too, but perhaps Martin’s one-track mind is best explained by her training and personal philosophies. Martin studied Zen Buddhism and learned from the artist Ad Reinhardt about Eastern philosophies, so she would likely have been familiar with the Buddhist precepts of khanti (forbearance), dhyāna (meditation), and vīrya (diligence). With its attendant connotations of tolerance, patience, and restraint, “forbearance” elegantly summarizes so much of the force that lies beneath Martin’s work. She often waited, sometimes for months at a time, for inspiration to strike before she put brush to canvas. Once she clocked in five months of patient anticipation before an image materialized in her mind’s eye. These things just take time. And so she would wait.

In her early shows, Martin exhibited with Minimalists, a decision she came to regret as audiences assumed she subscribed to the movement’s emphasis on emptiness and ego death. Martin found Minimalism to be too sterile and evacuated of the puerility and verve she sought to capture in paint. Instead, she chose to align herself with Abstract Expressionism. After all, she wasn’t after a “fact” as much as a feeling — or, in her words, the “subtle emotions” that seem “without cause in this world.” Hence the prosaic yet profound titles she tended to give her paintings: “Friendship” (1963), “Faraway Love” (1999), or “Perfect Happiness” (1999).

Agnes Martin grew up on a farm in rural Saskatchewan, Canada, where the province’s open prairies and boreal forests appear to have left an impression on her aesthetics: an earthly color pallet; flat, geometric compositions; enormous canvases. She was the daughter of Scottish homesteaders, themselves the descendants of Scots who left the Highlands for Macklin, a tiny hamlet on the border with Alberta. After the death of her father — Agnes was 2 at the time — her mother, Margaret, moved the family to Vancouver. The death embittered Margaret, who resented her relegation to single-motherhood and took her frustration out on Agnes. Their relationship strained.

“She hated me,” Agnes recalled. “She loved seeing people hurt.”

Never much of the nurturing type — more of a virago, really — Margaret neglected her daughter, and Agnes ended up spending a great deal of time alone. The solitude nurtured her independence, self-sufficiency, and know-how. She wore these attributes like a badge, a hard-earned reward that she’d come to rely on throughout her life.

As a young woman, Agnes split her time between the Columbia Teaching School in New York City and Taos, New Mexico, declining to fully immerse herself in the New York art world until fairly late in her life. She only got her first solo show in her mid-40s.

At 35, Martin received a scholarship to attend the University of New Mexico’s art program, which “at that point” boasted what one filmmaker labeled “one of the most innovative and creative departments in the United States.” The following year, she enrolled in the department’s summer program and thus began a multiyear stint as an instructor at the university. Eventually, she caught a break and, at the behest of the famed gallerist Betty Parsons, Martin packed up her life in Taos and moved to The Big Apple in 1957.

In Manhattan, poverty destabilized her and chewed away at her sanity, but she got by, thanks to a string of odd jobs, the generosity of her partner, Mildred Kane, and a network of close friends. Martin lived in an apartment on the southernmost edge of Manhattan on the island’s bustling Financial District, overlooking the East River, in the neighborhood of Coenties Slip: where stevedores unloaded barges day in and day out on this inlet in 18th and 19th century New York.

By the 1960s, though, the dockworkers were gone, replaced with a gang of young artists. This small community wasn’t quite “derelict,” but it wasn’t far off. Sunlight leaked into Martin’s apartment through the rafters in her ceiling, which was never properly sealed. A heater took the chill out of the air, but it was still frigid. So was her studio.

Nonetheless, Martin enjoyed much of her time in New York. Rent set her back a bargain $45 a month (about $400 today), and owing to these cut-rate living expenses, a slew of cutting-edge artists shared this sliver of idyllic South Manhattan with her: Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman.

Martin names each of these men in an interview with filmmaker Mary Lance for the 2002 documentary, “With My Back to the World,” released two years before Martin passed. Conspicuously absent from this list, however, are two women — Chryssa, a light sculptor, and Lenore Tawney, a textile artist — with whom Martin was romantically involved. Perhaps this is an innocent and inadvertent slip-up, a result of her nonagenarian memory losing its acuity. Perhaps, though, Martin’s choice to let the names of her ex-lovers slip into oblivion speaks to the level of anxiety she carried over her career as a woman who loved women.

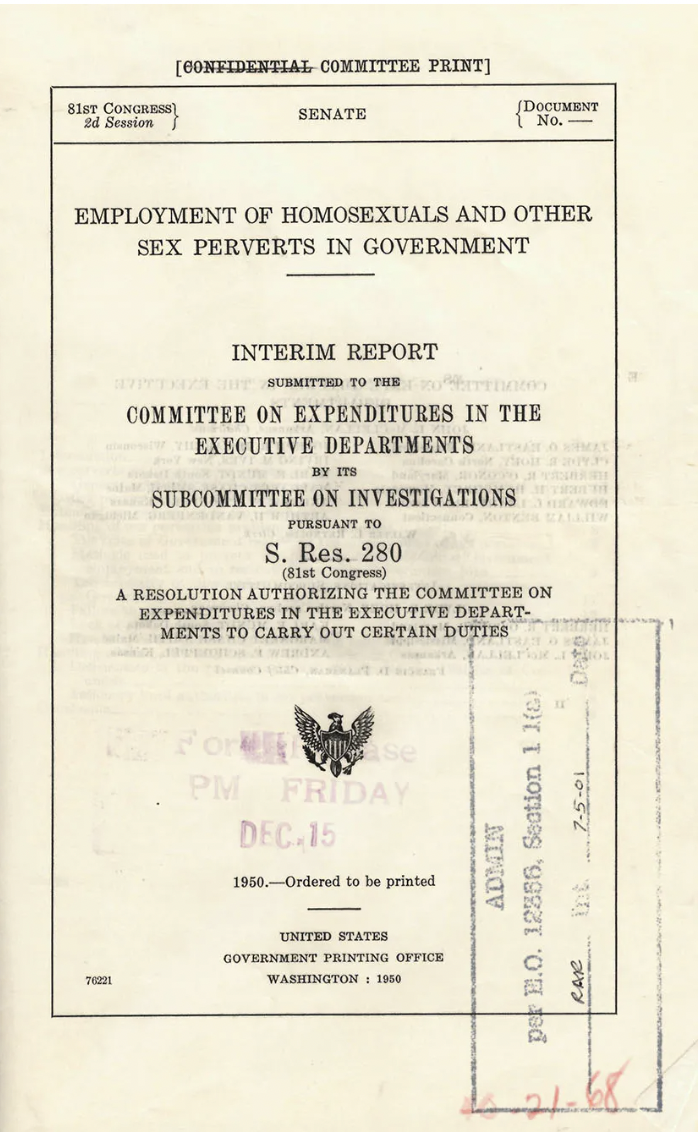

Martin was closeted, yes, but biographies suggest she didn’t refuse the label “lesbian” offhand. Instead, like the German actress Marlene Dietrich, Martin immersed herself in the underground gay scene while also maintaining plausible deniability for safety’s sake. Lest it be forgotten, homosexuality in mid-century America carried incalculable risks. This was, after all, the era of the Lavender Scare, a government sanctioned witch hunt of homosexuals that borrowed from Senator McCarthy’s Red Scare playbook: Whip up a moral panic, point a finger, persecute, repeat. Gays and lesbians were gaining a degree of visibility in public life, but with that visibility came growing anxieties about deviancy that ignited a vicious campaign of homophobia.

So it shouldn’t come as a great surprise that paranoia choked Martin: She was terrified of losing funding and, thus, economic security because of her sexuality. In this atmosphere, Martin would remain in the closet. End of discussion.

Martin’s budding fame tortured her. Years of poverty had taken its toll, and the wear and tear of rough living was beginning to catch up to her. Martin had exhibited symptoms of schizophrenia years earlier, but, like her sexuality, she kept her struggles and eventual diagnosis a guarded secret. Compounded together, her precarious financial situation and struggles with mental health periodically hit a breaking point. Her mind would betray her and unravel.

She suffered a number of psychotic breaks over her career, often admitted to New York’s Bellevue Hospital, a free clinic where, according to the artist Kristina Wilson, “all the indigent people [went] when nobody [knew] what else to do with them.” Bellevue garnered its own kind of cult infamy. John Lennon’s assassin was treated there. So was Norman Mailer after he stabbed his wife. The Beat poet Allen Ginsberg name-checks the hospital in his 1956 poem “Howl.”

After a particularly debilitating spell of psychosis in 1967 — she couldn’t even remember her own name or address — Martin ended up in Bellevue, where she was bedridden. She had been found roaming the streets of New York, disoriented, allegedly for nine days. Her amnesia proved problematic, as Martin couldn’t contact anyone from her network for help.

Were it not for a stroke of luck, though, Martin might have fallen through the institutional cracks of the mental hospital, left forgotten and unclaimed. A nurse happened to find a piece of paper in Martin’s pocket with a phone number on it. It turned out to belong to her friend and fellow artist Robert Indiana who rescued her and, with the help of her lover, Lenore Tawney, got her private psychiatric care. (Tawney footed the bill personally.) As the treatment took hold, her addled mind finally relented.

Psychiatric medicine of the day held little respect for the rights of patients, much less the uninsured experiencing acute psychosis. Martin claimed medical staff at Bellevue subjected her to electroconvulsive therapy more than 100 times and manacled her using a four- or five-point restraint system, now considered an intervention only of last resort that fully immobilizes a patient. Originally, this method of physical restraint was intended for swift intervention during moments of severe distress or convulsion, but groups like Human Rights Watch have since pointed out a troubling pattern of abuse facilitated by the system. (The American Academy of Nursing has even called for completely abandoning the use of restraints on older patients.)

I mention all this because, from the perspective of Martin’s mental health, the grids she so favored start to resemble the grates of a jail cell. Her hospitalizations were a form of incarceration, but so, too, was her stardom in the art world. At some point or another, it appears as though her fame began to feel carceral, imprisoning her in a world that she felt more and more estranged from.

“I suddenly felt I wanted to die,” she said, “and it was connected with painting. It took me several years to find out that the cause was an overdeveloped sense of responsibility.”

Added to ongoing fears of “further incarceration in Bellevue Hospital,” Martin abandoned the New York art scene in 1967 and fled west.

She set out for the mythic American Southwest, leaving one hotbed (New York) for a hotbed of another sort (New Mexico). Along her journey, a return to her old home, she traveled up into Canada and threaded the border region before eventually making her way to a small town in northern New Mexico, where she built an adobe home for herself from the ground up. Life off the grid presented its challenges: Sometimes she lived off the slim pickings of cheese, walnuts, and preserved tomatoes she grew herself while dealing with periodic bouts of paranoia and panic, according to biographer Nancy Princenthal. At some point, Martin built a log studio and, soon after, returned to painting.

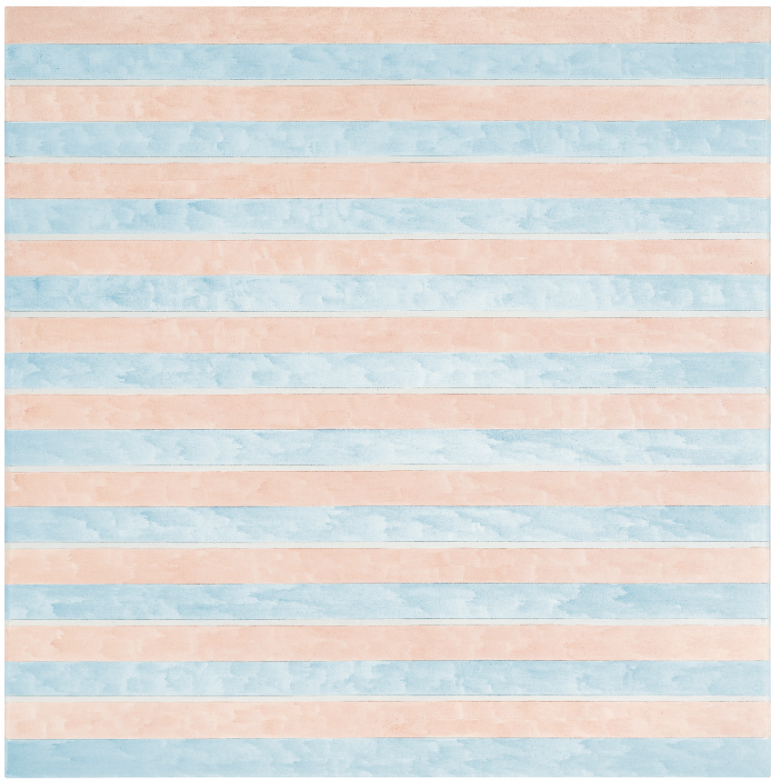

Cages chased Martin throughout her life: The psychiatric hospitals she passed through, the same-sex romances she kindled in a deeply homophobic world and, at one point, the practice of art itself. Yet she never relented in her pursuit of perfection and precision. She continued to paint and produce some of her most acclaimed works well into old age, works that were exhibited across the United States and Europe (the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Serpentine Gallery in London, the 1997 Venice Biennale). The SFMOMA collection counts three paintings from this period: “Untitled #9” (1981), “Untitled #5” (1988) and “Untitled #9” (1995).

In these later years, Martin reconnected with old friends and found more balance in her life in New Mexico. In the early 1990s, she moved to a retirement home in Taos, which no doubt helped ease her through senescence. Word of her acclaim continued to spread: She was awarded a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 1997 and a National Medal of Arts award from the Clintons. Martin would pass from congestive heart failure in 2004 at the age of 92, a giant in the art world.

Over her turbulent and challenging life, Agnes Martin managed to build a remarkable and sizable body of work that continues to resonate with viewers today. I noticed how noisy museum-goers would invariably grow silent in the presence of her paintings. One couple’s conversation slowed to a lull as they, without looking, reached silently for each other’s hands.

Perhaps it’s because of her challenges, and not in spite of them, that these canvases exude the psychic power they do. She pierces to the heart of some indescribable feeling and captures, with unmatched purity, life’s fleeting, innocent and evocative moments on canvas.

An Agnes Martin is sure to surprise you. So take a seat, and let yourself absorb the work. Or maybe, in the end, it’ll be the paintings that will absorb you.

The Agnes Martin collection will be showing on the fourth floor of the SFMOMA indefinitely. The museum is open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Mondays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays and 1-8 p.m. Thursdays. General admission is $25, and the first Thursday of every month is free to Bay Area residents. For more information, visit www.sfmoma.org.

Thank you for this article. I am doing some research on Agnes Martin and Lenore Tawney. Can you verify that Lenore paid for Martin’s psychiatric treatment?

Also where is it verified that they were lovers?

Thank you for your help.