Maggie Cao is the David G. Frey Assistant Professor of Art History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

I doubt that even Netflix expected “Is It Cake?” to be such a hit.

The premise, if you haven’t already binged the TV series, involves professional bakers trying to fool judges by creating cakes that don’t look like dessert but instead appear to be everyday commodities – purses, toys, fast food.

But while most critics see this as just another iteration of mindless TV, I see “Is It Cake?” as deeply tied to a cultural moment in which deception – and learning how to recognize it – has become a part of everyday life.

A show like “Is It Cake?” offers a safe way for viewers to test their capacity to spot a fake. This may seem like a stretch; cake and conspiracy are hardly the same thing.

Yet as an art historian who researches the history of visual deception, I’ve noticed that throughout American history, moments of social anxiety around truth tend to be accompanied by similar “fool the eye” pop culture phenomena, from P.T. Barnum’s hoaxes to a painting technique called “trompe l’oeil.”

Guessing games

In the last decades of the 19th century, while the art world was enamored with Van Gogh and Matisse, middle-class Americans became obsessed with trompe l’oeil paintings – hyperrealistic still lifes that featured life-size everyday objects. They looked so real that people reportedly tried to grab painted violins and dollar bills off the wall.

Even those prone to suspicion could fall victim, because the paintings were exhibited without frames and in atypical settings like pubs, shop windows and hotel lobbies. In these quintessential urban public spaces, the act of being fooled became a collective social experience, much as it is on “Is It Cake?” Not only are viewers taking pleasure in the failure of the on-screen judges, but the judges themselves must also reach a collective verdict after 20 seconds of debate.

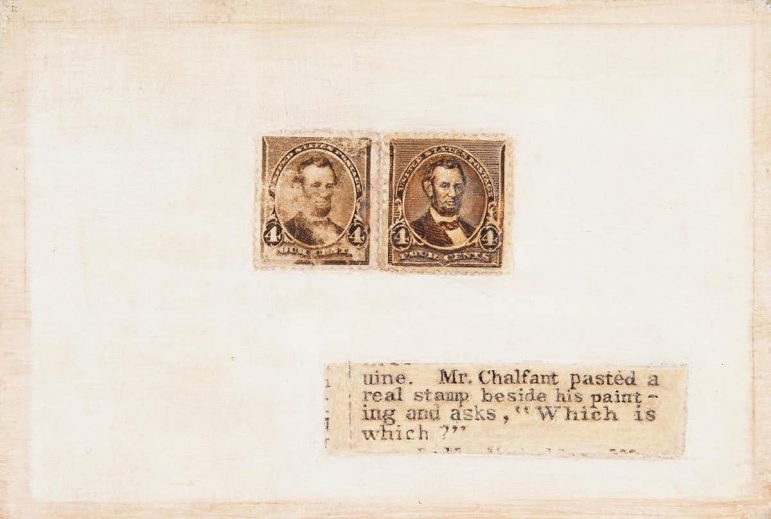

One particular 1890 painting of stamps is remarkably reminiscent of a bit called “Cash or Cake” that closes out each episode of “Is It Cake?” The painting, by Jefferson Chalfant, unassumingly features two Lincoln stamps side by side, one painted, the other real. Below them, a painted news clipping invites viewers to decide which is which.

On the show, the winning baker faces this exact predicament when offered the opportunity to win bonus prize money: Guess which of two containers overflowing with cash is actual money, and which is cake. The point of the confounding exercise is to show that even the most talented illusionists can be made the fool.

Self-conscious humor was also central to trompe l’oeil. Rather than signing their names as artists are apt to do, trompe l’oeil painters often painted their own photographs or letters addressed to their studio into their still lifes as an inside joke.

In the past, what fascinated Americans about trompe l’oeil was not just that they could be tricked by talented artists, but the how and why of their deceptions. The Secret Service questioned one painter named William Harnett after he painted a wrinkled five-dollar bill.

Another, John Haberle, had one of his paintings forensically examined by a panel of experts who observed it under a lens and even rubbed off some of the paint.

This investigative penchant explains the curious genealogy of “Is It Cake?” The show traces its roots to a series of viral Instagram videos from 2020 that featured illusionistic cakes at their moment of denouement.

Most viral videos don’t become television series, but this one has because the esoteric process of creating the illusion equally fascinates, even if viewers have no fondant-focused aspirations.

A sugary allegory

Trompe l’oeil is an ancient art form, but it exploded in the United States, and nowhere else, in the 19th century because deception was a new and particularly American problem.

Cities and industries were growing more rapidly than ever before, and many Americans moving from rural areas faced urban anonymity for the first time. Cities were rife with crooked opportunists, from con artists to counterfeiters – the Anna Delveys and Tinder Swindlers of their day. Trust was a tricky matter.

In this milieu, trompe l’oeil had a social function. It gave Americans an outlet for testing their discernment in a manageable and pleasurable way.

So it doesn’t surprise me that the gravitation toward a show like “Is it Cake?” is happening at a time when more ominous deceptions lurk in the media landscape. There are even moments when the show veers in darkly suggestive directions. In one episode, the bakers collectively try to educate host Mikey Day by teaching him the term “tiltscape,” which, they explain, has to do with the balance and weight distribution of baked goods. After Day uses the word in his appraisal of the contestants’ work, they later reveal that the term was a hoax all along – a sugary allegory for socially fueled misinformation.

At a time when we often don’t know if what we encounter on our screens can be trusted, it feels good to alleviate those anxieties with a show in which the only consequence of being fooled is cutting into a shoe that we assumed was a cake.