For the first time since the start of the century, California has fewer than 6 million students attending public schools.

According to new data released by the California Department of Education, enrollment in public schools continues to drop more quickly than it did before the pandemic, stirring fears of more budget cuts and long-term financial instability for schools.

Among key takeaways from the newly released data:

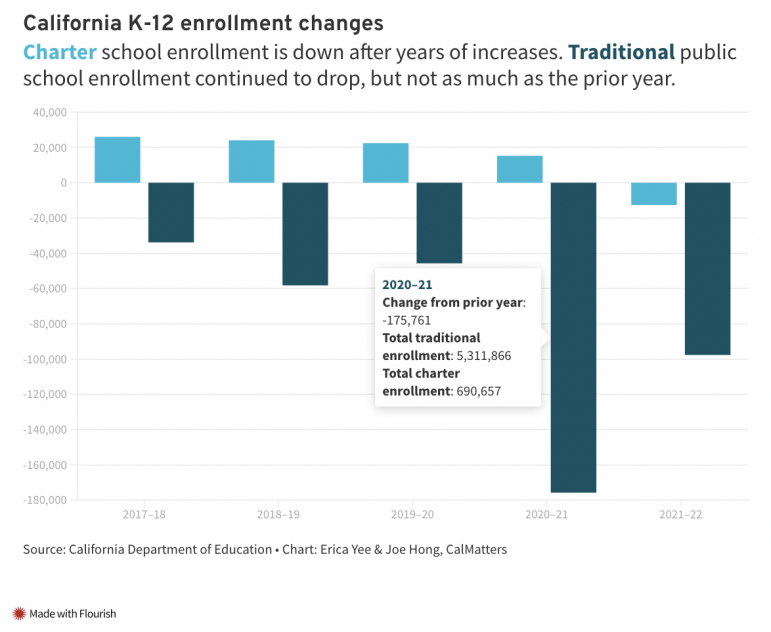

- Statewide enrollment has dropped by more than 110,000 students to 5,892,240 during the current school year, a 1.8% dip from last year but less steep than the 2.6% decline during the first year of the pandemic.

- Charter school enrollment also is down for the first time since at least 2014.

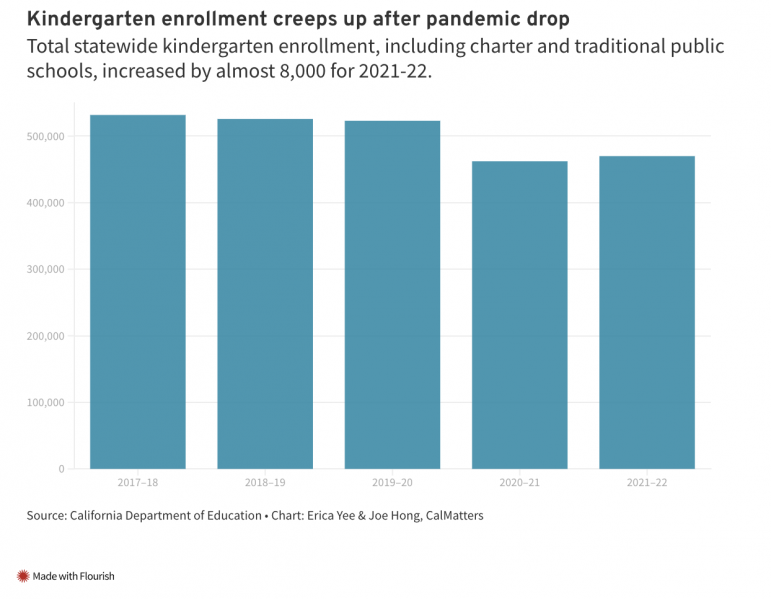

- Kindergarten enrollment is up, though nowhere near pre-pandemic levels.

- And 9,000 more students are enrolled in private schools, a 1.7% increase, but that doesn’t explain much of the exodus from public schools.

For the better part of a decade, public school enrollment was in steady decline in California mostly due to a lack of affordable housing, education officials across the state said. When the pandemic reached California, early job losses collided with that trend, making the decline worse.

Richard Barrera, a board trustee at San Diego Unified, the state’s second largest district, said families were moving out of the district, especially those in gentrifying areas, resulting in disproportionate losses for schools in those neighborhoods. Then workers started to lose jobs in 2020, and more families had to relocate.

“When we opened up the schools last year, those schools had lower in-person attendance,” Barrera said. “It’s just more expensive for people with kids to live in California.”

In the years before the pandemic, enrollment in traditional, non-charter public schools fell by about 1% a year. The first year of the pandemic, however, enrollment dropped by more than 3%, or about 175,000 students.

Even charter school enrollment slid, losing 12,600 students this year, a major reversal of historical trends. Since 2015, charter schools have seen only increases each year of at least 10,000 students.

Officials at the California Department of Education did not have a clear explanation for this sudden drop.

The California Charter Schools Association President Myrna Castrejón said this decline illustrates how charter schools “are facing the same statewide challenges as non-charter public schools.” She called for equitable funding for charters.

For non-charter schools, much of the enrollment drop during the first year of the pandemic was due to tens of thousands of parents opting not to enroll their children in kindergarten. Most school campuses were closed at the time and children were learning online.

This year, with school buildings open, kindergarten enrollment went up by more than 7,000 students, recovering slightly from last year’s 60,000-student plunge.

Enrollment numbers for first graders, however, dropped by 18,000 students this year — one of the steepest drops for a single grade level — suggesting that many students who were of kindergarten age in 2020 did not return to public schools for first grade.

California Department of Education officials would not comment on where those students went. Some school district officials said they also are looking for answers.

“It’s a problem across all grade levels,” said Barrett Snider of Capitol Advisors, a lobbying firm for school districts. “We just aren’t sure where they’ve gone.”

Because most of California’s public schools are funded based on a combination of enrollment and attendance, small school districts are especially feeling the pain. Just a few students leaving can mean large chunks of money gone from their budgets.

“We’ve had declining enrollment since the turn of the century,” said Linda Irving, superintendent of Sebastopol Union School District. “As a school gets smaller, it gets more difficult to provide quality programming, like music classes.”

The 788-student district has been using one-time state grants to cover its costs, Irving said, but she needs a more permanent solution.

It can be depressing working at a school where the student population is shrinking, she said. Administrators have a marketing budget to attract more families, yet they are being forced to cut staff.

“I was driving home from the gym yesterday, and I heard another superintendent on the radio,” Irving said. “We’re competing against each other.”

Brett McFadden, superintendent of the Nevada Joint Union High School District, said a large portion of the residents in his rural community work in the service industry and had to seek other jobs when businesses closed during the pandemic. Others left more recently, as the state began enforcing masking rules and issuing vaccine mandates.

“It’s tough to do exit interviews, but our takeaway is that people left because of jobs,” McFadden said. “Or they left because private schools weren’t enforcing mask mandates.”

According to state data, Nevada Joint Union High’s enrollment was stable before the pandemic at around 2,800 students. As of Friday, McFadden said, enrollment is at 2,605. He said he lost 197 students since the school year started, which translates to more than $2 million in lost funding.

“Declining enrollment cannot be fixed,” he said. “I think we have to recognize that declining enrollment is part of broader demographic trends that are happening in our state.”

Softening the blow

State leaders are floating measures to lessen the pain of declining enrollment.

In his proposed budget, Gov. Gavin Newsom said he would allow school districts to use a three-year average attendance rate to calculate next year’s funding. This could be a substantial help, especially because attendance at most schools plummeted during this year’s omicron surge.

State Sen. Anthony Portantino, a Democrat from Glendale, authored Senate Bill 830, which would pay districts based on enrollment rather than attendance.

While the policy debate over enrollment versus attendance-based funding has been ongoing for years, Portantino said this is the right time to make the change because of the state’s surplus and the acute crisis of plummeting attendance and enrollment.

“School districts have to budget based on enrollment,” Portantino said. “It makes no sense to penalize them if you have absences throughout the year.”

Under his proposal, districts would still be funded based on attendance but could apply for additional money based on enrollment. The bill would require that districts use 30% of the additional funding to address chronic absenteeism.

While these proposals might ease the fiscal effects of ebbing enrollments, district leaders still don’t have a clear picture of why so many students are leaving. And they feel powerless to reverse the trend.

“Schools have been reacting to a public health crisis and trying to keep their lights on, so when kids disappear there’s not a lot of capacity to chase them down and see what happened,” said Snider, the lobbyist. “But I think that’s going to be a big focus as we climb out of this.”