In the push to screen all California students for dyslexia, some worry English learners will be mislabeled, making it harder for them to become fluent in the language.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has set aside millions over the past two years for dyslexia research at University of California San Francisco to create screening tests in multiple languages that would signal if a child is at risk for dyslexia. A bill in the state Legislature would require all kindergartners, first graders and second-graders to be screened for dyslexia starting in the 2022-23 school year.

But the idea of a universal dyslexia screening test concerns some teachers and researchers who advocate for English learners. They say tests must be carefully designed to avoid misdiagnosing students who are learning English.

“As a reading specialist, I think we need to exercise extreme caution so as to not create a policy that is potentially detrimental to historically marginalized groups of students,” said Lillie Ruvalcaba, English learner teacher on special assignment in Mountain View School District in Los Angeles County.

“As a child who was an English learner, I’m saying slow down.”

Currently, dyslexia assessments are not mandated. Schools often test students for reading disabilities only if parents or teachers believe they may have one, and often these tests don’t happen until students are in third grade or older.

Advocates for English learners say any screening must be designed with the students’ native languages and cultures in mind. Typically, students who are found to be at risk for reading disabilities are pulled out of the classroom to work with a reading specialist. Advocates say reading interventions for students who are learning English as a second language need to be specifically designed for them.

“Blanket implementation of reading programs designed for native English speakers without considering effective literacy for emergent bilinguals – it’s a recipe for once again mis-serving and leaving English learners behind,” said Martha Hernandez, executive director of Californians Together, a coalition of organizations focused on improving education for English learners.

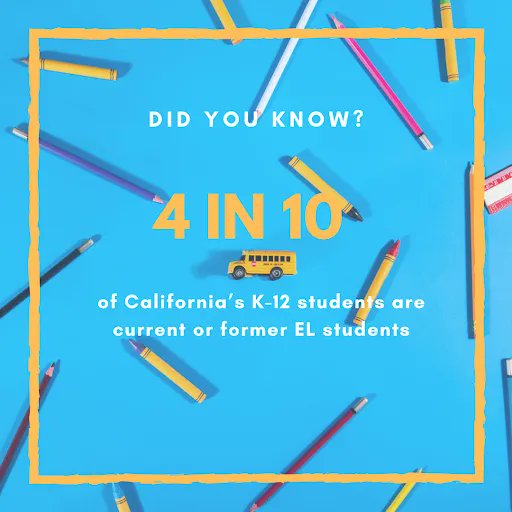

There are more than 1 million English learners in California public schools. The vast majority – 82 percent – speak Spanish, 2 percent speak Vietnamese, 2 percent speak Mandarin, 1.5 percent speak Arabic, followed by at least 70 other languages, according to the California Department of Education.

Research shows that some English learners are inappropriately placed in special education classes. At the same time, many English learners who do have learning disabilities are identified later than their English-speaking peers.

Hernandez and many others opposing the screening are not yet familiar with the assessment tools being developed in English, Spanish and Mandarin by UCSF. The tools have been partially funded by the state of California, and UCSF plans to make them available to all school districts for free. If the Legislature makes it mandatory for all districts to screen students for dyslexia, this would be one tool that could be used.

Lillian Durán, associate professor in the Department of Special Education and Clinical Sciences at the University of Oregon, is leading the team at UCSF in creating the tool in Spanish.

“What we’re trying to do overall is provide teachers with more meaningful information from these assessments. I think assessments end up getting a bad name because in the past they have provided very little data that actually helps,” Durán said.

Durán, who grew up in San Francisco, said the assessment is being designed in Spanish, not just translated from English. For example, the measure includes frequent words in Spanish-language children’s books and curriculum, not simply words translated from the English tool. It also includes a measure of how well the child reads syllables, because if a child is learning to read in Spanish, they would more often learn to read syllables, rather than individual letter sounds.

She said it is important to remember that tests like this are not used to diagnose children with dyslexia, but to flag which students may need extra reading help.

Durán says she hopes to hold focus groups with teachers, students, administrators and advocates for English learners in the spring and summer.

“I really want to make sure the measures are reviewed to make sure they are meeting the needs of the community,” Durán said.

For some educators, the concern that students who speak languages other than English could be misdiagnosed with a learning disability is based in history.

Hernandez has firsthand experience with English learners being mislabeled as dyslexic.

In the late 1970s, she taught in a school in the Goleta Union School District in Santa Barbara County, where about half of the students in her combined fifth and sixth grade class had been labeled as dyslexic. All of them were English learners. Over time, she realized that most of her students did not have dyslexia, but instead were behind in reading because they had not had appropriate instruction in English language development.

A 1973 report by the California State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that Mexican-Americans were disproportionately placed in special education classes in Santa Barbara County at the time. A letter from a school psychologist included in the report justified the disproportionate diagnosis of dyslexia by saying that it had probably been inherited from the children’s parents, who must have “gravitated” toward farmworker jobs because of their reading disabilities.

Ruvalcaba said even in recent years, she has seen schools misdiagnose children with disabilities because they were learning English as a second or third language.

“We’ve seen that that mislabeling can often turn kids off to school. It delays their reclassification to ‘fluent English proficient’ because they’re not in the classroom learning the content or vocabulary they need in order to pass the ELPAC,” Ruvalcaba said. The ELPAC is the English Language Proficiency Assessment of California, a test that all English learners must take every year until they are reclassified as fluent in English.

Dozens of other states already test kindergartners and first graders for signs of dyslexia. Elsa Cárdenas-Hagan is a bilingual speech and language pathologist and president of Valley Speech Language and Learning Center in Brownsville, Texas. She helped design a test used in Texas to help identify reading problems in Spanish, called Tejas Lee (Texas Reads).

“In Texas we have not witnessed an overidentification of children with special education needs, or dyslexia, because they are English learners. It just hasn’t been the case, from 1998 to today,” Cárdenas-Hagan said.

Cárdenas-Hagan said screening tools can help identify potential problems. For example, if a child who speaks Spanish at home and has been taught in Spanish at school doesn’t recognize the letter sounds in Spanish, that may be an indicator of dyslexia.

“If we don’t measure and we don’t do anything about these kids, then they’re going to go without any treatment,” Cárdenas-Hagan said.

Cárdenas-Hagan said she was recently asked to assess a 17-year-old student who had moved from California to Texas, who had dyslexia that was never identified.

“By that time the child feels really bad about themselves. They’re discouraged, right? Their confidence has been really shaken, and they’re not enjoying school and having a love of learning because they can’t read,” Cárdenas-Hagan said.

Some experts in special education for children who speak languages other than English say the solution is more complex than one screening tool.

“Some places over-identify and some under-identify. Some are hesitant to do anything, and some are too eager,” said Cristina Sánchez-López, senior associate at Paridad Education Consulting. “There are some districts that say, ‘They’re English language learners, so let’s just give them time,’” while others rely on screening tools without looking at the big picture, she said.

Sánchez-López co-authored a book with speech-language pathologist Theresa Young focused on effective teaching for multilingual learners with special education needs. They both advocate for a different approach, in which school districts bring together experts in special education and experts in teaching bilingual children. They recommend analyzing data within a larger context, including the language children speak at home, the language they are learning in and what kind of reading and English language development instruction they are receiving.

“As a speech-language pathologist, we see all the screening data, but unless I have someone at the table who has a bilingual and ESL lens and understands the data as well, we tend to interpret those screeners from a monolingual lens,” Young said.

Instead of a universal screening test, Ruvalcaba and others would prefer California invest in better education for teachers on how to teach reading, how to help students who are having trouble learning to read, and how to best teach students who are becoming bilingual in English and their native language.

“In most other states you can major in education, which means you have four or five classes on how to teach literacy,” said Allison Briceño, associate professor and coordinator of the Reading and Literacy Leadership Credential and Master’s Program in the San Jose State University Department of Teacher Education. “I taught in one of those programs, and what my pre-service teachers were able to do was much more sophisticated than here in California, where often they’ll only get one semester of literacy.”

Ruvalcaba agrees. She didn’t feel prepared to help children who were having difficulty learning to read until she participated in a program called Descubriendo la lectura, or Reading Recovery, that helped her learn effective strategies to help children learn to read in Spanish and English. She used the strategies she learned to work with first graders who had not yet learned to recognize letters, and got them to grade level within 10 to 12 weeks. She said other teachers were eager to learn the strategies from her.

“If you want to spend money, don’t give me a universal screener. I already do enough assessment in my classroom,” Ruvalcaba said. “If you want to spend money on making California’s education more valuable, more progressive, more effective, spend that money on teaching teachers how to implement effective strategies.”