Daniel Poulos worked as a custodian for Castro Valley Unified School District for 12 years. He became a familiar face at Redwood High, a school for at-risk youth, where he made sure the classrooms were clean and the lights stayed on.

But in 2017, he got the chance to become a history teacher with the help of California’s Classified School Employee Credentialing Program, where he spent a year earning his teaching credential. That year, California allocated $25 million in grant funding that would help non-teaching school staff become teachers in an effort to address a statewide shortage.

He said he had always expected to retire as a custodian. “But when the opportunity to teach arose, I jumped at it,” Poulos said.

State-funded teacher training programs continue to chip away at the dire teacher shortage in California, but they might not be enough to deal with the urgent, short-term needs.

A January report by the Learning Policy Institute found that some of the state’s largest districts had 10% of vacancies still unfilled at the start of the new school year. One district had a quarter of its vacancies unfilled.

And not all districts are feeling the benefits of the state money. More remote, rural districts don’t have enough applicants for state grants, nor do they have four-year universities nearby to train educators.

“We don’t have time for grant writing,” said Morgan Nugent, superintendent of Lassen Union High. “Our time is stretched making sure we have meals going to kids and educators in classrooms.”

Barret Snider, a lobbyist who represents school districts across California, said that he heard one superintendent compare the state’s grant programs to giving a Disneyland vacation to a family in poverty.

“That’s nice,” Snider said. “But that’s not what we need.”

Since 2015, California has invested $4.8 billion in teacher recruitment, retention and training efforts, all designed to alleviate a chronic staff shortage that devolved into a crisis during the pandemic. That amount of money would pay one year’s salary for over 56,000 teachers earning the average salary for public school teachers in 2019-20. Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed spending $560 million more in next year’s budget.

While school districts consider these short-term grants a blessing, administrators say more permanent increases to education funding are necessary to help them pay the ongoing costs of teacher salaries and benefits. Teacher salaries can range from around $50,000 to about $100,000. One of the bonuses of teaching are the long summer and holiday breaks.

Nicole DiRanna, who oversees a teacher training program at San Marcos Unified in San Diego County, said her district is doing the most it can within the restrictions of this state funding, but the obvious solution is to raise teachers’ pay.

“The problem is the different types of state funding,” she said. “If we had it our way, we would just raise the salaries, right?”

The teacher shortage predates the pandemic.

School districts had a tough time hiring teachers as they began recovering from the Great Recession and reinstating positions that had been cut, according to a 2016 study by the Learning Policy Institute. Science, math, bilingual and special education teachers were in particularly high demand and the study projected that statewide, districts would need to hire about 300,000 teachers a year starting in 2018.

“Prior to the pandemic, big drivers of shortages were significant decline in preparation, increased demand and teacher turnover,” said Tara Kini, the director of state policy at Learning Policy Institute. “In California, that accounts for 90% of the demand.”

While student enrollment also dropped at a faster pace during the pandemic than during previous years, teacher retirements and turnover were even bigger factors at some districts.

Since the start of the pandemic, teachers have been leaving the profession at a faster rate. The California Department of Education does not track statewide teacher turnover, but data from the California State Teachers’ Retirement System shows that retirements increased by 26% in the first year of the pandemic. According to a survey, 56% of retirees left due to the challenges of teaching during the pandemic.

California Teachers Association president E. Toby Boyd in a statement to CalMatters said teachers are “exhausted and burned out and are planning to leave the profession earlier than expected.

“If California is truly serious about providing every child with the education they deserve, addressing our teacher shortage should be the top priority of every district and our elected leaders right now,” he said.

School district administrators and union leaders across California agree that virtual instruction pushed many educators out of the profession for good. They also say teachers have been underappreciated during the pandemic.

“It’s bad, and it’s going to get worse,” said Matt Best, superintendent of Davis Joint Unified School District. “The trend has been in place for a better part of a decade. We have to fix some of these barriers.”

One of those barriers is the cost of becoming a teacher. After earning a bachelor’s degree, prospective educators need to spend an additional one or two years in school earning a credential and spend time as unpaid student teachers.

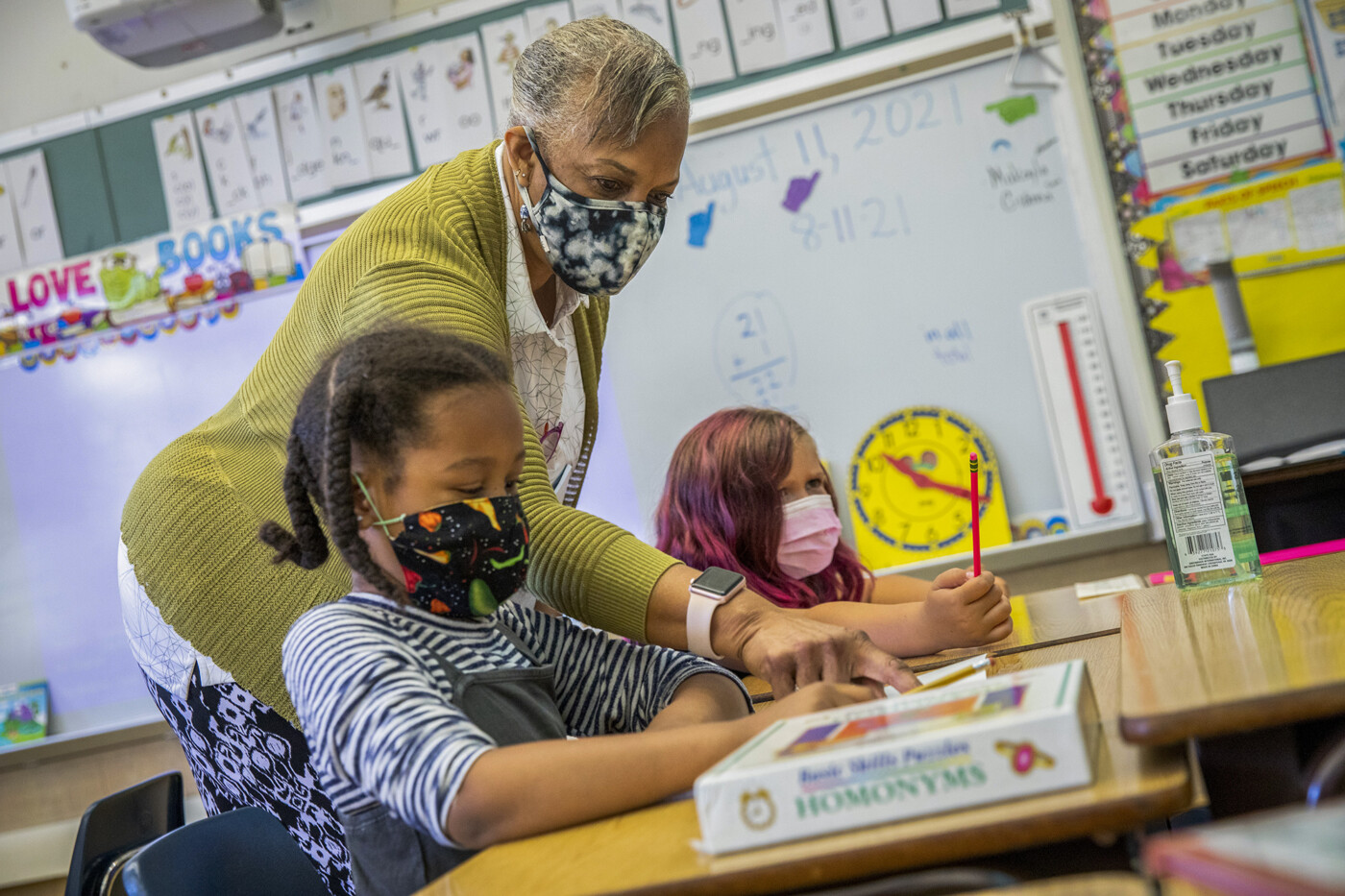

To help ease that burden, California has budgeted nearly $170 million since 2017 to help current public school employees who aren’t teachers earn teaching credentials. They can get up to $25,000 to help cover tuition, books and testing costs. The grants have so far produced 511 teachers and could generate up to 7,620 in the coming years.

At Davis Joint Unified, Best said his goal with this program was to diversify the district’s teachers with a labor force that would stay with the district for many years.

“These were people who were already invested in the community and in their schools,” he said. “The program is attractive to them because they’ve lived here for a generation.”

The state has also offered school districts $350 million for teacher residency programs where college graduates receive stipends and are paired with mentor teachers, who provide hands-on training.

In Fresno County, teaching “residents” work at rural schools while attending classes at local universities. After completing the two-year program, they’ll be considered first for job openings in their districts.

“We need our workforce to mirror our rural community,” said Brooke Berrios, who oversees the program for Fresno County Office of Education. “And it currently does not.”

Berrios said early-career teachers typically work at these districts for a few years before leaving for a suburban district. It costs about $9,000 each time a district has to hire a new candidate — a significant bite for small rural districts.

“Historically these schools have been so underserved that they’ll take anybody,” Berrios said. “The cost of hiring isn’t always equitable.”

Sometimes, the problem can be as simple as filling out the paperwork.

Applications for state grants can be dozens of pages long and require several staff members to complete. If the district gets a grant, then staff must also oversee how the money is spent. It’s an issue that plagues rural districts such as Lassen Union High School District.

Nugent, the superintendent of Lassen Union High, and his staff are already stretched thin, he said. Nugent himself regularly transports kids to and from school in a van.

“They benefit larger districts that have the manpower to apply for these grants,” he said. “There’s only so many hours in the day.”

The 800-student district, situated about 190 miles northeast of Sacramento, doesn’t have any four-year universities in its vicinity. Chico State is about 2 hours and over a hundred miles away.

“Chico graduates get hired in that community before we even have a chance to reach out to them,” Nugent said. “We don’t have access to highly qualified individuals.”

The district currently has openings for two teachers and three teaching aides, and Nugent said he’s not confident he’ll be able to fill them. On top of that, he says, Lassen Union High is one of the few districts in the state where student enrollment is growing. The district also kept schools open for most of the pandemic.

Even so, Nugent said he feels like he’s getting little help from the state.

Snider, the lobbyist, said trying to address the staff shortage through one-time or even multi-year grant programs is unsustainable for districts.

He said district administrators are cautious not to sound ungrateful for the grant money, but the state needs to increase continuous, overall funding for schools so districts can give teachers more competitive salaries and attract talented candidates.

“You need to send ongoing money to schools,” Snider said. “Labor organizations and management share that perspective.”

The 2021-22 state budget contained a historic amount for teacher training, recruitment and retention. One of the largest investments was an ongoing increase in funding to the state’s highest-need school districts, totalling $1.1 billion. Districts receiving this money, must show how they’re using the money to hire more staff.

Anothing promising program, Kini of the Learning Policy Institute said, is the Golden State Teacher program, which would give college students up to $20,000 for committing to working at schools with the worst teacher shortages.

While districts will likely continue feeling the pain as they wait for these grant programs to bear fruit, Kini said she’s optimistic about the long term. The data, she said, shows a correlation between the state grants and an uptick in teacher preparation.

“We’re moving in the right direction,” she said.