Halfway through the first school year using an overhauled literacy program, Richmond’s Nystrom Elementary is beginning to see some early signs of success.

The 500-student Bay Area school obtained a waiver from West Contra Costa Unified that allowed it to discard the district’s previous reading curriculum, which has been criticized for not focusing enough on phonics. It replaced the program with one that has a greater emphasis on phonics, paired with research-based classroom practice in an attempt to bring every student to grade-level reading. Thus far, the school has seen “growth across the board” on students’ reading skills, said principal Jamie Allardice. And an increasing number of students are expected to end the year on track, he added.

The districtwide curriculum, Units of Study for Teaching Reading English/Language Arts, remains in use throughout the country and still has its supporters. But the school felt that in order to improve on years of lagging reading scores, the best method would be to switch to the increasingly popular “science of reading” approach to literacy instruction. An assessment at the beginning of the year showed the majority of students at Nystrom were behind grade level on their reading skills, so much so that they likely wouldn’t get up to speed without additional help.

GOING DEEPER

Common terms in the teaching of reading:

Phonics is the identification of the sounds letters make in a word and is the basis of learning to read.

Decoding means translating a printed word to speech and identifying unfamiliar words by sounding them out.

Three-cueing is an often-criticized method of using context, pictures, syntax and parts of words to guess the meaning of words that a student is stumbling on.

Balanced literacy, or whole language, refers to the approach to literacy instruction centered on a student learning to read naturally by exploring their literature. The approach includes the explicit instruction of phonics, but only for a limited amount of time.

Science of reading, on the other hand, refers to a literacy instruction approach based on developing research that learning to read is not a natural process and requires a heavy emphasis on phonics in order to teach students to connect letters and sound out words.

Allardice and Margaret Goldberg, the school’s literacy coach, chalk up much of the improvement to offering new types of reading intervention to all students under a “science of reading” approach, baking it into the core instruction at the school and training teachers to be reading experts themselves.

“If we believe all of our kids can read, we need to do some things differently and adjust for their needs,” Allardice said.

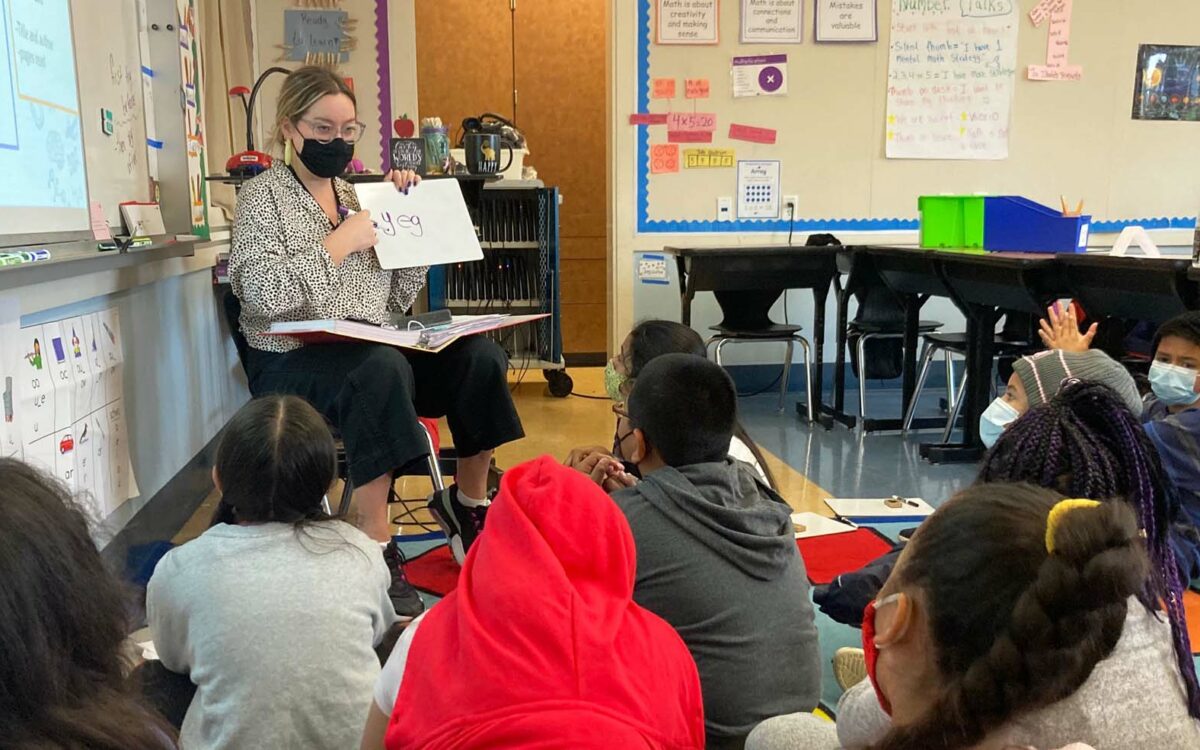

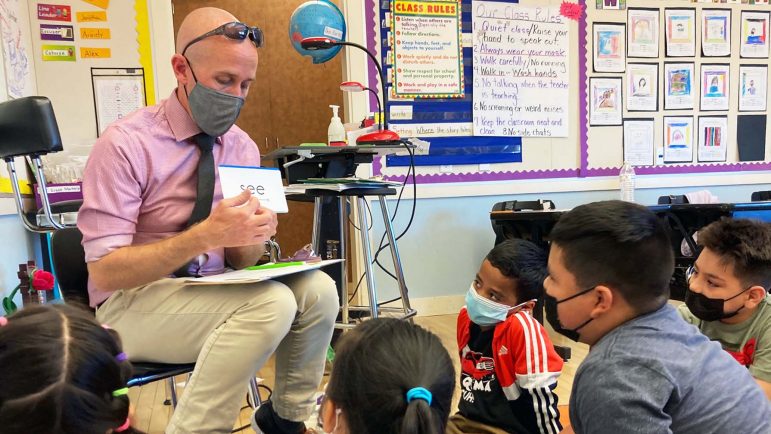

Part of the day for Nystrom students entails a group reading lesson tailored to their needs, as well as guided practice. Students are also consistently assessed to see in which areas of literacy they need help.

The reading wars

The school’s previous curriculum, Units of Study for Teaching Reading English/Language Arts, also known as reader/writers’ workshop, has been criticized in recent years for not focusing enough on phonics; that is, the process of pronouncing words by identifying the sounds letters make. Experts say students who struggle to grasp phonics often get left behind.

Though the curriculum includes daily phonics lessons, critics say it pressures teachers to limit those lessons to around 10 minutes and no longer than 20 minutes to allow for more time for reading and writing “workshops” – where students are given uninterrupted time to read and write on their own. A typical Units of Study “mini-lesson” consists of a teacher demonstrating a reading or writing skill or explaining a concept such as the use of characters in their books, and engaging with students by either showing them how to do the skill on their own or having the class discuss a concept.

Students get time to practice their literacy skill — usually around 10 minutes with the whole class — but experts say there is not enough practice time to ensure all students learn to read.

The curriculum has also been under fire for the practice of “three-cueing,” or using context, pictures, syntax and parts of words to guess the meaning of words that they are stumbling over. Researchers say it is not a valid alternative to decoding, or figuring out the meaning of words.

Still, it remains the dominant elementary English/language arts curriculum at West Contra Costa Unified.

Goldberg is among a growing number of critics of the“balanced literacy” or “whole language” approach that Units of Study takes, which is based on the belief that children will, for the most part, learn to read naturally by pursuing a love of literature. The “science of reading” approach, on the other hand, points to research showing that learning to read is not a natural process like learning to talk. Instead, it comes from explicitly teaching children how to connect letters and words.

Arun Ramanathan, CEO of Pivot Learning, a nonprofit education consulting organization, said a growing number of schools throughout the country are turning away from the Units of Study curriculum as research develops showing its shortcomings. In a 2020 report by Student Achievement Partners, K-12 literacy experts said the program mainly benefits children who arrive at school “already reading or primed to read.” But students who need additional practice in specific areas of reading or language development – especially English learners – are likely to struggle with it.

“Fundamentally it doesn’t work to teach kids how to read, particularly kids in districts like Oakland and West Contra Costa with high concentrations of poverty and kids coming in without a lot of the foundational skills that they might come in with at wealthier and whiter districts,” Ramanathan said.

Lucy Calkins, the founder of Columbia University’s Teachers College Reading and Writing Project and the creator of Units of Study, has pushed back against the criticism against the curriculum. She agrees that explicit phonics instruction is crucial for early readers, but argues too heavy of a focus on phonics could prevent students from becoming avid readers. She remains skeptical of some research supporting the “science of reading” approach, saying there is evidence on both sides and asserting that no one gets to own the term “science of reading.”

Nystrom now uses a new curriculum, EL Education, and the Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words program, or SIPPS, in order to take a “science of reading” approach. Science of reading refers to a growing body of research on how children learn to read that calls for a phonics-heavy program. The decades-old disagreement between the two camps has been referred to as the “reading wars.”

The “science of reading” approach centers on the idea that learning to read is not a natural process like learning to talk. Instead, it comes from explicitly teaching children how to connect letters and words. The ability to decode words through phonics, as well as to derive meaning from them through language comprehension, is what makes a skilled reader.

Much of the difference boils down to the amount of time students spend on phonics instruction and applying those skills to reading. With a “science of reading approach, Nystrom students are getting 30 minutes a day of foundational skills instruction, 30 minutes of practice time and an additional hour focused on comprehension of grade-level texts, Goldberg said.

“It’s quite a lot more teaching that’s happening than a balanced literacy classroom, and as a result, there’s a lot more learning,” Goldberg said.

West Contra Costa Unified Chief Academic Officer LaResha Martin said she’s a fan of EL Education, which her previous employer, Oakland Unified, adopted last year after piloting it for two years in 19 elementary schools.

Goldberg also used to work for Oakland Unified as a literacy coach, and she advocated for EL Education’s adoption.

Despite the Units of Study curriculum receiving a scathing review in October from nonprofit curriculum reviewer EdReports, the rest of West Contra Costa is stuck with it for the time being.

That’s because the district only adopted it three years ago and it only has the money to adopt one new textbook each year, said Martin, who started at the district this year. The district is already in the process of adopting new textbooks for middle school science this year and history/social studies next year.

Martin said a textbook change can cost upward of $1 million, and the district’s budget for textbook changes is $1.7 million. Changing course would mean a textbook for a different subject or grade level won’t be updated.

Nystrom and some other West Contra Costa schools were only able to replace it with EL Education after receiving a waiver from the district, as well as the funding to pay for its own textbooks, workbooks and instructional materials.

Early literacy will be one of the district’s major focuses next year, Martin said. The district formed an early literacy advisory committee that will be bringing Martin proposals regarding curriculum and program expansion in the coming months.

Martin will then make a proposal to the school board for next year and plans to bring SIPPS to all schools in the district next year.

A boost in funding

Nystrom was among a handful of West Contra Costa Unified schools to receive extra funding to boost its reading instruction through the state’s Early Literacy Support Block Grant, which was the result of the 2020 settlement of a lawsuit filed on behalf of California students who struggled with reading. California has long been challenged by its low reading scores, as well as with disparities between low-income and Black and Latino students and their white and wealthier classmates.

The settlement rewarded 75 elementary schools across the state a total of $50 million in state block grants for literacy coaches, teachers aides, training for teachers and reading material that reflect the cultural makeup of the student population. The schools chosen for the grants were those that had the highest percentage of third graders scoring at the lowest achievement standard level on the State Summative English Language Arts (ELA) assessment.

At Nystrom, teachers conducted DIBELS assessments at the start of the year in August and again in late October to measure students’ reading skills. DIBELS stands for Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills and consists of highly specific, grade-level assessments that can be used to predict whether students’ reading skills will grow on track throughout the year or if they need additional help.

“If most of your kids need intervention, you need to set up a different kind of literacy plan,” Goldberg said.

The first assessment showed that 61% of all students at the school were “behind benchmark” – meaning they didn’t have their grade-specific reading skills. Those students had an 85% chance or more of remaining behind benchmark at the end of the year without some type of additional intervention, Goldberg said.

By the middle of the year, however, there was significant improvement among first and fourth graders, Goldberg said. The school expects to see more growth as assessments are analyzed.

At the start of the year, only 7 of about 60 first graders were reading at grade level, Goldberg said. The October assessment showed that phoneme segmentation fluency, the ability to hear the sounds in words, had jumped from around 20% to around 40% among first graders. First graders also saw significant growth in nonsense word reading fluency — the ability to sound out unfamiliar words — and word reading fluency – the ability to recognize frequently used words.

Across all grades, “oral reading fluency has shot up,” Goldberg said, meaning students are able to understand the texts better and read them out loud.

“They’re much more accurate and fluent in their reading, and that allows them to have the brain-space to comprehend what they’re reading,” Goldberg said. “We’re noticing that the achievement gap is starting to close in that group of students, which is really exciting.”

By the middle of the year, there was a 15% decline in rate of first graders needing “intensive intervention,” or support beyond the core instruction or supplemental instruction, such as small group or individual help. About 18% fewer kindergartners and 12% fewer second graders needed intensive intervention by the middle of year, Goldberg said.

The school employs a “walk to read model” for specialized reading instruction. When it’s time for reading intervention, students walk from their main class to a reading group composed of students of different grades grouped together based on what level of intervention they need. Goldberg said group reading intervention is more efficient than one-on-one or small-group tutoring, which is the way many schools approach reading intervention. Having worked at other districts, Goldberg said reading interventionists’ caseloads using small group tutoring typically only allow them to serve around 20 kids.

“There’s only so many sessions you can give to one, two, or three children at a time,” Goldberg said. “This (walk to read model) is a way to get every child who needs intervention the access to that instruction.”

Still, the school tries to keep groups smaller for students who struggle the most, Goldberg said.

What also sets Nystrom apart from other schools is the amount of instruction time devoted to what is called foundational reading skills. At most schools, Goldberg said, students get about a 20-minute whole-class lesson on phonics, followed by time for students to read independently, while the teacher circulates the room and maybe pulls together a small group of students who need additional help.

That style of teaching with a “light touch of intervention” is typical under the balanced literacy approach, Goldberg said. She predicts that style would have only allowed at most 10% of Nystrom’s students to progress normally.

One of the biggest signs of early success at Nystrom has been a sense of “excitement in the air,” Goldberg said, as students are having an easier time learning to read, and teachers are seeing their growth firsthand.

“We really tried to make it clear to (teachers) that they had literally changed the trajectory of those children’s lives, that they were on track to be behind in school, not only in elementary school because the kids who fall behind tend to stay behind,” she said. “These teachers had actually shifted their trajectory of achievement by getting them caught up and no longer in need of such support.”