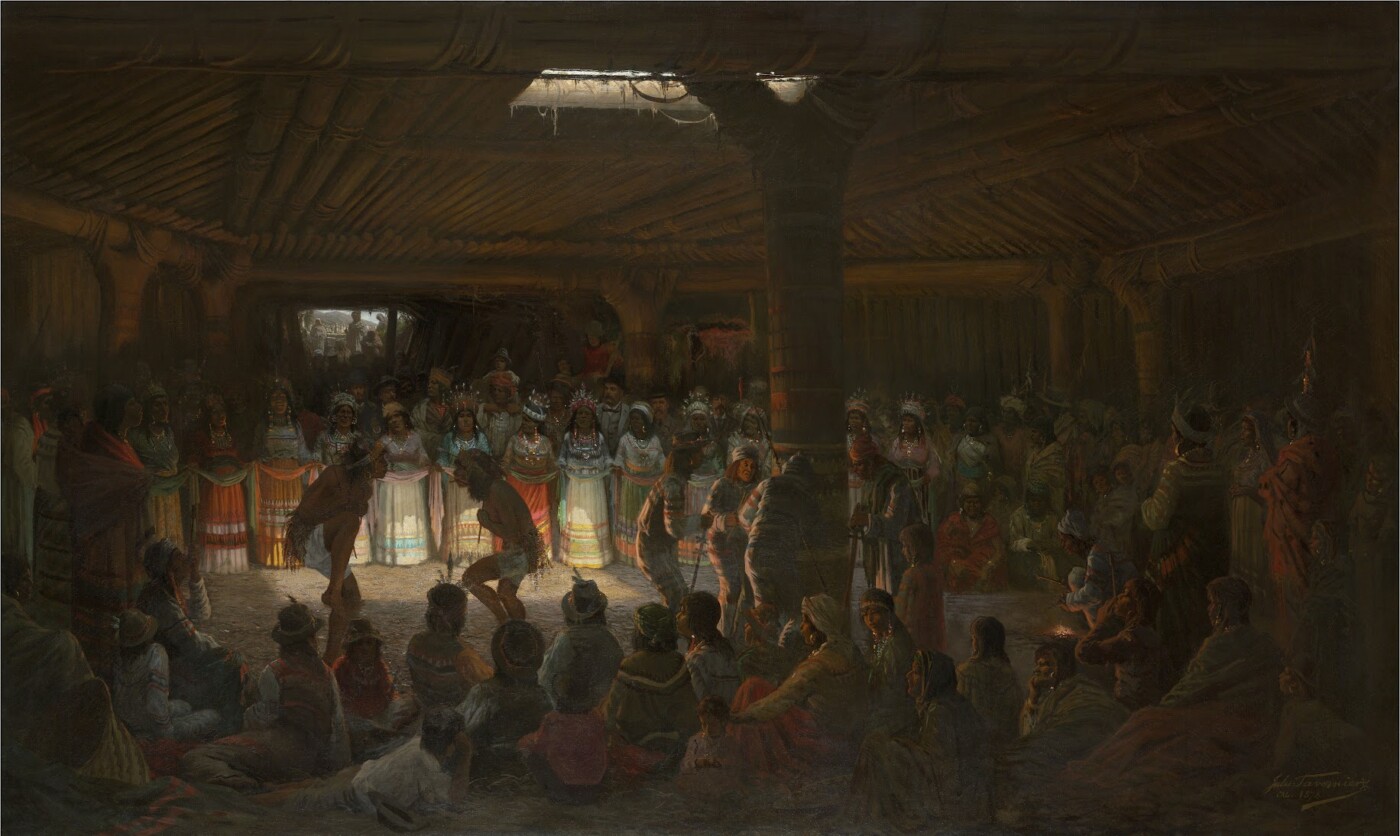

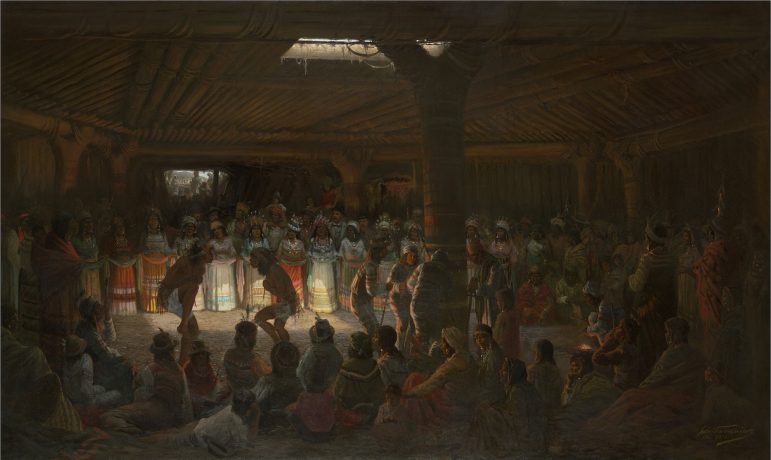

The centerpiece of “Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo” at the de Young is, as advertised, Tavernier’s recently rediscovered “masterwork” “Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California” (1878). Commissioned by Tiburcio Parrott, a wealthy San Francisco banking scion, the painting depicts a “mfom Xe,” or “people dance,” in an underground roundhouse (“xe-xwan”). It’s surprisingly tender in composition: no palpable hint of an anthropological gaze. The artist doesn’t leer at his subjects or exoticize them. He simply observes and translates what he sees to paint.

I’m generally averse to the idea of the “masterwork.” Categorizing any single piece as a “magnum opus” runs the inevitable risk of placing undue importance on singularity, rather than on an oeuvre. Growth interests me more than the lucky strike of genius. “Why focus on this piece,” I always wonder, “and not the aesthetic progression of the artist?”

Everyone knows Georgia O’Keeffe’s flowers, for instance. They’re universal. But aren’t her skull paintings — e.g. “Ram’s Head” (1935) — more pleasing and artful for their stark rendition of the demands posed by desert life and the brutal consequences of a single slip-up in such an arid climate?

I’m not alone in my apprehension. The late critic John Berger stated that the focus on “masterful” oil paintings pulls attention away from “what the tradition (of oil painting) was really about,” by which he meant enumerating property relations, flaunting capital and showcasing class status.

My misgivings aside, “Dance” is masterly: the iridescent glint of abalone jewelry stands out in the dark xe-xwan. Tavernier employs the impasto technique on one participant’s headdress to emphasize the ochre luster of its magnesite and to lift the headdress off the canvas. Thin shafts of light beam into the sparsely lit room. You could almost smell the earthy dank in the xe-xwan, feel the air clinging to the performers’ bodies. A single Y-shaped tentpole supports the structure.

For all its acumen and artistic prowess, contradictions tangle Tavernier’s “Dance.”

On the one hand, the painting celebrates the intergenerational power of the Pomo as they pray for protection against decimation. On the other, though, the ceremony is performed in the presence of a small cadre of white men, including a banker (Tiburcio Parrott), his business partner (Edmond de Rothschild) and their peers, emissaries of the culture carrying out the decimation.

If this were not painful enough, allow me to turn the screw a little tighter. In what is perhaps the most ironic twist, Parrott, the magnate who commissioned “Dance,” owned the open-pit Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine that was poisoning the very people he paid Tavernier to depict. Elemental mercury and sulphur leeched into Clear Lake, sedimenting into its lakebed and invading the flesh of its fish population for almost a century before the operation was abandoned in 1957. Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency 33 years later.

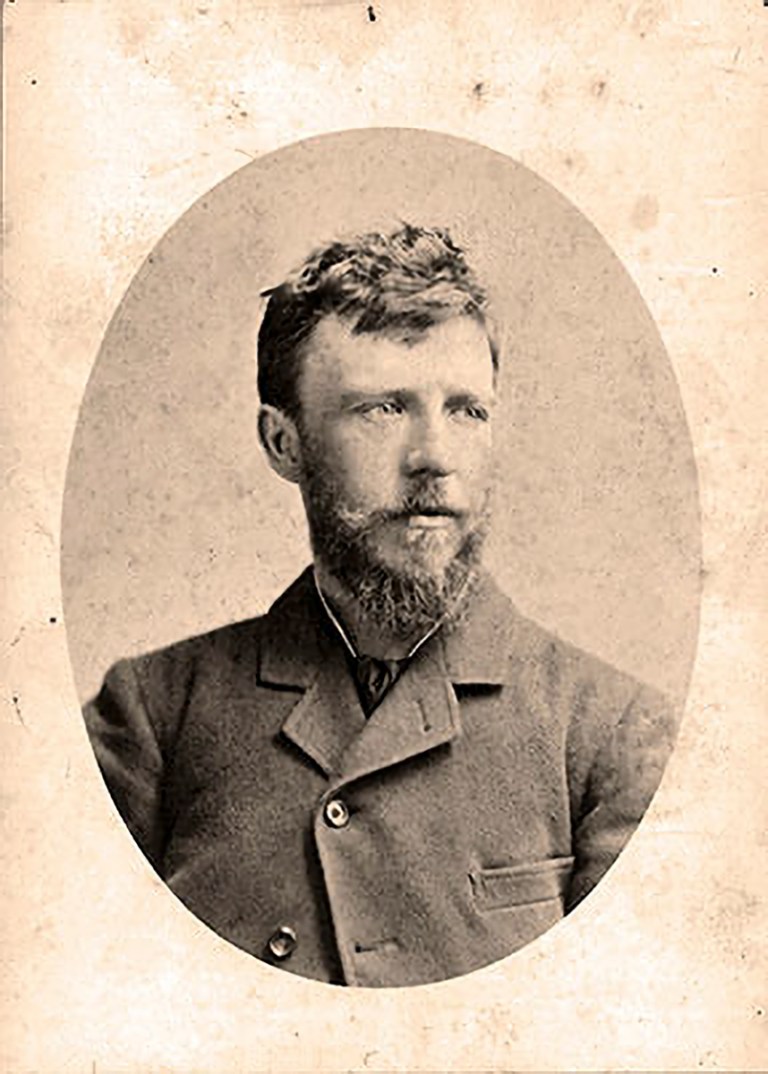

Frantic and a bit distracted by nature, Jules Tavernier was prone to missing deadlines and letting his debts pile up high. As a consequence, he lived a wayfaring life, drifting from city to city pursued by creditors who demanded he balance his books. He spoke at a blistering pace in an incomprehensible amalgam of French and English — “300 words a minute,” according to the poor reporter tasked with transcribing him in the 1880s. In another life he may have been diagnosed with attention-deficit disorder and prescribed Adderall or Clonidine to better hone his focus, but psychiatric medicine was still in its infancy in the 19th century.

Enough armchair psychiatry. I’m no shrink, and neither was Tavernier. The French painter received his formal education at the acclaimed École des Beaux-Arts, where he drew influence from the Barbizon school of painting, which emphasized natural light, earthen tones and picturesque landscapes. He took his Parisian training to the coasts of central California, where he formed a hotbed artists’ commune (the Monterey Peninsula Art Colony), and later to Hawaii, where he founded the Volcano School with a cadre of non-Native painters, including D. Howard Hitchcock, Louis Pohl and Ogura Yonesuke Itoh.

In California, Tavernier’s bold use of pastels garnered him critical acclaim and brought a much-needed flow of cash that allowed him to be more selective in his commissions. A master of medium, he tested the limits of form, even orienting his sylvan paintings of Yosemite redwoods and rock formations as portraits to further emphasize their height.

I first came across Jules Tavernier’s depictions of Native daily life researching an essay on tourism in the Caribbean and Polynesia. In the books I was reading — everything from academic monographs to travel journalism — Tavernier’s painted Hawaii kept appearing as either a visual nod to the origins of Hawaii’s fertile soil or as a metaphor for the islands’ volcanic latency.

Eruptions run wild in Tavernier’s work around this time, and the Kīlauea Caldera seemed to have particularly enthralled him. He painted it at least three times, each time capturing a different facet of it: the flaring heat, the venting, the clinkers. In Hawaiian cosmology, Kīlauea houses the goddess Pele, creator of the Hawaiian archipelago and wellspring for creation. To Hawaiian eyes, then, red-hot lava represents not molten violence, but the bubbling, erupting potential of life. (Some hula dancers in Hawaii climb Kīlauea to pay tribute to Pele before performing at prestigious festivals.)

This, I think, is what Tavernier does best: embedding lucid metaphor in natural landscapes. “What kind of pressure,” he asks his audience, “is building in these images? What’s seething below?” This was the 1880s, and Native Hawaii was in dire straits. White (“haole”) insurrectionists, along with their allies in the U.S. government, had begun to consolidate power. They plotted to topple the Hawaiian monarchy and impose an all-white government in the archipelago. Indeed, Native Hawaiians felt the considerable crush of outside forces: American encroachment, crumbling sovereignty and military occupation. Intermittent conflict erupted across the archipelago. Something had to give.

Unfortunately for Hawaiians, it would be their monarchy that would fall to a domino succession of coup d’état, defenestration and annexation. When a Native counter-coup attempt in 1895 failed to restore Lili‘uokalani to the throne, Hawaii’s queen was placed under house arrest at her ‘Iolani Palace, where she formally ceded her claim to power. Hawaiian sovereignty splintered and its people languished in political limbo for another 64 years. Hawaii featured on the United Nation’s list of Non-Self-Governing Territories from the organization’s founding until 1959, when the archipelago was granted U.S. statehood.

Tavernier did not paint any of this, however; he died four years before the haoles executed the overthrow. Instead, after washing up on Hawaiian shores, Tavernier focused his energies on Hawaii’s lush, volcanic scenery. Nothing sexual or lecherous like in Paul Gauguin’s Tahiti. Only roiling potentiality and untapped power.

Curiously, Tavernier’s depictions of Hawaii don’t boast much basis in reality. The mechanics of geothermal energy, for instance, offer incriminating evidence that his “The Volcano at Night” (circa 1885-1889) was little more than skillful artifice. In it, Tavernier captures a Kīlauea coughing up molten lava (“‘a‘ā”) in acid oranges and molten reds. Nearby, the ground supercools into craggy, blue-black basalt. It’s nighttime, and lava glows electric against the surrounding darkness.

The smoking gun? His perspective. Tavernier painted this Kīlauea landscape from what appears to be a hundred feet or thereabouts away from exposed magma. Never mind the asphyxiating ash plumes or tephra of an active volcano, the lava itself could likely have reached over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, hotter than the melting point of gold. The resulting radiant heat might have burnt his face off. Regardless of its status as likely fabulation, the painting offers a beautiful snapshot of a visitor’s imagination erupting with metaphor and possibility.

Talk of artifice in Tavernier’s “Dance” gets at a problem I struggled with in pinning down the painting’s central messages. Artistic license is one thing — the baskets, for instance, a plaque reads, were added after the fact for cool factor — but assessing intention is something else entirely. Was “Dance” an honest rendering of reality? Or did this lean on imagination to sell an agenda?

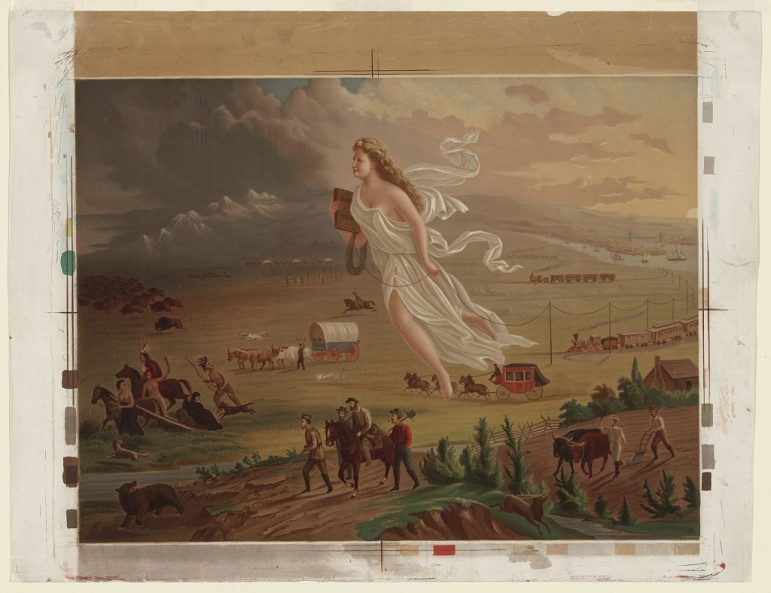

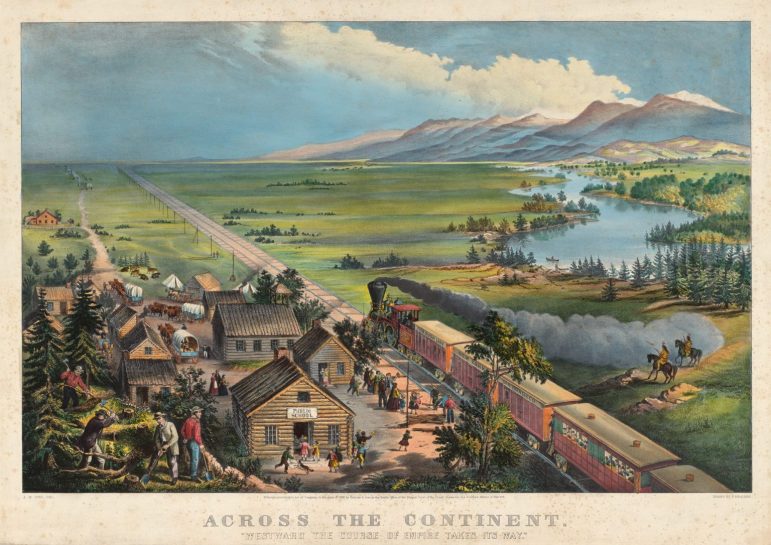

Why paint this scene and not another, similar, equally impactful one? Sometimes the mood strikes, swaying the artist one way over another. Often, nothing discernible explains a given brushstroke or slash of color. Sometimes, however, bias colors artistic choices. I’m thinking of the 1973 documentary “Painters Painting.” At its outset, the film’s director, Emile de Antonio, diagnoses “the problem of American painting” as “a problem of subject matter.” Not the subject (or subjects) in the painting so much as the subject of it. American painting, he continues, “kept getting entangled in the contradictions of America itself. […] We tried to find garden landscapes that we were destroying as fast as we could paint them. We painted Indians as fast as we could kill them. And during the greatest technological jump in history, we painted ourselves as a bunch of fiddling rustics.”

This painterly mythmaking turned out to be quite important to the colonial project because landscape paintings, the ones we usually associate with halcyon America, did a lot of ideological work that would otherwise have proven difficult to execute on a continental scale. For one, serene landscapes and other printed media perpetuated the myth of an uninhabited West. “Nobody’s here,” the canvases signaled to hungry settlers and desperate homesteaders, “so come build a new life for yourself.” Depiction and reality were one and the same: a painting of empty plains meant the Western Great Plains were empty. As reproductions of these works circulated in newspapers and books, they soon took on a life of their own in creating almost-incontrovertible facts on the ground: The West was open for white settlement.

For another, paintings bypassed a major obstacle to spreading this message: the written word. Illiteracy among whites in the 1870s hovered at about 20%. (For newly emancipated Black Americans, this number soared to 80%.) So, narrating the West as an empty wilderness in a visual language that poor, illiterate whites could easily understand became a crucial motor for ongoing Westward expansion. Paintings like John Gast’s “American Progress” (1872) or Frances Flora Bond Palmer’s “Across the Continent” (1868) achieved what books, newspaper columns and government pamphlets could not: near-universal understanding that, again, the West was open for white settlement.

Tavernier resisted playing into this phenomenon throughout most of his career, instead choosing to depict Native Americans with a caring, gentle hand. He positions himself in “Dance” as an interested observer to the mfom Xe ceremony, fascinated by the accompanying regalia and pomp. His hatchet-sharp observations rival those of any journalist or photographer. A line of women hold cloth around two young men performing a coming-of-age dance. A quartet of elders circle the tentpole that supports the Xe-xwan structure as a huddled crowd looks on. And finally there’s the subtle intimation of a darkness encroaching on the Pomo, a darkness that threatened to devour them whole.

The mfom Xe ceremony arrived in the Pomo Nation at a moment of great strife and social upheaval. Many were still reeling from the aftermath of the Gold Rush, which brought an influx of greedy forty-niners and, with it, violent encounters with white mercenaries tasked with dispossessing Native Americans from profitable land. Population collapse escalated, along with despoliation of the natural landscape.

Remember that miners during the Gold Rush “moved mountains” with hydraulic mining to extract gold from the Californian soil and satiate their gold fever. In tandem with this fever arose a terrible bloodlust that cost the lives of about 120,000 Native Americans, largely women and children, from 1846 to 1870. The historian Benjamin Madley appraises the period as “the organized destruction of California’s Indian peoples.” The first governors of California, all military colonels, tacitly permitted the genocide.

A Pomo prophet emerged from this violent tableau with answers to the threats posed by outsiders — as prophets tend to provide. (Think of Jesus of Nazareth, who rose to prominence as a messiah during the turbulent 1st century, advocating nonviolent resistance, harmony and a peace-and-love mantra reminiscent of Flower Power hippies.) In this moment, ripe for prophetic quick fixes, it’s easy to imagine just the how seductive the mfom Xe’s promises of imminent justice were to the Pomo. They must have been fearful for their survival, their culture’s endurance. I imagine that, for the Pomo, the mfom Xe pried open a window of optimism to a people decimated by outside interference. Survival by any means necessary, no matter what the White Man did to them.

Indeed, Natives across the continent were finding solace in similar movements that responded to the cultural and social devastation brought on by colonization. No case better exemplifies this trend than does the Ghost Dance, which, as it happens, was contemporaneous with the mfom Xe. Developed by the Paiute medicine man and prophet Wovoka, the messianic Ghost Dance cult quickly grew into a continental movement in the 1890s — a little over a decade after Tavernier painted “Dance.” Wovoka prophesied his ceremony would punish white settlers with banishment, repair a deteriorating social order and ultimately restore lands to Native control. Native Americans traveled far and wide to hear him preach his gospel of Indian empowerment and uplift.

White outsiders observed the movement with suspicion and outright fear. (Performers of the Ghost Dance often slipped into a trance after dancing for hours.) Fears over growing Native American unity and cultural activism would eventually turn violent. Nearly 300 Lakota Sioux were executed at Wounded Knee for their participation in the nonviolent ceremony, as part of what came to be called the “Ghost Dance War.” For their actions, 20 American soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor, the United States’ highest and most prestigious military decoration.

Neither the mfom Xe nor the Ghost Dance could ever hope to halt Westward expansion. Treaties went by the wayside as a fledgling American government permitted land-hungry settlers to seize increasing tracts of land. Conquest continued unabated until the frontier closed officially in 1890, marking the final colonization of what is now the United States of America. Unceded Native lands have yet to be returned.

In the meantime, Tavernier’s “Dance” persists as an artifact of its era, unchanged by the centuries of land grabs, violence and intergenerational trauma that ravaged California Indian communities. History has touched but not tarnished it; its core is preserved intact. Likewise, the basketry, regalia and jewelry on display persist as physical mementos of Pomo survival. Ingrained in these art objects are testaments to Native American endurance and genealogies of resistance that heartened but also challenged me as a (non-Native) viewer. For when objects outlive their creators, it’s up to us, the viewers, to do the work of remembering and repairing our collective past.

In early February, I got on the phone with cultural leader and regalia-maker Robert Geary (Elem Pomo) about the question of legacy. Interspersed with enlightening commentary on the importance of Native access to land and resources, Geary spoke about “what has happened to Native communities historically,” noting the persistence of these art objects in the aftermath of conquest and their potential for spurring a cultural resurgence.

He cited the successes of the California Indian Basketweavers’ Association in inspiring “pride again about who they are” and their work in building connections with conservation groups to reestablish Native access to the landscape. (In addition to his curatorial work with this exhibition, Geary is also a Xaitsnoo-language teacher, roundhouse leader and founder and president of the nonprofit Clear Lake Pomo Cultural Preservation Foundation.)

When I asked what he hopes the exhibition will convey to visitors, he suggested that learning the history of California, political education in other words, was of paramount importance, so that reciprocal relations can be nurtured between Native and non-Native people. And the objects on display are key to this education.

For Geary, most histories of the Elem people don’t sit in museums or on the shelves of archives — not the accurate ones anyway — but instead lie “in the ground” with “our ancestors” and in “our artifacts … everything that was a part of our connection to this land.” The land itself is teacher, provider for the seven tribes that call the Clear Lake area home, each with distinct cultures, values and traditions. These baskets, this regalia are not merely objets d’art, Geary reminded me, but warehouses of indigenous knowledge in miniature, a wellspring of inspiration for Native people today.

Such “renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry” kindle “an active sense of presence,” as the scholar Gerald Vizenor had it. Also kindled is the desire to seek out other instances of “presence” where “absences” typically proliferate. (For instance, I caught myself thinking about the Native-led movements to help locate missing and murdered indigenous women and Native-led land management and stewardship nonprofits while perusing the exhibition.)

Long have scholars in the fields of ethnic studies and history argued that Native people’s claims to this continent stretch further back than is generally believed. And recent findings substantiate this claim. In an article published in the prestigious journal Science, a team of 13 archaeologists arrived at the conclusion that humans lived in North America as far back as 23,000 years ago — long before written history was recorded and, for that matter, millennia before the invention of the first writing system. In other words, from time immemorial.

It’s worth noting that the racist science and scientific beliefs of Tavernier’s day held that certain races were bound to disappear. In this thinking, the “inferior races” were already marching along a road to extinction. Genocides like that against California Indians were, therefore, understood as unfortunate, but necessary to help Native Americans meet their “fate.” They were never meant to survive.

But they did. In spite of the obstacles and policies thrown up in their way, the Pomo Nation survived as stewards of their ancestral lands able to chronicle the story for themselves.

“Jules Tavernier and the Elem Pomo” will show at the de Young Museum until April 17. The museum is open 9:30 a.m.-5:15 p.m. Tuesdays-Sundays, and general admission is $15. The first Tuesday of every month is free to visitors, and Saturdays are free to Bay Area residents of all nine counties. Bring a driver’s license or piece of postmarked mail for proof of residence. For more information, visit https://deyoung.famsf.org/.