For weeks, Gov. Gavin Newsom teased that California would soon enter a new phase of its response to the coronavirus pandemic, one in which the state shifted its perspective to how to deal with an endemic disease that will likely be a regular part of our lives.

But when that moment arrived Thursday, Newsom made clear that the new strategy did not mean the fight was over. His long-awaited announcement came with no eulogy to the pandemic, no lifting of additional health restrictions and, despite growing calls from conservative critics, no end to the state of emergency that began nearly two years ago.

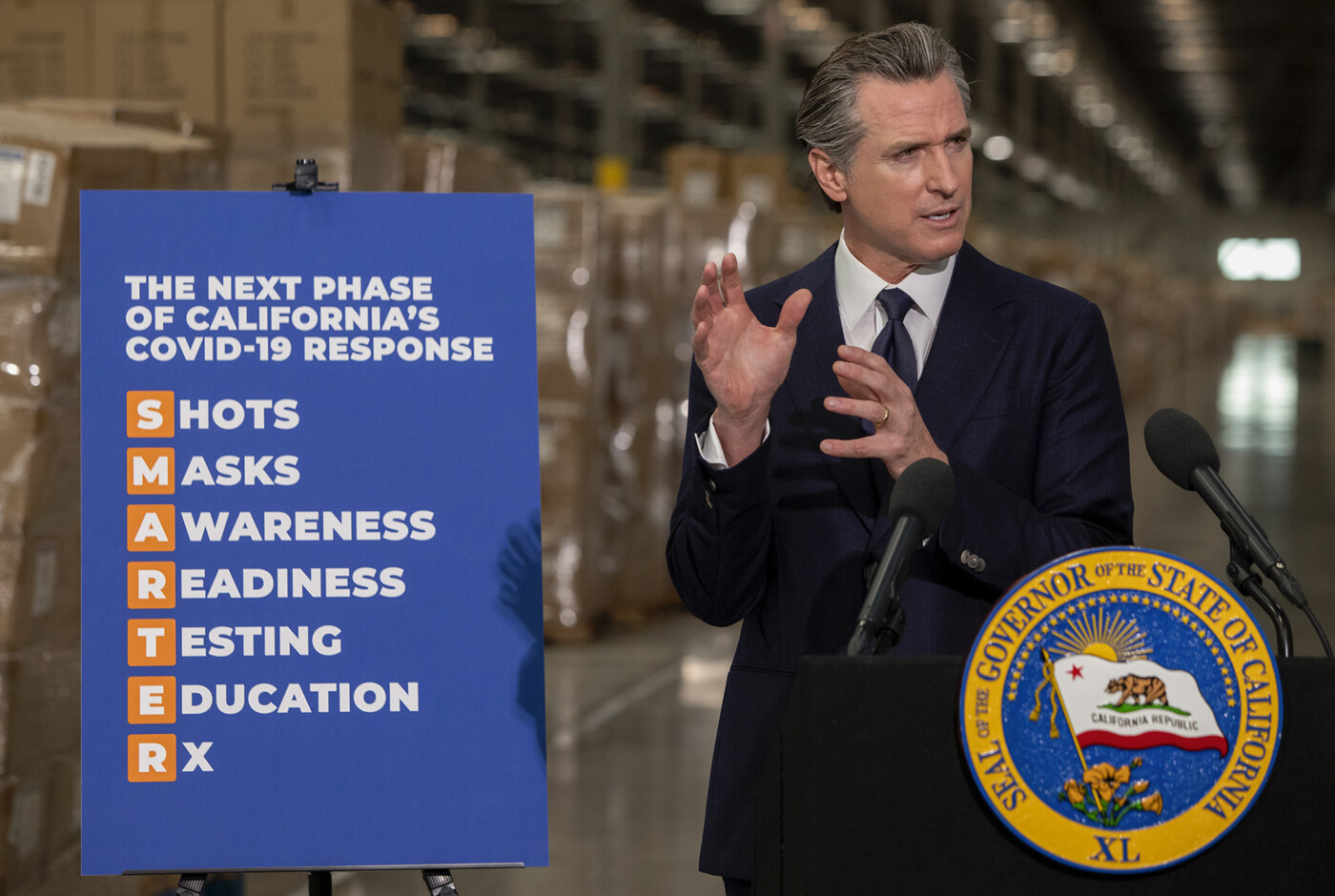

During a press conference at a San Bernardino County warehouse where his administration stores personal protective equipment, Newsom said early rhetoric envisioning a war against the virus was misguided. He could not offer a final destination for the battle, he said, only a direction in which the state would keep moving.

“We have all come to understand what was not understood at the beginning of this crisis — that there is not an end date, that there is not a moment where we declare victory,” Newsom said.

What Californians did get from the governor was an acronym, SMARTER, for the state’s priorities as it prepares for a future that may include more variants and surges.

It’s a reflection of the tricky political dance awaiting Newsom as people increasingly seem done with a virus that is not yet done with them.

A poll released this week by the Los Angeles Times and the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies found that, by a margin of two to one, California voters believe the coronavirus situation is improving.

Yet even as the rate of new cases has fallen precipitously from the peak of the omicron surge, down about 90% from a month ago, it is still at roughly the same level as the height of the delta wave last summer.

“We are moving past the crisis phase into a phase where we will work to live with this virus and we will maintain a readiness posture,” Newsom said.

While he overwhelmingly beat back a recall last year by leaning on his forceful response to the pandemic, enthusiasm appears to be waning for the governor’s approach. The L.A. Times poll found voters were nearly evenly split on his handling of the coronavirus, with 39% of respondents giving Newsom excellent or good marks and 40% giving him a poor or very poor rating.

That tension is concentrated in a fight over the state of emergency that Newsom declared on March 4, 2020, giving his administration broader authority to address the pandemic. He has issued dozens of executive orders under those powers, some of which remain in effect.

Earlier Thursday, before Newsom rolled out his plan, state Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins announced that a Senate committee would consider a resolution to end the state of emergency at a hearing on March 15.

Republican legislators gloated. They point to the ongoing emergency as a symbol of what they regard as Newsom’s overbearing and dictatorial approach to the pandemic.

In recent weeks, they have repeatedly and unsuccessfully tried to bring up the resolution, which has sat on the shelf for more than a year, for a vote on the Senate floor.

“It’s been 715 DAYS since Newsom began his one-man rule. He has completely side stepped the checks and balances put in place to bring accountability to government,” Senate Republican Leader Scott Wilk of Lancaster tweeted Thursday. “It’s time to bring an end to this madness.”

But their effort is unlikely to go far. In the same statement announcing the hearing, Atkins, a San Diego Democrat, defended Newsom’s emergency powers, noting that many states of emergency in California for wildfires and other natural disasters continue for years to assist with recovery and seeking federal aid.

A representative for Atkins said the hearing would give Democrats a platform to lay out what the state would lose by ending the emergency and what would not change — namely, a mask mandate for schools that Republicans have railed against, which was issued under a separate public health law.

“I understand we are all tired of living life in an emergency,” Atkins said, “but ending the emergency must be done responsibly to ensure there are no unintended consequences so we can continue to meet the need of our state’s residents in an unpredictable future.”

Dr. Mark Ghaly, Newsom’s secretary of health and human services, made a similar argument in a call with reporters. He said the state continues to rely on emergency orders to manage the coronavirus, including a waiver that let medical facilities staff up with temporary workers during the omicron surge.

The document laying out Newsom’s SMARTER plan pointed to other provisions that have allowed the administration to use state fairgrounds as testing sites and sidestep the normal procurement process to more quickly buy millions of home test kits for schools.

“As we move out of the mindset of an emergency, we need to make sure the tools that help us manage an emergency well are available,” Ghaly said. “These are the tools that have allowed us to protect Californians in quite an incredible way. We are still using them today.”

Newsom did not directly address the criticism over the state of emergency during his press conference. But in an interview with the New York Times, he said “his goal was to unwind the state of emergency as soon as possible.”