The two faces in the canvas float in darkness. Their proximity to each other — their bodies would likely be entwined if you could see them beneath the water or mist swirling around them — suggests a close and possibly familial relationship. Who are they? What are they doing? There may be no clear answers but there are worlds of possibilities in Oliver Lee Jackson’s enigmatic art.

For more than a half century, the Oakland-based artist and retired art professor has been steadily creating his arresting paintings, sculpture, mixed media, drawings and prints. Rooted in the human figure, Jackson’s art can feel like many things, often at the same time: His use of materials can seem playful but is always intentional; his works are taut, tender, challenging, emotional and mysterious.

While he may not be a household name, Jackson is no stranger to the art world. His work is in the collections of some of the most prestigious art museums in the country, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Last year alone, his work was the subject of four solo exhibitions, including at the Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri, Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco and the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art in Napa, where his show, “Oliver Lee Jackson: Any Eyes,” runs through Feb. 20.

Now 86, Jackson seems to be at the height of his artistic powers, masterfully blending materials and mediums. The newest works in the di Rosa exhibition are sculptures made during the nearly past two years of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which curator Diane Roby described as an incredibly productive time for the artist.

“[The pandemic] has allowed him to finally get some works done that he’s wanted to for years,” Roby says.

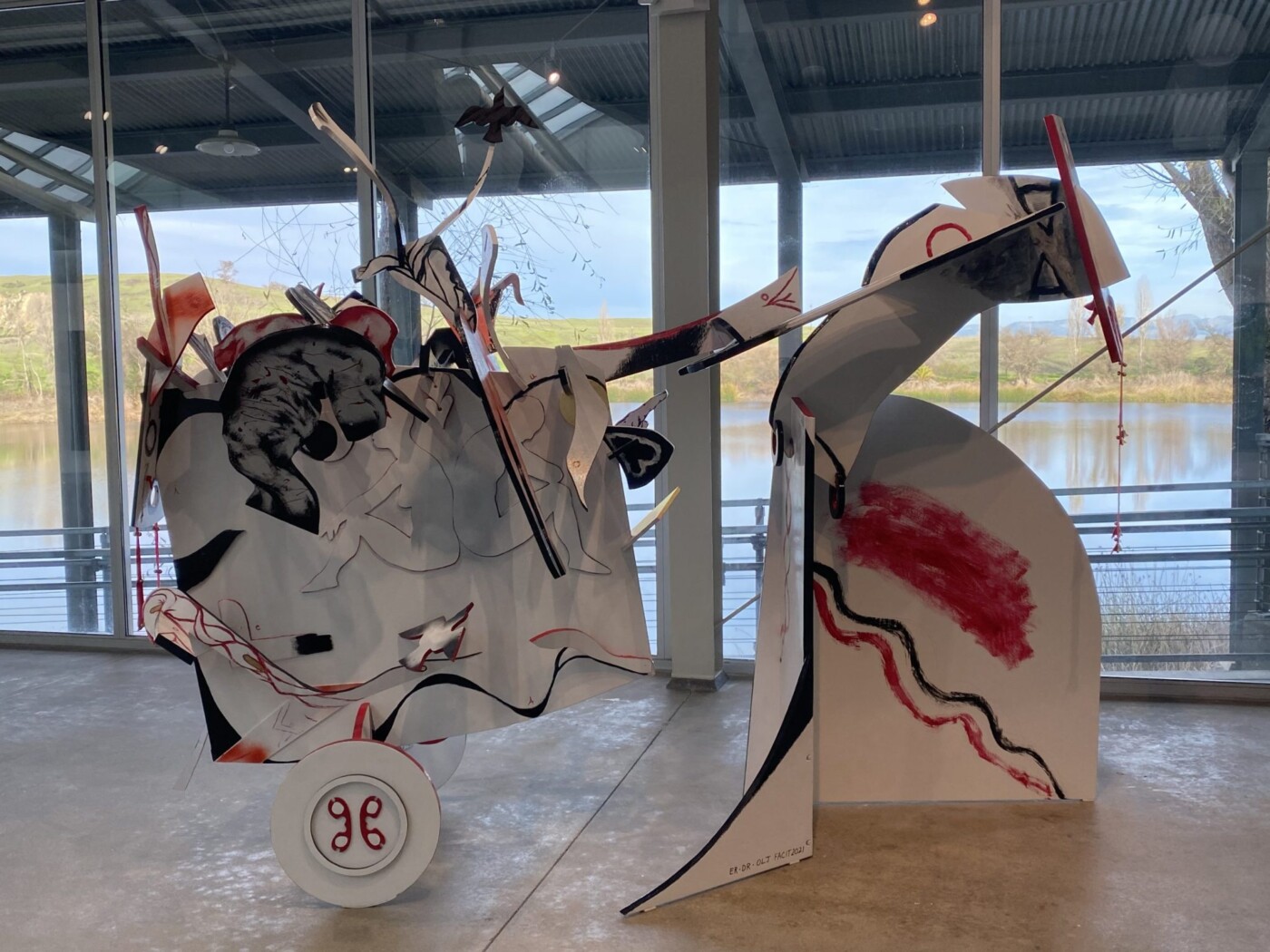

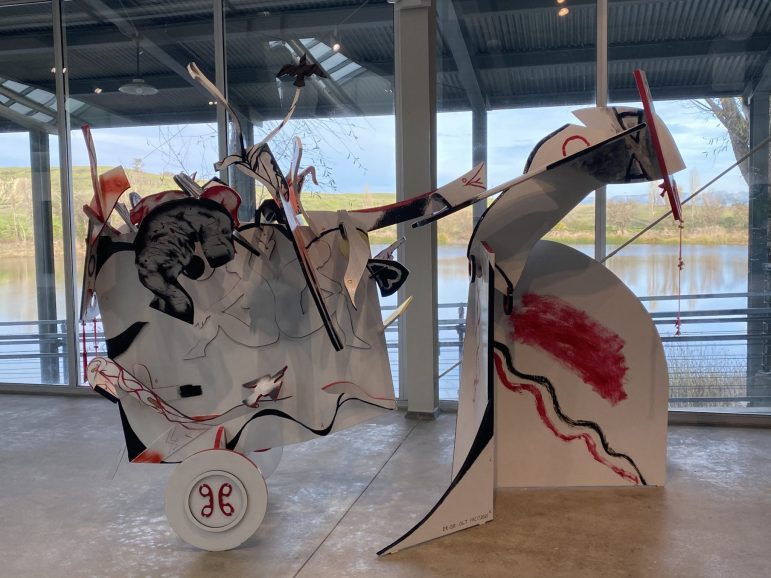

Those pieces include “Untitled (Figure with Cart)” a monumental sculpture Jackson fashioned from plywood, paint and other materials. The three-dimensional form asserts itself in space with powerfully expressive lines and angles. Its painted and decorated surface echoes the mark-making and textures on the paintings and tapestries elsewhere in the show. But the real feat is how Jackson is able to manipulate a humble material like plywood and turn it into a figurative object that seems imbued with the weight of the world.

Roby, who first started working with Jackson in the early ’80s and is now his studio manager, says the figure is an important image that’s been in the artist’s work for decades. Sometimes the figure is pulling a cart; sometimes it is carrying a big bundled load on its back. As the motif has evolved over time, the contents of the cart have become more and more defined: bodies, sometimes bloody parts of bodies, musical instruments, birds, babies, lovers.

“It’s this kind of full realm of the stuff of life,” Roby says.

Elsewhere, a pair of steel sculptures does a tenuous dance in the gallery, their metal bodies and painted surfaces pierced with holes that are festooned with fabric strips and bells.

Though the figures seem to be in some stage of distress, there’s an unmistakable playfulness in the way they’re made. It’s as if Jackson can’t help but revel in his materials, effortlessly deploying calligraphic squiggles and ghostly washes of paint.

A seasoned educator who began his career in his birthplace of St. Louis facilitating art education in the community on his own and as part of his association with the Black Artists Group, Jackson remains philosophical about his approach to making art and any expectation from viewers.

While observers might see his pieces and make their own interpretations or “value judgements” about them, Jackson encourages a different approach to experiencing his art.

Curator Roby quotes Jackson in the exhibition pamphlet: “The point is not to have ‘meaning’ — but does it have significance as it stands before you?” In other words, Roby explains, do the pieces grab your interest? How do they make you feel?

“Oliver Lee Jackson: Any Eyes” runs through Feb. 20 at di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art, 5200 Sonoma Highway, Napa. The center is open 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Fridays-Sundays; admission is free for children and $17-$20 for adults. Jackson will speak about his art in conversation with curator Diane Roby at 3 p.m. Feb. 12 at the center. For tickets and more information, visit dirosaart.org.