You have to walk through a millennium of Native American art before arriving at Nampeyo. She’s at home among the Maya stone sculptures, Pueblo pottery, Yokuts ceremonial basketry, and Yup’ik walrus tusk and whale bone carvings that make up the de Young Museum’s “Art of the Americas” wing. The rooms are cast in soft, dispersed light to protect the photosensitive pieces, reverential lighting that is usually reserved for cathedrals or icons. It feels both deliberate and apt. The gentle shafts of light impress upon visitors the sanctity of the pieces.

Nampeyo of Hano, a Hopi-Tewa artisan, is the grande dame of Hopi pottery, with a legacy almost unparalleled in Native circles. At “Nampeyo and the Sikyátki Revival,” the exhibition’s layout emphasizes the central role of her work in the history of Native American art. Her vessels sit on two pedestals in the center of the space surrounded by work she borrowed from and work by contemporary artists who borrow from her. There’s no cut-and-dry chronology to the pieces collected, no historical procession. In its place, co-curators Bobby Silas and Hillary Olcott host a quiet conversation between past and present, between ancestral Hopi potters and contemporary artists like Steve Lucas and Les Namingha, both of whom just happen to be Nampeyo’s great-great-grandsons.

The accumulated history of the pottery is actually quite astonishing. Some date as far back as the 14th century — 200 years before Juan Ponce de León, the first European to beach the continent, washed up on Florida’s shores, and more than 500 years before settlers built the first permanent structures in present-day Flagstaff, Arizona, only two hours outside of today’s Hopi Reservation. In the meantime, Hopi safeguarded 20-odd generations of tradition, some of which is now available for viewing at one of America’s premier art museums.

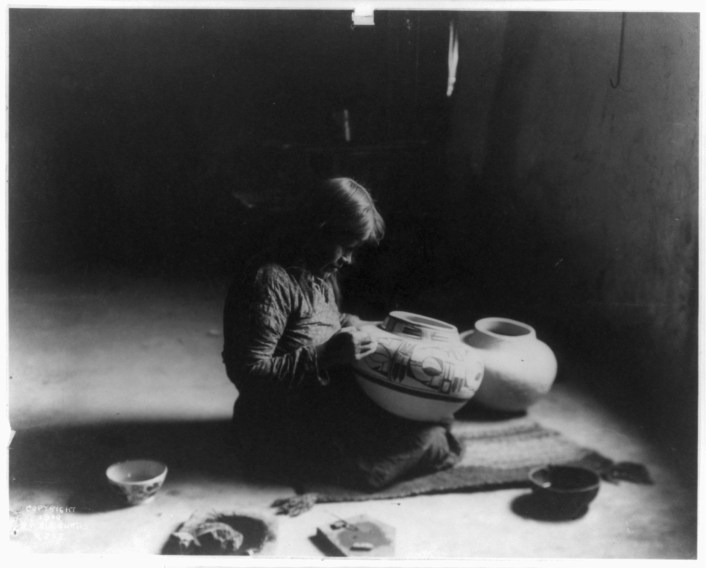

There’s a pared-down beauty to the vessels on display: the technique, the careful hand, the balanced compositions. As gorgeous as they are, though, these objects originally served a functional purpose — storage — and only incidentally acted as art objects (if such a distinction can be made). The chipped mouth of one shallow, beige bowl (circa 1900), worn down by years of affectionate use, reminds the viewer that this was once a household utensil, possibly an heirloom.

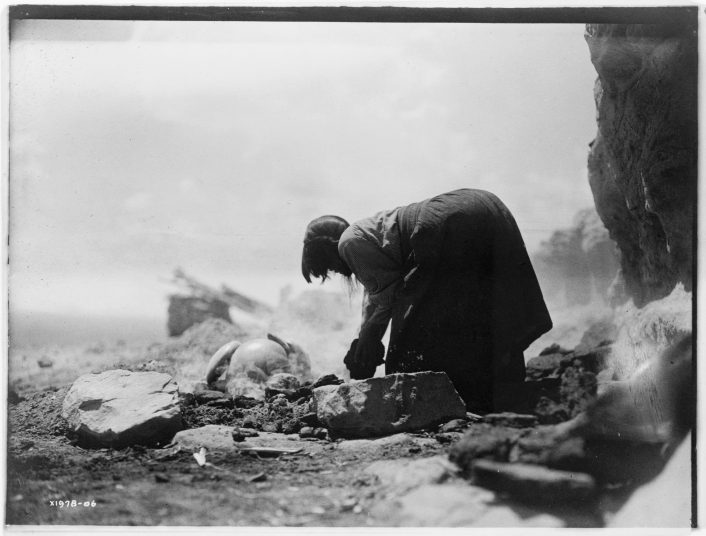

A brief note on her methods. Nampeyo didn’t have a wheel to throw her clay or an air-conditioned studio in which to work — much less a supply store from which she could purchase materials. No, each piece was borne of hard labor and inherited know-how. First, Mesa Hopi lacked running water, so Nampeyo carried the precious resource over miles of arid, searing terrain to hydrate the clay-rich soils she coiled into vessels by hand, massaging the sunbaked clay into a malleable consistency. A kiln was constructed out of stones and kindled with sheep manure, wood and black coal — a firing technique learned from Spanish ceramicists who settled in the region. In addition to reaching higher temperatures, the Spanish method — which sometimes called for sheep bones — offered the added benefit of further whitening the pottery, allowing painted colors to really pop. Nampeyo’s pigments derived from the earth: yellow ochre, red iron oxide and black hematite and boiled beeweed. Beginning to end, a finished product could take multiple days to produce.

But what can be said of the woman behind the work?

Sometimes very little. It’s difficult to pin down even basic biographical information (i.e. the precise year she was born) or verify much of what Nampeyo said. Some of what’s written about her has the uncanny air of invention because anthropologists and art collectors mediated her image to the world. From what is known, she cuts a humble figure, acquiescing to outsiders’ photographs but never leaving a signature on her earthenware. Each work is “Attributed to Nampeyo,” the captions read, by art historians and collectors familiar with her style. Credit for her virtuosity arrives late to the scene.

Meanwhile, most photographs of her were captured as archival material by ethnographers who staged her to look diminutive among her wares. The implication being that “the work drowned the artist” when, in reality, the opposite was true. She was a prolific artist with a careful control of her medium.

“Traditional” works like Nampeyo’s aren’t simply a gift from the past, they’re often a negotiation between recovered style and contemporary art practice. Nampeyo was born in Hano Pueblo in present-day Arizona around 1860. She was in her mid-30s when the anthropologist Jesse Walter Fewkes led a Smithsonian-funded excavation of Sikyátki, a former Hopi village on First Mesa, which had been abandoned by its inhabitants in the 17th century. The excavation began in earnest in 1895, and soon Fewkes unearthed numerous, well-preserved ceramics of Hopi origin.

Already a skilled artisan by then, Nampeyo learned to paint from these shards and, in borrowing from the recovered artifacts, developed what would come to be known as “Sikyátki Revival style.” She spent the next decades working within its strictures, building a number of unique aesthetic markers. Her signature “saucer” shape blended form and function: The curvature prevented rodents from climbing into the vessels and spoiling the food stored inside. (Such utility is what sets pottery apart from other art forms.) Perhaps the most famous of her motifs is the avian “migration pattern,” which narrates the diaspora of Hopi across the continent, over land and lake.

Though the meaning behind the imagery is admittedly “difficult to understand at first glance,” according to one caption, the illustrations can be understood as a “permanent prayer” for rain and bountiful harvests.

I recently spoke about Nampeyo with Gerald Clarke, a Cahuilla multimedia artist and professor of ethnic studies who teaches at the University of California, Riverside. Clarke explained that Nampeyo served as a bellwether for the future of Native American cultural production. By the turn of the 20th century, just before she lost her eyesight to trachoma, a preventable infection that hardens the cornea, her work in ceramics established the aesthetic standard for Native American pottery and ceramic wares, a standard that holds to this day. Her Sikyátki Revival style is “still the standard that non-Native collectors desire,” Clarke told me, and, consequently, what many Native American artists produce.

Native American art, he went on, “has evolved over the past century from being categorized as ethnographic artifact (sometime oddity)” to being treated “as [a] tourist trinket, and only recently as art or fine art.”

Out of this progression grew a wider acknowledgement of the influence of Native American art traditions on some of America’s most famous artists. It has been suggested, for instance, that Jackson Pollock’s “drip period” borrowed technique and choreography from Navajo sand painting. Likewise, Dale Chihuly mimicked designs for his glass “Baskets” series directly from his personal collection of weaving and basketry by Native American artists from the Pacific Northwest. Still, Nampeyo’s influence outside the Native art world remains “minimal,” according to Clarke.

When I asked him how he thought Nampeyo has been covered in art history, he pointed to a conspicuous lack of analysis around the context of her art practice. “It’s much easier to appreciate the aesthetic object rather than acknowledge that it was America’s own hunger for land, resources and ethnocentric biases that ‘shaped’ Nampeyo’s work.”

He’s right. Few writings on the Hopi ceramicist’s masterpieces delve into the drastic changes visited on Native peoples in the late 19th and early 20th century. Indigenous resistance to the 1887 Dawes Allotment Act, which accelerated the theft of tribal landholdings, exhausted already-scarce resources in Native communities. This was also the era of the American Indian boarding school system, which harmed generations of families and depleted hope for reconciliation. Yet the Hopi never relented. At stake for the Nation was a communal way of life with its matriarchs at the helm. In 1894, leaders and chiefs submitted a petition to Washington demanding their traditions be respected and sovereignty upheld.

Things weren’t much better in the art world. Indian art galleries were managed by white Americans, and consequently, Native art began to revolve around the tastes of non-Native collectors. The skew notwithstanding, Nampeyo lucked out. Fewkes and collectors alike nurtured a cult of personality around her for their own benefit, but it catapulted her work to national attention.

In this tricky art market, Nampeyo ran a clever gambit, calculating that if her work stuck to a certain aesthetic mode she could turn the power dynamic in her favor. It worked. Collectors who prized her pottery for its acumen and finesse paid handsomely, and her ceramics secured a steady income for her family at a time when U.S. theft of Hopi land reduced many of its citizens to destitution.

On the downside, however, to cultivate marketable mystique around the objects they collected, some traders and ethnographers were in the habit of characterizing Native artists in derogatory, racist terms, particularly when it came to artists whose prowess in their craft exceeded ordinary finesse and breached the hallowed grounds of fine art.

Of course, Nampeyo transcended those abusive labels. She was an artisan, an artist who tested the limits of her medium and mined inspiration from clay shards strewn across Hopi soil. The land was both teacher and wellspring of inspiration. Perhaps this is why her pottery feels as if it has been plucked from the earth fully formed.

Clarke’s insight into the political context of Nampeyo’s ceramics extends right up until today with an equally electric charge.

It’s difficult to gaze at the collected water jars (circa 1890) adorned with oily black eagle wings without considering the status of fresh water in Native America today.

Many in the Hopi Nation lack running water, and Natives number disproportionately among the nearly 1.5 million Americans without complete plumbing and sewer systems. Figures from water-stressed regions of North America are particularly troubling. According to a report by the American Association of Geographers, “Nearly three-quarters of households in an area of northern Arizona that includes five Native reservations lack connected plumbing.” As in the 1890s, so too today.

Yet Native Americans are fighting for their land, their sovereignty and their right to stewardship. In the past few months, Native water protectors, along with their allies in the “Stop Line 3” campaign, have worked to block the construction of a pipeline in Minnesota that would carry nearly a million barrels of tar sands from Alberta, Canada, to Superior, Wisconsin, every day. The Ojibwe environmental activist and economist Winona LaDuke has characterized the pipeline as “a crime against the environment and Indigenous rights.” (Bitumen-rich tar sands are petroleum’s dirtier cousin, partly because they’re more prone to spills than conventional crude.) First Nations peoples in Canada (i.e. Wet’suwet’en, Elsipogtog and Mi’kmaq) and Native Americans (i.e. the Standing Rock Sioux, Navajo and Gwichʼin) have been locked in similar battles with the petrochemical industry over proposed oil prospecting for years.

It was this spirit of pride and principled rebellion that Clarke referenced when I asked him how Nampeyo has influenced his practice as a Native American artist.

“While I love the harmonious forms and complex designs of her work,” Clark wrote me, “it is her dedication to family and community that inspires me. She managed to create such beauty in spite of the social/political context of the time. Nampeyo’s work is an expression of resilience, perseverance and resistance.”

“Nampeyo and the Sikyátki Revival” shows at the de Young Museum until Feb. 26, 2023. The museum is open 9:30 a.m.-5:15 p.m. Tuesdays-Sundays, and general admission is $15. The first Tuesday of every month is free to visitors, and Saturdays are free to Bay Area residents of all nine counties. Bring a driver’s license or piece of postmarked mail for proof of residence. For more information, visit deyoung.famsf.org.

Thank you so much for this magnificent article. My wife and I have always had a deep admiration and love of her work. She is so focused in her photographs, just working and creating away. It was revelatory to hear more about the challenges she had to create her pottery, and the social and political pressures surrounding her tribe while she was actively creating. She has always held a special place in our hearts and souls. Reading this has enabled us to have, perhaps, gotten to know her a little better as a wonderful human being on all four levels of existence–physical, emotional, spiritual, and mental.

Thank you for this brilliant essay, sensitive, informative, and wise. I have always admired the work of Nampeyo but I until now had not understood the full context of her work. Thank you!