At least six California community college districts suspect they have given out financial aid to fake students who have enrolled at their colleges this year.

At a minimum, the breaches represent a loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars to scammers seeking financial aid from California’s community colleges. It’s possible that much more money was delivered to fake students, given that the system’s 115 traditional colleges, enrolling about 1.8 million students, are in the midst of distributing more than $1.6 billion in federal Covid relief aid.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of the Inspector General is currently investigating the scam in California and nationwide. A spokesperson for the office declined to comment about the status of the investigation.

The statewide chancellor’s office overseeing the colleges starting in September has also asked each college district to report each month the number of suspected and confirmed incidents of financial aid fraud. The system declined to release the data it has gathered from the districts.

“At this time we are not providing these records, as they relate to an ongoing investigation and the strengthening of our security systems,” Rafael Chávez, a spokesman for the chancellor’s office, wrote in an email.

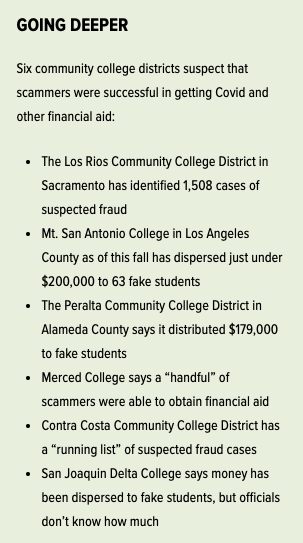

EdSource surveyed districts across the state and, among those that responded or agreed to interviews, six of them acknowledged that scammers were successful or likely successful in getting financial aid.

Some districts, such as the Los Rios Community College District based in Sacramento, are currently only classifying the findings as “suspected” fraud because, according to district spokesman Gabe Ross, the fraud only becomes confirmed “when a perpetrator is convicted or reaches a plea agreement through the federal investigation and adjudication process.”

Scammers have targeted federal aid, such as Pell Grant awards, and have also sought federal Covid-19 emergency relief grants, Ross said.

The scammers typically start by enrolling at a college using “either stolen identities or by recruiting individuals who provide their personal information in exchange for a cut of the financial aid proceeds. They then apply for financial aid in the student’s name via the FAFSA process,” Ross said, referring to the Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

Ross said the Los Rios district has identified 1,508 incidents of suspected financial aid fraud. The district is home to four colleges in the Sacramento area: American River, Cosumnes River, Folsom Lake and Sacramento City.

Merced College is also among the institutions that have unknowingly given out money to fake students. About 3,000 fraudulent students have tried to enroll at the college, and a “handful” of those scammers were successful in getting aid, said Michael McCandless, Merced’s vice president of student services. The college did not specify exactly how many.

Mt. San Antonio College in Los Angeles County had disbursed $190,732 to 63 fraudulent students as of October, according to college spokeswoman Jill Dolan.

The Peralta Community College District, which has four colleges in Alameda County, acknowledged this fall that about $179,000 in aid was distributed to fake students.

To keep scammers from getting their hands on more aid, colleges have been trying to identify bogus students as quickly as possible, often by looking for red flags such as multiple applications submitted from the same IP address or listing the same phone number.

The scam attempts are coming at a time when the community colleges are flush with cash from three federal Covid relief packages. The colleges have been awarded about $4 billion in relief aid, about $1.6 billion of which is being targeted to students.

“The awards that they’re looking at are pretty significant,” McCandless said of the potential award amounts the scammers receive.

What makes the community college system particularly susceptible to fraud, McCandless added, is that they accept anyone who applies.

“It’s great because we are trying to eliminate those educational barriers for potential students,” he said. “But at the same time, if you are interested in fraud, we are a great target.”

Contra Costa Community College District, which includes three colleges, has a “running list” of suspected incidents of money being distributed to bogus students, said Kelly Schelin, associate vice chancellor of educational services at the district. The district is pursuing each case to confirm that the money was fraudulently obtained.

At Delta College in the Central Valley, administrators “believe that some amount of financial aid money has been disbursed to fraudulent students,” said Alex Breitler, a spokesman for the college. “Because the investigation is still ongoing, it’s premature to share any possible numbers on the total amount.”

To prevent scammers from getting aid, colleges need to be able to identify the individuals involved. Some colleges have had more success with that than others. College of the Canyons in Santa Clarita, a city in northern Los Angeles County, has dealt with financial aid scam attempts in the past. In 2013-14, scammers tried to enroll in the college to get Pell Grants, the federal financial aid awards, said Jasmine Ruys, the college’s vice president of student services.

Since then, the college’s financial aid office has kept a close eye out for “red flags,” Ruys said. Sometimes, multiple students with different last names but the same physical address will try to enroll. Or there will be multiple applicants with the same email or IP address.

“Other times there are people who are randomly picking classes, and not as a program of study. So if they’re taking welding and culinary and history of theater, we’re like, none of those classes go together. What’s happening here?” Ruys said.

When the college notices such abnormalities, staff members call the phone numbers listed on the applications. Typically, they never hear back from those students and are thus able to confirm that they’re not real students. Officials acknowledge that the verification system does put real students at risk if they don’t return those phone calls.

Other colleges said they have similar processes for spotting fake students. McCandless, the Merced vice president, said the college at one point this year came across 2,200 suspicious applicants and contacted each of them. “We only had one student call back and say, ‘Hey, I’m real,’” McCandless said.

Faculty also play a role in identifying the scammers. In a memo distributed this fall to academic senates across California’s 73 community college districts, the statewide chancellor’s office urged faculty to do what they can to verify that the students enrolled in their courses are legitimate students.

“Verification should take place through regular and effective contact between the instructor and students, such as class attendance, class participation, direct engagement with the instructor for asynchronous courses, completion of assignments, or general communication through any medium,” reads the memo.

The memo encouraged faculty to check work submitted by students to make sure it matches the subject being taught; hold regular office hours and encourage attendance; and “proactively reach out to students” who aren’t engaging in coursework.

Wendy Brill-Wynkoop, president of the Faculty Association of the California Community Colleges, said faculty have to be careful when dealing with students who aren’t engaging in class, especially during online classes. A student may appear to be fake if they haven’t participated in class, but oftentimes that student has a legitimate reason for not participating. They may have a work conflict, or they may simply be shy or not feeling well, Brill-Wynkoop said.

“We’re trying to be sensitive and student-centered. And then the challenge is trying to make sure that we don’t overcorrect so that we’re letting fraud through,” she added.

Another part of the solution to keep out scammers, college administrators say, is to update and modernize CCCApply, the central application portal for California’s community colleges that many scammers have been able to bypass because it required very little personal information to enroll. Applicants were able to create an account by checking boxes indicating they have no social security number or by declining to provide one. Applicants could check a box as homeless and not provide a permanent address.

The state chancellor’s office is taking steps to tighten the portal’s security. In July, the chancellor’s office installed anti-bot software on the portal. This fall, the chancellor’s office reported that the software detected that 20% of traffic on the portal was bot-related and that the new software had stopped 15% of it.

Beginning in December, the chancellor’s office plans to pilot multifactor authentication whenever a new account is created on the portal, a process that will require users to provide more proof of their identity beyond a username and password.

And ahead of 2022 budget negotiations, the chancellor’s office has asked for $7.63 million from the state to further overhaul the application portal.

McCandless, the Merced vice president, said improving CCCApply is the easiest way to reduce fraud.

“You’re never going to eliminate fraud, but the best way to significantly reduce this is by doing so on the upfront side and making it a lot more difficult before they get to the individual institutions,” he said.