Formerly incarcerated students who wrote letters to their teachers — describing their hopes and dreams, asking for a second chance — were less than half as likely as their peers to return to jail, a Stanford University study found.

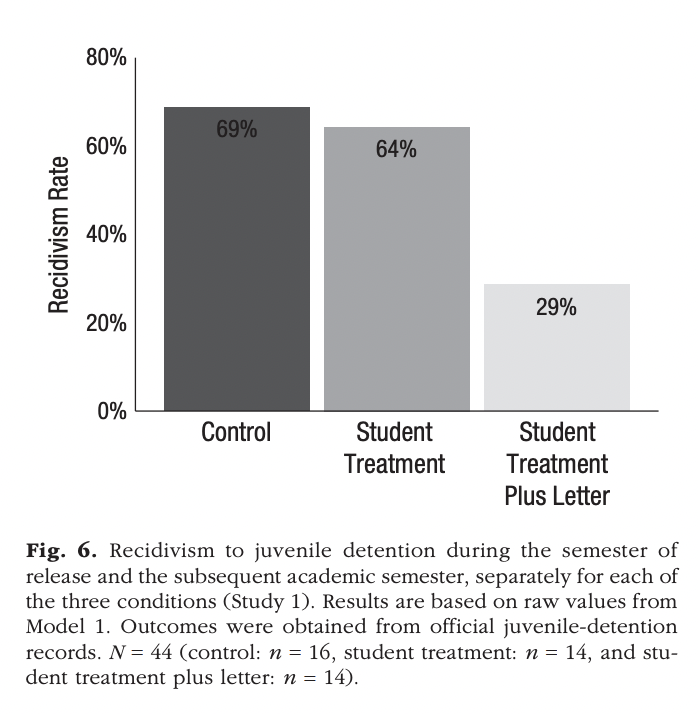

Researchers spent two years working with about 50 students in Oakland Unified who had spent time in the county’s juvenile justice system and had recently returned to their regular schools. Researchers asked the students to write personal letters to their teachers. Half the letters were delivered to the teachers, and half were not. The recidivism rate among students whose letters were delivered was 29%. For students whose teachers did not see the letters, 69% ended up back in jail.

“The letters helped teachers see beyond the stereotype. These were individual children in difficult circumstances who were asking an adult for help,” said Gregory Walton, associate professor of psychology at Stanford. “Ultimately, it’s all about love.”

The research underscores the importance of strong relationships between students and teachers, which can benefit students of all backgrounds but is especially crucial for those who’ve spent time in the juvenile justice system, Walton said. Those students tend to feel isolated and stigmatized, and many experienced trauma in their younger years.

Students in the letter-writing group also had fewer discipline issues, the study found.

In their letters, students addressed their goals, what they need help with, and what they’d like their teacher to know about them. Responses included:

“(I’d like the teacher to know) I’m a good kid and likes to learn new things and like to have fun and I like talkin alot.”

“I do work & it good quality it just that I have a problem with being consistent so I need help & my grades are important.”

“I’m a smart person when it comes to math but I haven’t really been to school so it’s kinda hard to focus.”

“I would want her to know that my only goal in school is too build positive relationships & just to show everyone that I try my best & that I would try on my own before I ask for help.”

“I need more 1 on 1 time with the teacher because I don’t learn as fast as other kids.”

The results of the study were no surprise to Hattie Tate, an administrator in Oakland Unified who co-authored the study and leads the district’s transition program for students leaving the juvenile justice center. She’d been practicing similar techniques in Oakland schools for decades and had seen countless students turn their lives around.

“Having an adult who believes in them, who wants them to succeed, can change their whole attitude about learning,” Tate said. “It creates a sense of belonging at school. That’s not something they’re used to, and they just thrive when they feel it.”

Tate typically starts each semester with a “welcome circle,” where students sit in a circle with their teachers and talk about their goals. Throughout the school year, teachers spend plenty of one-on-one time with students to get to know them personally and check in on their well-being daily.

She focuses on five tenets: self-awareness, self-control, social awareness, building relationships and making responsible decisions. Apologies and forgiveness are also part of the daily routine.

Although they lack the credits to apply for California’s public universities, Tate’s students often graduate from high school, enroll in trade school or community college and sometimes transfer to four-year universities. At least one of her former students graduated from UC Berkeley.

“Anyone who’s been successful in life has had adults who’ve inspired, motivated, pushed them,” Tate said. “These students are no different. By having these strong relationships, they learn that they can be successful in spite of whatever trauma they’ve gone through. It’s like, ‘Wow, someone believes in me.’ ”

“I’m a smart person when it comes to math but I haven’t really been to school so it’s kinda hard to focus,” wrote one student in a letter to a teacher.

One of Tate’s former students, Juan Campos, said that approach saved him from becoming entangled in gang life or worse when he was a high school student in Oakland in the late 1990s. He had moved from Mexico to California at age 8 with his family, and he struggled to find stability. The family moved a lot, his parents worked almost constantly, and school was not a priority, he said. Becoming involved in gangs, like many of his friends were, seemed inevitable.

“Fortunately for me, my gym teacher, my English teacher, and Ms. Tate believed in me,” Campos said. “They saw something in me, and they pushed me. I feel incredible gratitude for that.”

Campos’ English teacher visited Campos’ home and talked to his parents about why their son should go to college. Without that personal plea, Campos’ parents never would have understood the importance of higher education or that their son could attain that kind of academic success, Campos said.

Campos went on to Laney Community College in Oakland and California State East Bay, graduating with a degree in psychology. He now works as a case manager at an Oakland nonprofit that focuses on youth violence prevention. Every day, he works with young people who are experiencing the same struggles he faced.

“I know, from my own life, the importance of good adult role models and strong relationships. It’s absolutely crucial,” he said.

“I would not be where I am right now if those teachers had not believed in me. Now I try to provide that for my clients.”

For Michael Harris, a senior director of the National Center for Youth Law in Oakland, which participated in the study, the most important part of the Stanford study was what it revealed about teachers’ biases. Even teachers who were well-intentioned tended to disregard the potential of students who had been incarcerated — at least at first, he noted. It took a personal letter from those students to change teachers’ minds.

“There are stereotypes that exist among educators, but this study tells us that it’s not the end of the road. Those biases can be overcome, and those teachers can still form strong, positive relationships with their students,” Harris said.

He also noted how little it took to change students’ trajectory.

“It’s a very low-cost intervention. We’re talking about a letter to a teacher,” Harris said. “But what incredible results.”

While the letter-writing is important, day-to-day positive interactions with adults is also key, said Y’Anad Burrell, executive director of Youth Uprising, an East Oakland nonprofit youth center that helped with the research. Efforts to improve students’ lives must be consistent and predictable, so students know that school is a reliably safe place, she said.

“This daily repetitive positive influence in students’ lives keeps them away from engaging in activities that will push them back into the criminal justice system,” she said.

The study, published by the Association for Psychological Science, also outlined other ways teachers can make students feel welcome in class. Researchers from UC Berkeley, University of Michigan and Ohio State, along with staff from Oakland Unified, helped with the study, which Walton plans to expand to San Francisco Unified and Sacramento City Unified.

Walton acknowledged that despite the positive results, nearly 30% of the students in the study did return to jail, some as soon as the next semester.

“It’s not a panacea. There’s no cure-all,” Walton said. “The question is, how do we make progress?”