Living on a hill near a gravel pit in Draper, Utah, Adrian Dybwad can see the dust rise from the pit when a strong wind blows.

“I just wondered how much dust was generated,” he said.

His curiosity led him to create air quality sensors and the website PurpleAir, which shows air quality at the neighborhood level. The sensors will measure and report particulate matter from, among other things, wildfire smoke.

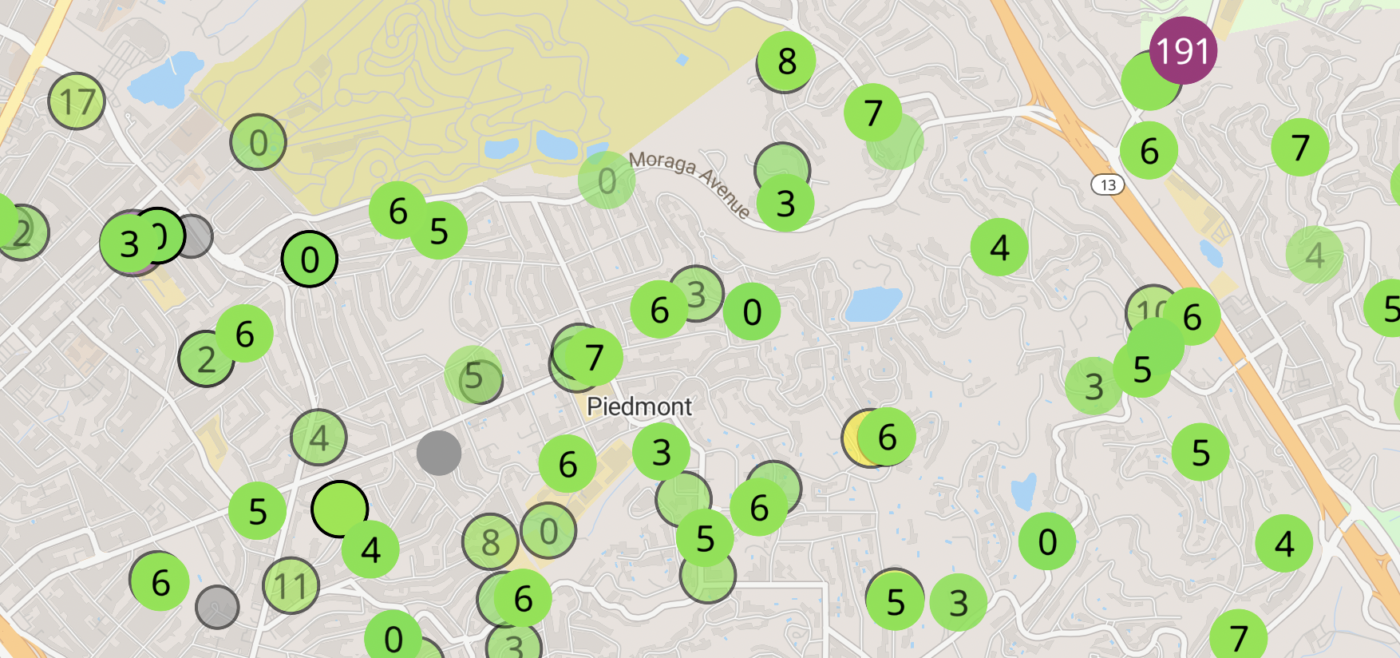

PurpleAir has about 500 sensors in Oakland and nearby areas like Piedmont and Emeryville, compared to the Bay Area Air Quality Management District, which has three of what it calls monitors in Oakland and seven monitors in total in Alameda County.

Air district monitors operate on a more regional scale and take longer to report results, Dybwad said in an interview. PurpleAir sensors report air quality in real time, he said.

“Air quality can change very, very quickly, he said, arguing that PurpleAir sensors allow residents to choose where to go for the day, school administrators to decide whether to open schools and businesses to decide whether to keep employees at home.

But PurpleAir sensors, which can be bought by residents and businesses, are less accurate than government monitors, Dybwad acknowledged. They typically overestimate the pollution in the air, he said.

The air district agreed.

Still, the difference is not large, Dybwad said. It is between very poor air quality and poor air quality, not poor air quality and good air quality, he said.

Air district officials also agree that PurpleAir sensors “can provide important information about real-time air quality” at the neighborhood level.

“Residents can leverage the density of these sensors to better understand how air quality is changing in their neighborhoods and how air quality can rapidly change over short time-periods,” air district spokeswoman Kristina Chu said by email.

“In areas where there is not a nearby Air District site, a denser network of low-cost sensors can provide helpful information to local residents,” Chu said.

But the difference between the air district’s monitors and PurpleAir sensors is especially pronounced during episodes of wildfire smoke, she said.

“These low-cost sensors are not only susceptible to differences in how each user deploys or maintains them, but each sensor can have different responses to the same levels of PM (particulate matter or pollution) due to changes in humidity, temperature and the type of particulate matter in the air (wildfire smoke vs. typical PM pollution).”

“Accuracy can vary greatly from manufacturer to manufacturer, and from sensor to sensor, and can change over time,” Chu said.

But Dybwad said residents who use PurpleAir sensors can develop visual and otherwise sensory knowledge of air quality and its relationship to PurpleAir readings.

PurpleAir sensors are low cost so individuals or groups can purchase one and place it outside or in a home or other building. Prices range from $199 to $279.

The results are reported over Wi-Fi and are available to anyone who can call up the PurpleAir map, which can be found at https://map.purpleair.com/.