For Richmond’s Nystrom Elementary School, students’ longstanding struggle with reading is not only an academic issue but one about civil rights.

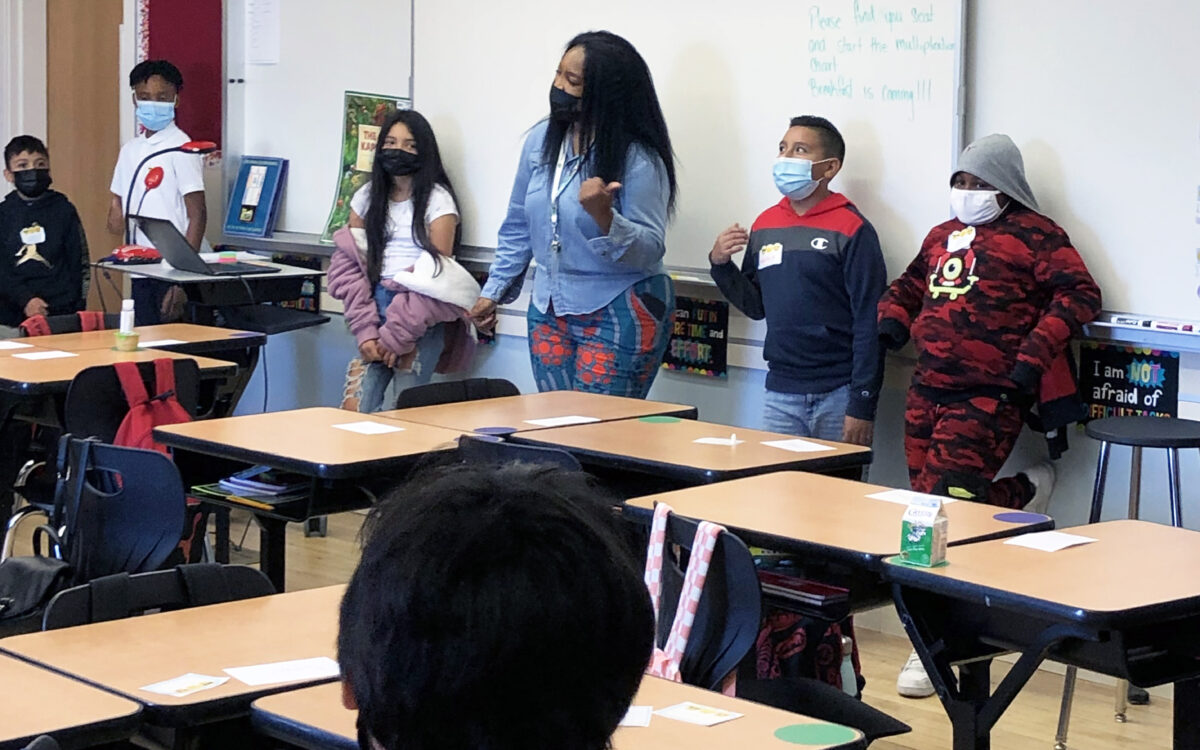

The Bay Area school began the year with a proclamation that acknowledges that systemic racism has led to disproportionate outcomes in reading skills for children of color for generations. It asserts that every student is capable of reading and that it’s the school’s responsibility to ensure every child leaves Nystrom a skilled reader. The school committed to overhauling its literacy program with a new curriculum and research-based classroom practices in an effort to bring every student to grade-level reading.

“When you think about equity, reading and literacy instruction has to be tied to that,” said Jamie Allardice, principal of the school, which comprises mostly Black and Latino students in one of the Bay Area’s poorest ZIP codes.

“If we are having kids leave Nystrom unable to read or read at grade level, we need to do our job better.”

The school’s plan this year has a greater emphasis on phonics in lessons and one-on-one intervention, as well as in classroom discussions and culturally relevant texts.

During the 2018-2019 school year, only 19.34% of Nystrom’s third through sixth grade students tested at grade level or above in English language arts on the state’s Smarter Balanced tests. That was up from 13.34% in 2017-2018. But it was still far below the average for California, where 51.1% of students in third through 11th grade tested at or above grade level for English language arts in 2018-2019. West Contra Costa Unified, as a whole, only had 35% of students testing at grade level or above in English language arts that year.

California has long been challenged by its low reading scores, as well as with disparities between low-income and Black and Latino students and their white and wealthier classmates. The latest effort to change this inequality is an initiative by State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond and lawmakers to get every third grade student reading by 2026. Research shows that students who aren’t reading at grade level by the third grade will struggle to catch up throughout their education career.

How Thurmond’s lofty goal will be accomplished is yet to be determined. He’s forming a task force of educators, parents and education experts that will make policy recommendations, which Assemblywoman Mia Bonta, D-Alameda, will propose in a bill for the upcoming legislative cycle.

Thurmond’s initiative follows the 2020 settlement of a lawsuit filed on behalf of students who struggled with reading at three elementary schools. The settlement rewarded 75 elementary schools across the state a total of $50 million in state block grants for literacy coaches, teachers aides, training for teachers and reading material that reflects the cultural makeup of the student population. Nystrom is one of the elementary schools included in the block grant, and has used the funds to pay for teacher training over the last year.

Because Nystrom’s reading performance lagged prior to the pandemic, Allardice said he’s shying away from the “learning loss mindset,” or the idea that students’ academic progress slowed or reversed during the pandemic.

“I feel like the learning loss terminology puts the onus on the kids,” Allardice said. “They’re saying the kids have lost something, but in many cases, it’s not the kids, it’s we as adults who need to do better for our kids.”

Allardice said teachers conducted DIBELS assessments to determine students’ literacy skills. DIBELS stands for Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills and consists of grade-specific assessments, such as naming letters for kindergartners and reading aloud for sixth graders.

The results of the assessment, Allardice said, showed a clear need for more “explicit and systematic foundational skills instruction” than the school was previously providing. Foundational reading skills include phonics, the ability to decode words by correlating sounds with letters or groups of letters, as well as to derive meaning from them through language comprehension. Teachers will up their instruction and practice opportunities for foundational skills from 10-12 minutes a day to 30 minutes a day, Allardice said.

Teachers will also be doing “targeted work” to help build students’ reading skills, which are often “discreet” and require one-on-one attention.

The assessments will continue at the end of each trimester to measure growth and identify whether adjustments need to be made, he said.

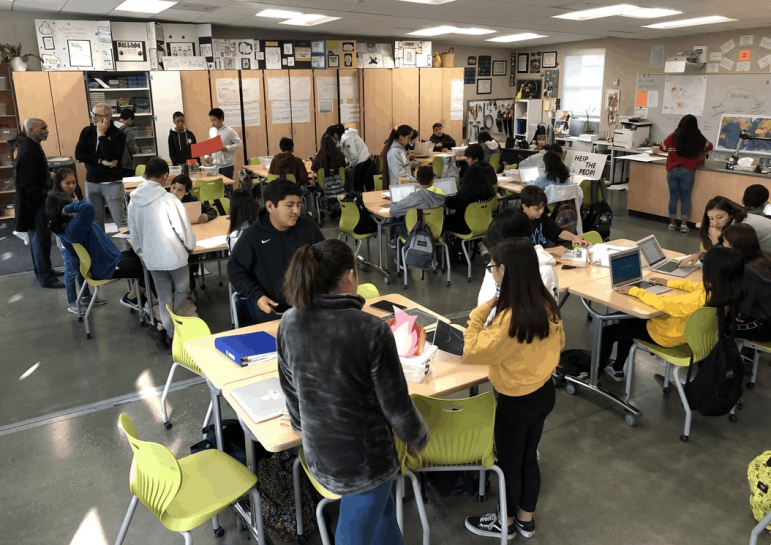

One of the biggest changes the school has made was switching English language arts curriculums from McGraw Hill’s Treasures — now available as Wonders — to EL Education. A major difference between the two curriculums is that EL Education has students reading high-quality books every day; whereas, the Treasures had students reading portions of books within an anthology. Each week was a new story, Allardice said, instead of “building knowledge of the world through meaningful texts and discussion.”

EL Education is open-source, meaning its instruction guides are available for free online — the only cost is for printed reading material. Four other West Contra Costa Unified elementary schools have also switched to EL Education, Allardice said.

EL Education takes the “science of reading” approach, which refers to a growing body of research on how children learn to read that calls for a phonics-heavy program. Nystrom will focus its literacy program on this approach, as are a growing number of schools seeking to move away from the “whole language” strategy, which focuses on growing a child’s love for literature. The decades-old disagreement between the two camps has been referred to as the “reading wars.”

The “science of reading” approach centers around the idea that learning to read is not a natural process like learning to talk. Instead, it comes from explicitly teaching children how to connect letters and words. The ability to decode words through phonics, as well as to derive meaning from them through language comprehension, is what makes a skilled reader.

Another benefit of EL Education, Allardice said, is its “content modules,” which have students reading grade-level texts while also doing activities that help build phonics skills through classroom discussion. He said the discussion aspect is particularly important for English learners, who make up 56% of the school’s students.

“Those opportunities to use and apply language are particularly important for English learners,” Allardice said. “We are a school with a lot of English learners, and we know that creating language-rich classrooms will increase their proficiency in English and develop biliteracy.

In light of calls across the country to focus more on phonics, researchers and advocates for students who are learning English as a second language have recommended that teachers also give English learners experience reading aloud, vocabulary lessons and lots of practice speaking.

Allardice said “it’s not an either/or” with phonics or language development; teachers will need to vary the amount of both according to student need.

Providing all students with grade-level texts on a daily basis will also be critical to getting students to grade-level standards during the next year, Allardice said. For example, he said, if a fourth grade student is reading at a second grade level, if they are only provided with second grade level texts, “that doesn’t do much to catch them up.”

“If we give students access to grade-level content, that will accelerate them more than the idea of remediation,” Allardice said.

Allardice said the school plans to feature “culturally relevant and responsive” reading materials during the year, courtesy of Student Achievement Partners — a national provider of classroom resources. Gloria Ladson-Billings coined the term culturally relevant teaching in 1994 as a teaching style that uses “cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning more relevant and effective.”

Third graders will start the year with a module that teaches them about what school looks like in different parts of the world. They will read “Waiting for the Biblioburro,” which takes place in Colombia, and “Nasreen’s Secret School,” which is about a girl in Afghanistan, Allardice said.

Fifth graders, for example, will read “Esperanza Rising” — an award-winning novel about a Mexican girl who immigrated to California to work in a farm labor camp during the Great Depression — alongside the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

“To see the kids analyze two texts and apply a novel like ‘Esperanza Rising’ to the UDHR is amazing to see, and the type of learning experiences I want for my kid,” Allardice said.