To simplify the often-confusing Covid testing process in schools, an increasing number of districts in California are turning to “pool testing” as a way to save time, reduce hassles and keep students in school.

With pool testing, nasal swabs from up to 25 asymptomatic students are submitted together for a single PCR test. If the test is negative, the entire class is assumed to be Covid-free. If the test is positive, students are given individual rapid tests, and those who test positive are sent home to quarantine. Others in the class can continue attending school as long as they test negative twice a week.

Administered weekly, pool tests are an efficient way to catch outbreaks on campus with minimal impact on parents and teachers, public health experts said. As with many other Covid test options, the state pays for pool testing for schools.

“Pool testing is a very good screening tool. It saves time; it saves money; it can even be self-administered. Anyone can do it,” said Dr. Karen Smith, former director of the California Department of Public Health under Gov. Jerry Brown.

“Many schools are in a period of confusion right now about testing. I hope more of them become aware of the free testing programs, such as pool testing, available to them.”

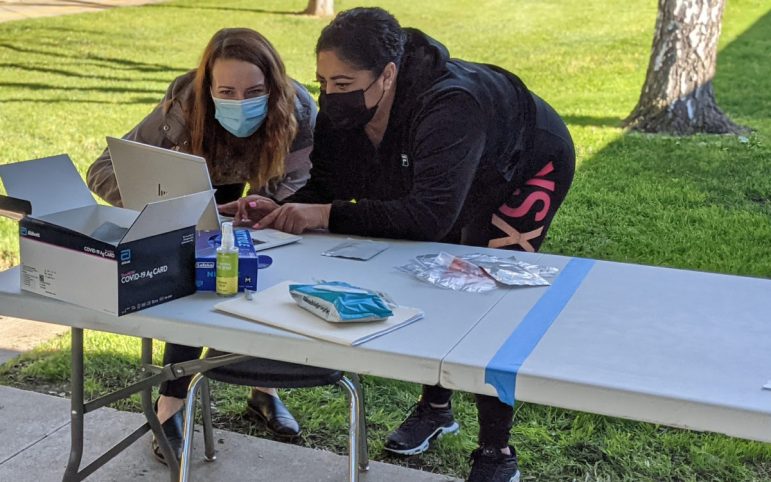

Pool testing is among the free testing options the California Department of Public Health and Department of Education are offering for schools. The state has contracted with Concentric, a public health division of Boston-based biotech firm Gingko Bioworks, to conduct the pool tests and help schools streamline the process.

At least 700 schools in California have signed up, and more are enrolling daily, said Laura Bronner, who oversees California’s pool testing for Concentric.

“It takes a little upfront work, but for most schools, it’s an easy, free way to keep classrooms open and keep students safe,” Bronner said. “No test is perfect, but this is a good first step.”

Testing, along with mask mandates, vaccinations and quarantines, is a key way that schools can monitor Covid outbreaks on campus. But test shortages and confusion about protocols have hindered testing efforts in many districts, especially as more students are placed in “modified quarantine,” which allows students to stay in school even though they’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive, as long as they’re asymptomatic and test negative for Covid twice a week.

Rapid tests, which can yield results in 15 minutes, are in short supply in some areas and can be less accurate than PCR tests. Individual PCR tests, on the other hand, can take several days to produce results, which means students are quarantined at home for longer periods.

Pool tests require parents’ consent, but otherwise entail minimal paperwork because the tests are anonymous and done in bulk. Instead of 25 forms, staff members only need to fill out one.

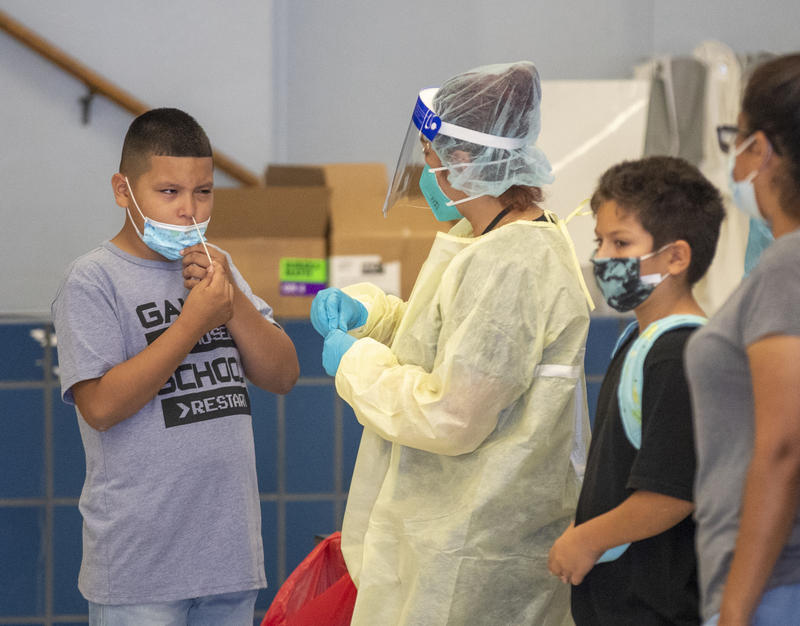

The testing process is straightforward. Students administer the nasal swabs themselves, four turns in each nostril, and place the swabs in a large tube that’s sent to a laboratory for testing.

“We tell kids, if you can pick your nose, you can self-swab,” Bronner said. “If you can make it fun, it’s a lot easier.”

Students who have symptoms, even if it’s just a sniffle, are not included in the testing pool. Instead, they’re given a rapid test or sent home, or both.

Elementary students are usually tested with their classmates, in cohorts between five and 25 students, and high school and middle school students are tested during a specific period or class. School sports teams can also participate in pool testing. Whether a student or teacher is vaccinated doesn’t affect their ability to participate.

Administering the test and gathering the swabs takes less than 10 minutes, Bronner said. Results typically arrive within a day or two.

In the spring, a study of pool testing among schools in Massachusetts showed that fewer than 1% of classrooms tested positive for Covid, and pool testing was a key factor in schools remaining open for in-person instruction, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker said.

California’s results are likely to be a bit higher because of the surging delta variant and a bump in Covid transmission due to schools reopening, Bronner said.

Anderson Valley Unified in Mendocino County administered its first pool tests on Sept. 8, about three weeks after schools opened. Prior to the pool test, students and staff were tested at a community health clinic.

About 200 students and staff opted into the district’s pool test, slightly less than half of those who are eligible, although Superintendent Louise Simson expects the number to climb as more families learn about the program. Concentric sent two nurses to administer the tests at every campus in the district, plus the district office. The whole process took less than four hours.

Results came back the next day. None of the pools were positive.

“It’s amazingly reassuring,” Simson said. “This seems like the most efficient way to test large groups of people without taking up more than a few minutes of instructional time. It provides a really good overview of community health. … It’s a way for us to drive our own ship.”

A potential downside to pool testing is if large numbers of parents don’t opt in, or if the infection rate is very high within a school or community.

In that case, the pool result has such a high likelihood of having at least one student who’s positive that it’s not a good indicator of the overall health of a classroom. Individual tests are a better way to track Covid outbreaks in those scenarios.

Another downside is that if the pool is large, the test may be less sensitive and miss a positive case, said Dr. Edwin Monuki, chair of the Department of Pathology at the UC Irvine School of Medicine.

“For this reason, pooling should only be considered in conjunction with a sensitive high-quality test,” he said.

Another drawback is the timing, he said. Pool tests might take longer than individual tests, and if a pool test comes back positive, the school loses more time when testing each student in the pool. The turnaround time could be double, Monuki said.

While pool tests can be an efficient and inexpensive way to keep students safe, schools should also prioritize other methods to curb the spread of Covid on campus, he said. Vaccines, masks, hand-washing, social distancing, flu shots and individual Covid tests “should be the standard” at every school, he said.

Mountain View Whisman School District in Santa Clara County has seen great success with its pool testing, said Superintendent Ayindé Rudolph.

“While vaccines are certainly America’s path out of the pandemic, districts everywhere need to embrace weekly testing to be able to track, trace and contain the virus within school walls,” Rudolph said. “It’s simple, it’s cost-effective and, most importantly, it gives families confidence. When we know our classrooms are virus-free, we can focus on providing nurturing learning environments for our children to grow — not the virus.”

Parents who’ve advocated for in-person learning also support pool testing.

“Pooled testing is a great tool to deploy when testing kids per (the California Department of Public Health) guidance on modified quarantines, that is, testing to stay in school,” said Megan Bacigalupi, a founder of Open Schools California, a parent group that has pushed for schools to reopen during the pandemic. “Many districts are experiencing testing supply shortages or lack of testing personnel, and pooled testing makes sense to help kids remain in school.”