A pang of hunger rattles his stomach, and he pauses to turn away from the crowd, resting the weight of his forearms on a wooden fence. His shoulders stoop as he slumps into himself. His eyes are hidden behind the brim of a sweat-hardened hat: a face in the throng. We’re denied full entry into this forlorn moment. Looking is permitted, but not intrusions.

Blending artistic acumen and sheer luck, “White Angel Breadline” (1933), one of Dorothea Lange’s most acclaimed photographs, is also one of the first she took on an excursion outside of her San Francisco studio. In it, she captures the worn face of a hungry man amid the hustle-and-bustle of a Depression-era breadline. It illustrates both her resistance to pathologizing the indigent and her refusal to portray them as pathetic or dirty, as many urban sociologists of her time did.

This ethos is typical of her work, and so is her ability to fully immerse her viewers in the worlds she visited. Every pixel is rendered with painstaking care and attention to granular detail. Her images linger on, stuck to you days after viewing them. The remarkable endurance of her photographs is matched by their remarkable legacy. Lange is one of the few photographers whose work remains immediately recognizable to many Americans more than 90 years after it was first published.

“Dorothea Lange: Photography as Activism” at the Oakland Museum of California showcases the work of a photographer of peerless caliber, craft and artistry. The exhibition curates 47 works from her oeuvre as well as two interactive displays on juxtaposition and cropping that make her genius more immediately apparent to the visitor. (Unfortunately, portions of the interactive displays have been removed as a precaution against the delta variant.)

The assembled images pay tribute to a woman who, in her quest to uproot social inequities by documenting them, examined much more than her famed Dust Bowl subjects. Visitors appreciate this tender attention to America’s underclasses and learn about a woman who devoted her professional life to capturing them on film.

Dorothea Lange (née Nutzhorn) was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1895 and raised in a second-generation German family that exposed her to artistic practice and the possibilities of art as a vocation from an early age. (Back in Germany, for example, three of her uncles owned a successful lithography business.) At 7 years old, young Dorothea contracted polio. Though the virus left her body after her fever broke, the paralysis it inflicted on her right leg never fully did. To her chagrin, she lived with a limp for the rest of her life.

It’s tempting to explain her affinity with the down-and-out as simply a result of her own experiences as a disabled woman, thereby reducing her artistic genius to stale biography, but it’s more than that. Her ambition drove her to take advantage of every opportunity she could find and every apprenticeship she could sweet-talk herself into.

It was years of this dogged pursuit of practical experience and informal training picked up from hobby photographers and professionals alike that allowed her to succeed in San Francisco, where she moved at the age of 24.

Soon after her arrival, she opened her own studio, and her talent gained her popular acclaim within city limits. Her work in portraiture, mostly of wealthy clientele, secured her middle-class prosperity.

History situates Lange in the tradition of documentary photographers like Lewis Wickes Hine and Jacob Riis, but what’s most remarkable about Lange’s images is the brand of unconditional sympathy — rare these days — they engender in the viewer.

Looking at “Migratory Cotton Picker, Eloy, Arizona” (1940), we see the leathery hands of a migrant farmer, and we sympathize. We’re unburdened by the baggage of our own prejudices about poor rural folk. We don’t wonder how he ended up picking crops or if he’s a gambler or a womanizer — none of that. The image effaces these concerns. He simply is. His personal choices are made irrelevant. Instead, Lange places him in the pantheon of hungry, desperate Americans whose lives have been shattered by dispossession, privation and generational trauma. We want them rescued from that vicious circle, these men and women who put food on American dinner tables and clothes on American backs. Dignity — and so much more — is owed to them.

Her work narrates history in a way that many textbooks cannot. At the time of photographing “Eloy” and the rest of the series, the United States had only begun to emerge from the ashes of the Great Depression. Regional crises plagued the nation. Southern plantation elites had, for years, taken to asset-stripping the once-fertile land without reinvesting any of the profit into education, physical infrastructure or social welfare. Their mismanagement of farmland and subjugation of Black citizens frayed the region’s social fabric. In the Midwest, meanwhile, the Dust Bowl had ravaged an estimated 100 million acres of land and turned 3.5 million Americans into what today’s commentators might call “climate refugees.”

Lange pulled apart these complexities and, in simple visual renditions, depicted what former secretary of agriculture and vice president to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Henry Wallace, called “human erosion”: the twinned erosion of land and people, of human capital and human life.

You can see it play out on the faces of her subjects: their sunbaked skin, their cracked smile lines and their unbending resiliency in spite of their bleak, inhospitable surroundings.

Her photographs showcase a knack for rendering complex social observations in two dimensions. She examined her subjects on their own terms with the aim of capturing intimate moments that inspire not pity, but sympathy. One exemplary photo is of a Black woman smiling coyly, seated in her chair, surrounded by dried tobacco leaves that encircle her feet like petals on a daisy. Everyday resistance to the plantation economy, Lange suggests, exhibits its own stark beauty. Similarly intimate moments of joy, unbowed pride and resilience in the face of daunting obstacles comprise the exhibition.

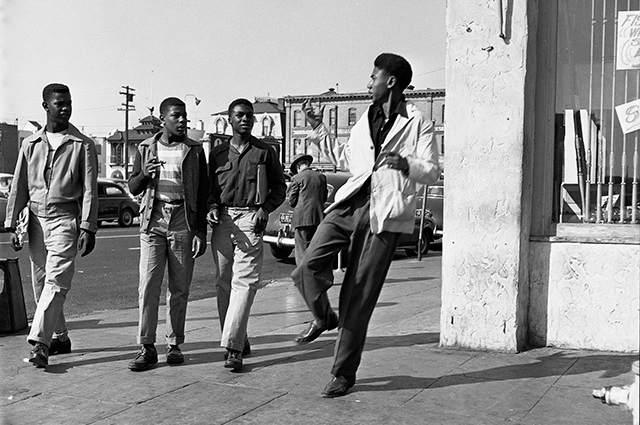

The images bring to mind the Movement for Black Lives which, since 2015, has focused its energies on highlighting “Black joy” and its “vision for Black lives.” Critically, organizers emphasize the importance of social change to all Americans. Securing Black lives, making them “matter” in all sectors of public life requires redirecting funds away from police and prisons and toward accessible education, affordable health care and democratic power. Whereas racist policy-making doomed the New Deal of Lange’s era to segregate the U.S., the Movement for Black Lives demands a rising tide to lift all boats.

Wandering through the exhibition, it’s hard not to wonder what demons chased Lange across her long, storied career. What must it be like to document squalor and destitution day in and day out, year after year? Did these images haunt her as they do their viewers? Photographers and cameramen suffer high rates of suicide, a fact that has long troubled the industry as the lives of many of the most promising artists have been snuffed out before their time.

The case of the celebrated South African photojournalist, Kevin Carter, exemplifies this phenomenon. Three months after winning a Pulitzer Prize for his “The vulture and the little girl” (1993), depicting an emaciated child making her way to a U.N. food station in Sudan while a vulture leers hungrily at her, Carter took his own life. At the time, the child’s fate was unknown, no doubt increasing his debilitating guilt. Carter’s life and his acclaimed image speak to the difficulty of bearing witness. Documenting trauma on such a vast and unknowable scale exacts a terrible toll on photographers.

The pictures at OMCA aren’t easy for the viewer to confront, either. Lange’s photographs nag at you. Like a splinter, they get under your skin and lodge themselves deep in your psyche. Brutal realities are laid bare, something that even her employers found difficult to stomach. (Her series chronicling the afterlife of slavery, racism and class warfare in the Jim Crow South “drew criticism” from her employers in the U.S. government, according to a plaque placed in the exhibit space.)

Here is a trail of mementos that lead us to an inevitable conclusion: We are still fighting the same battles we were in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

Yet, a specter of hope lingers. After all, it is images like Lange’s that have sustained the momentum of social movements and the calls for reparations over the decades.

Internment, for instance, remains an open wound for Japanese Americans, some of whom hold an annual vigil in San Francisco for the 120,000 men, women and children incarcerated during World War II. They have not forgotten what was done to their ancestors. Neither have the descendants of Black sharecroppers or enslaved individuals that Lange photographed. While some Americans may have shied away from this history, the overwhelming evidence of our country’s wrongdoing refuses oblivion.

Despite Lange’s enduring conviction that photography could function as a tool for social change, we shouldn’t be so naïve as to believe that simply viewing photographs of suffering sparks social change. Lest we forget that shortly after images began circulating of abused Iraqi detainees at the squalid Abu Ghraib prison in May 2004, many American pundits and commentators were quick to grasp for justifications, preferring instead to explain away the photographs as the crazed actions of “bad apples.” Few advocated the U.S. military admitting to and atoning for the horrors the images depicted.

Leaders, especially those with authoritarian tendencies, are inclined to challenge the integrity of images. They cover the lens of a camera, or they manipulate our trust in what we see. Stalin had the Glavlit to manage Soviet media, and Hitler hired Joseph Goebbels to do his bidding as minister for public enlightenment and propaganda.

But American presidents haven’t been immune to this impulse to control optics, either. In 1991, George H. W. Bush’s administration banned the press from snapping images of soldiers’ coffins returning home during the Gulf War, a policy that would stay in effect for 18 years. Donald Trump corroded public trust in the photograph each time he claimed his inauguration was attended by 1.5 million people, when in reality less than a third of this figure are estimated to have shown up.

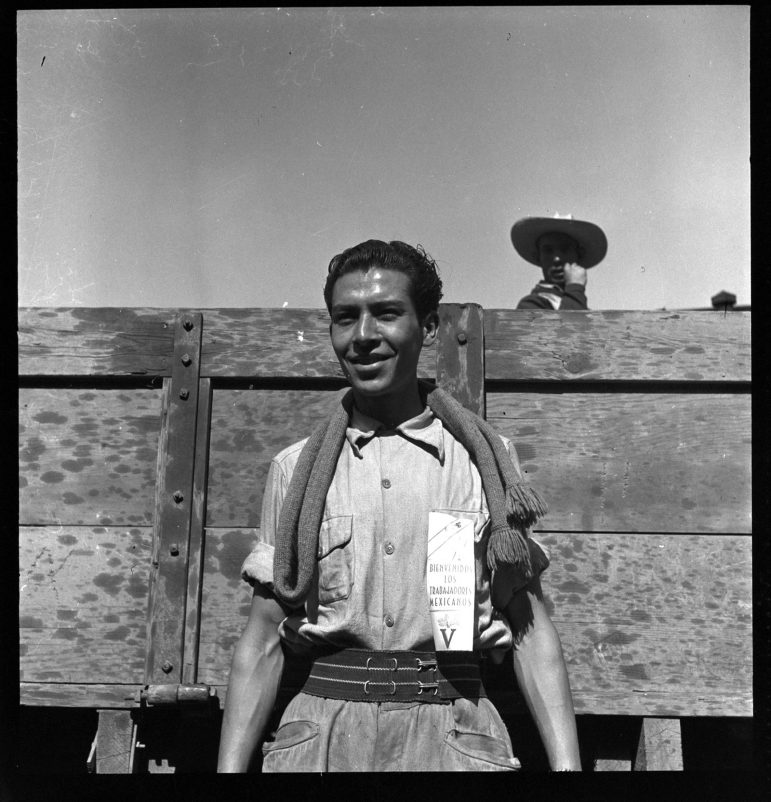

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California. Digitized for the Oakland Museum of California 2019 Luce Grant

In recent days, unfortunately, Joe Biden has proven susceptible to a similar tendency. When asked why more Afghans were not welcomed into the United States or given visas ahead of the U.S. military’s planned withdrawal from Afghanistan, he claimed that many “did not want to leave earlier,” despite a flurry of images of people wading through sewage water to get to Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport. (This is to say nothing of the backlog of 17,000 visa applications from Afghans, attesting to their desire to flee long before the Taliban seized power in Kabul mid-August.)

With Lange’s work in mind, it’s clear not only that photographs exert a unique psychic power that lends itself to radicalizing the viewer, but also that, at the end of the day, it’s up to that same viewer to actively engage with and credit what they see.

“Dorothea Lange: Photography as Activism” pieces together an honest appraisal of U.S. history that enumerates our nation’s cruel machinations, mistakes and missed opportunities. It chronicles the cycles of dispossession, impoverishment and harm that plague American urban centers and rural towns well into 2021. Turn on your TV, and images of the devastation proliferate. California is ablaze, as Louisiana drowns in seawater and a pandemic ravages the nation’s unvaccinated. It appears we’ve got our work cut out for us. Above all else, what Lange’s photographs capture is the unfinished business of social justice.

The exhibition will be showing at the Oakland Museum of California indefinitely. The museum is open 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Sundays, and general admission is $16. For those unable to visit in person, the museum also curates an extensive digital archive, which is available for browsing online.