Water plays a lead role in the state’s political theater, with Democrats and Republicans polarized, farmers often fighting environmentalists and cities pitted against rural communities. Rivers are overallocated through sloppy water accounting. Groundwater has dwindled as farmers overdraw aquifers. Many communities lack safe drinking water. Native Americans want almost-extinct salmon runs revived. There is talk, too, of new water projects, including a massive new tunnel costing billions of dollars.

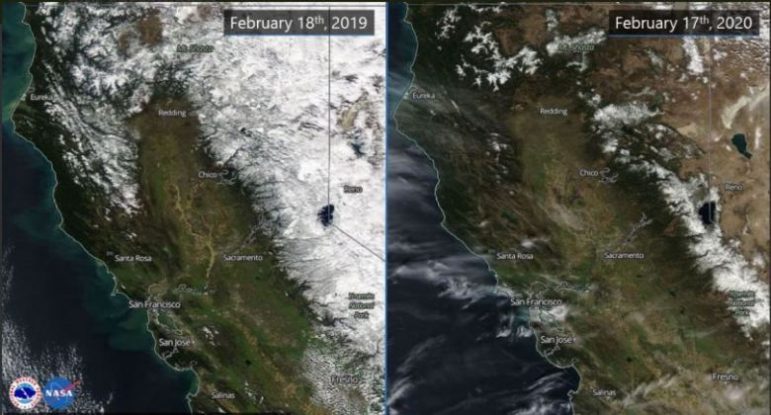

Scientists say climate change will bring more unpredictable weather, warmer winters and less snowpack in the mountains. These challenges and some ideas for remedies are outlined in a plan, called the California Water Resilience Portfolio, released by Gov. Gavin Newsom in early 2020 to a mix of praise and disappointment.

Below, an explanation of the state’s water development — as well as the challenges, today and tomorrow, of providing water for California’s people, places and wildlife.

Graphics by Elizabeth Castillo

This explainer was supported by a grant from The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism.

Where does our water come from?

It originates as rain and snow. Some falls in Oregon and drains into the Klamath River, and some falls in the vast drainage of the Colorado River. But most of it lands in California — about 200 million acre-feet on average per year. (An acre-foot is 326,000 gallons, what an average household consumes in between six months and two years.)

To understand what that volume means, imagine a skyscraper 38,000 miles tall. Yes, miles tall, not feet. Now, fill it with water. That is California’s average annual precipitation.

So, where does all this water go? More than half evaporates, leaving about 75 million acre-feet either frozen in mountains or filling rivers, lakes and reservoirs. Some sinks into the ground.

About half of the 75 million is diverted to human uses, and half is left in watersheds, what is referred to as environmental “use” of water.

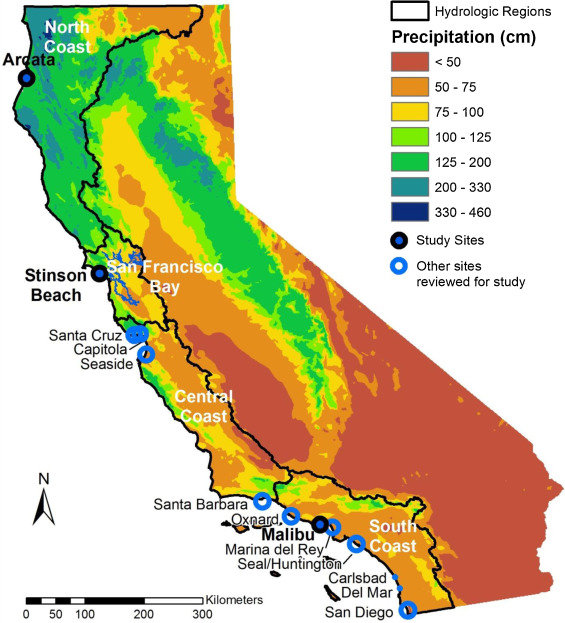

Source: Daniel J. Hoover, et al. Map of California showing the average annual rainfall from 1981–2010. Used with permission.

How does water get to us?

Because precipitation falls unevenly in California — almost ten feet per year drenching parts of the Coast Range and just several inches falling in deserts — water agencies have found ways to spread the resource.

A complex system of dams, reservoirs, pumping stations and about 2,000 miles of canals supplies water to Californians that originated in the Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Nevada and the Cascades.

For instance, when an 11-mile tunnel was drilled through the mountains of California’s North Coast in 1960, water that naturally flowed to the salmon streams and redwoods was diverted to San Joaquin Valley orchards and other farmland. This Trinity River project is one of many ambitious engineering projects that have brought water to Los Angeles swimming pools, San Diego lawns, Kern County crops and the taps of about 30 million people.

Here are our major delivery systems:

- The federal Central Valley Project uses 20 reservoirs and 500 miles of canals to send water from the Sacramento, San Joaquin and Trinity basins into the San Joaquin Valley and the Bay Area. It provides water for about 3 million acres of farmland.

- The State Water Project transports water via more than 700 miles of canals from the same river systems to cities and farms throughout the state, as far as San Diego. In all, it supplies 27 million people and 750,000 acres of farmland.

- Another 4 million acre-feet per year flow via a 242-mile aqueduct from the Colorado River to Southern California farmland and cities.

- Water from the Sierra Nevada travels via canals as far as 160 miles to San Francisco and surrounding cities, and Los Angeles imports it from the Eastern Sierra in a canal system more than 400 miles long.

- About 40 percent of all water used in California is pumped from underground basins in an average year. This share increases during drought years.

Source: California Department of Water Resources

How much water do we use?

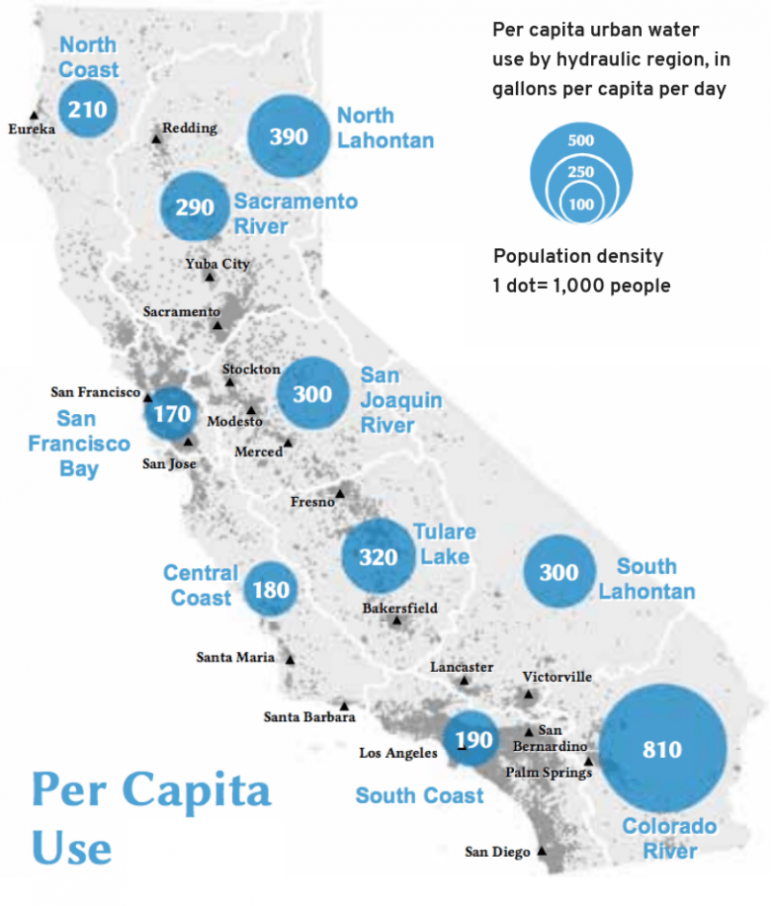

On average, each Californian used 85 gallons of water at their homes every day in 2016. By national standards, that’s right about in the middle. In Idaho, each person on average uses 168 gallons a day, the national high. Residents of Maine use the least, about 55 gallons.

Coastal city dwellers, especially in the cooler, rainier north part of the state, use the least water, while residents of inland suburban areas with spacious lawns, gardens and pools use much more.

In one water district in north San Diego County, each resident uses more than 500 gallons per day during the hottest summer months.

Source: California Department of Water Resources Water Use Balances for Planning Areas, 1998–2010 (Department of Water Resources 2014) and US Census Bureau (2010 population by Census Tract)

How much is used by homes compared to farms?

Even multiplied by 40 million people, the amount of water used by homes amounts to relatively little. Farmland uses three to four times more than people use for cooking, drinking, washing, gardening and landscaping.

California’s farmers and ranchers irrigate their land with about 30 million acre-feet of water each year (mostly from surface supplies but also from underground). Residential water use runs about 8 million acre-feet per year.

Another 40 million acre-feet or so flows through river systems, supporting wildlife. That’s on average, spiking in wet years and ebbing during droughts.

What are farmers growing with all that water?

Farm products generated $50 billion in sales in 2018, making agriculture the state’s most valuable industry. The biggest money makers are dairy, grapes and almonds.

Almond groves cover more than 2,000 square miles, mostly in the Central Valley. Because the trees occupy so much land — more than any other crop — environmentalists argue that they guzzle too much. They use an estimated 3 to 4 million acre-feet per year.

But other major crops require plenty of water, too. Alfalfa often uses more than 5 million acre-feet per year, although acreage has been declining. Open pasture for grazing takes up another 3 million acre feet or so. Rice paddies are annually flooded with almost 3 million acre-feet per year (though much eventually returns to the environment).

What are the environmental impacts of our water use?

In addition to economic prosperity, water diversions have brought environmental consequences.

Mono Lake, millions of years old, dropped 25 feet, nearly destroying its scenic ecosystem, when Los Angeles diverted the Eastern Sierra’s water. The San Joaquin River nearly dried up. Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy disappeared under reservoirs. And the Colorado River, in most years, is empty before it reaches its estuary at the Sea of Cortez.

Dams blocked migration routes of salmon and steelhead, and then diversions, levee construction and development created poor conditions for the surviving fish. Coho salmon, steelhead and green sturgeon are listed under the Endangered Species Act, and many salmon runs are expected to vanish this century. In addition, the tiny Delta smelt is almost extinct. The totuava, an ocean fish that can reach 300 pounds, once spawned in great numbers in the Colorado River Delta but is now scarce.

Much of the conflict over California’s water focuses on the Endangered Species Act. To protect species, pumping from the Delta is reduced. This creates strife between environmentalists and growers. Some biologists say more water needs to be left for river fish as well as San Francisco Bay creatures such as crab, herring and halibut.

Why is there so much talk about the Delta?

The Delta is where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet, east of San Francisco Bay. It is the hub of California’s water supply and conveyance system.

In an average year, pumps withdraw about 5 million acre-feet from the estuary. That’s about one-fourth of all the water that flows into the Delta. A pair of canals transport it to semi-arid regions, including San Joaquin Valley farmland and Southern California cities.

This use, combined with other factors like invasive species and water pollution, has strained the Delta’s ecosystem.

It’s not just fish that are in trouble. The levees are old and at risk of breaking, especially as sea level rises. A major levee breach could allow seawater to flood pumping stations, spelling disaster for farmers and millions of people.

Adding to the pressures is a recent pact to use less water from the Colorado River, which is divided among seven states. These battles are intensifying as demand increases and supplies shrink. This could force Southern California to look for more water from other sources, like the Delta.

Will a tunnel solve these problems?

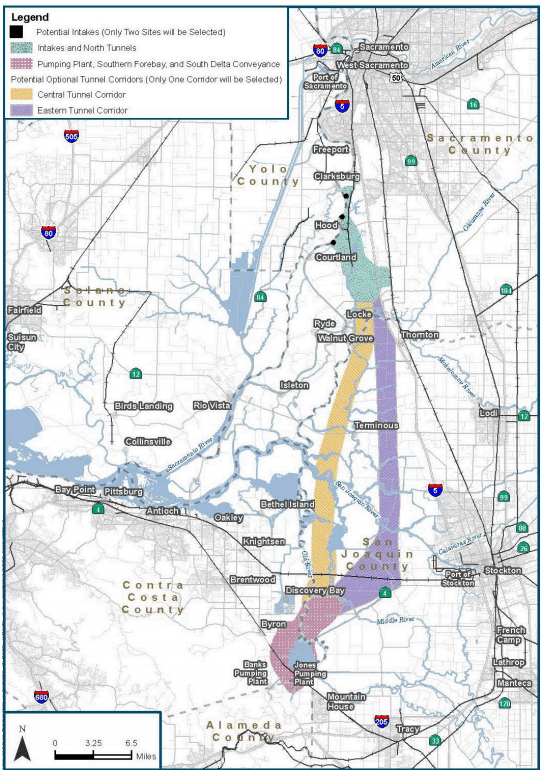

One proposed solution to the Delta’s water woes is to build a 35-to-40-mile-long tunnel that starts upstream of the Delta, near Sacramento, and routes water around the Delta before reconnecting with the southbound canal system.

Former Gov. Jerry Brown promoted a two-tunnel project for eight years without success. Newsom has downsized the plan to one tunnel and hopes to begin construction within three years.

Currently, major Delta pumps pull water from the heart of the estuary. This causes obstacles for migrating fish. In addition, the pumps are vulnerable to saltwater during low river flow and high ocean tides. A tunnel would shift water diversion miles upstream, which might alleviate these problems. Intakes would be several feet above present-day sea level, and the rivers would flow through the Delta and out to sea, which helps migrating fish.

But the tunnel plan is extremely controversial. Many opponents worry it could harm the ecosystem by diverting too much water before it reaches the estuary. Excessive diversions could also allow saltwater to threaten farms and communities in the Delta area that rely on freshwater. Moreover, moving the diversion point upstream to avoid rising seas simply kicks that can down the road a few decades.

The tunnel will cost an estimated $11 billion. Water suppliers, like the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, which supports the project, would likely cover the cost, although details remain unsettled.

Source: California Department of Water Resources

Can’t we just pump more groundwater?

Many farmers rely on groundwater, especially in dry years. Some Southern California cities also get as much as half of their supply from wells. But no California agency has been tracking exactly how much is used or who uses it, even though nearly every other state regulates this resource.

The free-for-all has led to farmers in many areas pumping groundwater faster than the natural recharge. Water tables have rapidly dropped and, in some communities, homes have run out of water. During the 2012-to-2016 drought, about 3,500 domestic wells went dry.

Also, when coastal aquifers are heavily tapped, saltwater creeps inland. In central and Southern California, water managers have to inject freshwater into aquifers to stop saltwater intrusion.

San Joaquin Valley farmers have pumped so much water that land in some areas have subsided by 20 feet or more. This damage cannot be undone, and the water storage capacity is lost forever.

Is there legislation to protect groundwater now?

Brown passed a triage of bills in 2014, collectively known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

The law requires local agencies to begin monitoring and regulating groundwater so that withdrawals don’t exceed inflow. But this stabilization will not happen anytime soon, since the law sets a sustainability deadline of 2040.

Many farmers are uneasy because it will reduce water supply and force land out of production. Some experts say farmers will have to fallow between 500,000 and a million acres. These changes are likely to hit hardest in the San Joaquin Valley.

Farmers have ideas to cope: One is to pay some not to grow anything and leave their water allocation for someone else. Another is to develop water markets to buy and sell water.

Are we facing another drought this year?

California entered 2020 almost bone-dry. And 2021 has been even worse. In July of 2021, 85% of the state is facing extreme drought.

Drought damages the environment and economy, particularly because the state still has not recovered from the 2012-2016 drought. Groundwater tables remain overdrawn, and with below-average Sierra Nevada snowpack, water reserves are unlikely to rebound anytime soon.

Is our water safe to drink?

Some of California’s aquifers, including large basins in the San Gabriel and San Fernando valleys, are contaminated with chemicals.

One of the greatest dangers is nitrates that leach from fertilizers, manure and sewage. Pesticides, oil waste, industrial solvents and other contaminants also pollute groundwater. The Community Water Center, a social justice group, estimated that more than one million state residents are exposed to unsafe drinking water each year.

In 2012 Brown signed into law AB 685, the Human Right to Water Act, which aims to bring safe, clean water to all Californians. Prop 1, a $7.5 billion bond passed by voters in 2014, allocated $520 million for clean, safe and reliable drinking water. Newsom signed SB 200, setting aside $130 million per year for a decade.

What if we just recycled more water?

In many communities, treatment plants collect used water, purify it and send it back into the delivery system, mostly for irrigation and industrial purposes. In 2015 California recycled about 714,000 acre-feet, primarily for landscaping and irrigation. Sixteen percent, about 114,000 acre-feet, was used to recharge groundwater basins.

Water recycling is often termed a “drought-proof” supply, and state initiatives aim to be reusing about 2.5 million acre-feet annually within a decade.

How will climate change affect our water supply?

While scientists don’t know if California will see more or less precipitation in the future, average temperatures will increase. This will worsen water storage issues for a variety of reasons.

Warmer winters mean less precipitation will fall as snow and more as rain, which will quickly fill reservoirs and force managers to release water from dams. With less snowpack, flow to reservoirs could slow to a trickle between spring and fall.

Research also has shown that warming, by increasing evaporation, will cause a devastating 35% flow reduction this century in the Colorado River, one of Southern California’s key sources.

Rising sea level also threatens freshwater supplies. Seawater could eventually flood Delta pumping stations, spoiling the water supply of millions of people and seeping into coastal aquifers.

Will technology help?

It probably will. Consider desalination, which removes salt from seawater. It seems like something between a miracle and a no-brainer. But desalination is expensive, and only a few small plants have been built in California. It also can generate greenhouse gases and requires disposal of brine. As some skeptics have joked, desalination is a promising future technology — and it probably always will be.

Water recycling is more promising, and its technologies are advancing. State policies call for more sophisticated systems that purify reclaimed water to a drinkable state. Only a few such facilities exist in the world.

Capturing stormwater could be cheaper. Diverting runoff into treatment systems or storage basins could, according to one analysis, add as much as 630,000 acre-feet each year in coastal cities.

And if times get really hard, water might be harvested from fog by placing fine mesh screens on seaward bluffs and dunes. Stay tuned.

Wouldn’t it just be cheaper and easier to consume less water?

Yes. For all the high-tech ways to fortify and expand our supply, the easiest, cheapest and potentially most effective solution is to use less water to begin with.

The Pacific Institute, a think tank in Oakland, says that conservation could cut California’s water use in half.

In fact, conservation has already helped. In Southern California, total urban demand — residences, businesses, institutions and parks — exceeded 200 gallons per person per day in the early 1990s. In 2020 it was about 130 gallons per person per day. That means a population that has grown by several million people has reduced water use by more than a third.

Are farmers wasting water?

Some farmers use water inefficiently, but in general, they try to squeeze as much “crop per drop” as possible. Many growers have retired flood irrigation and wasteful sprinklers and adopted drip irrigation systems. They also use technology that autonomously monitors soil moisture and remotely opens and closes water valves.

Almond growers, for example, grow each nut with one-third less water than 20 years ago. However, because acreage has more than doubled, the industry still uses more water than it did.

How did former President Trump affect California’s water problems?

In 2019 the Trump administration introduced a plan that critics say weakens Endangered Species Act restrictions on pumping water from the Delta.

Many farmers welcomed the proposal since it could increase their annual water deliveries by half a million acre-feet or more. But environmentalists and fisheries biologists called it “an extinction plan” for winter-run Chinook salmon and Delta smelt. They say it will allow more diversions during key migration periods, increasing the odds the fish will be sucked into the pumps, and it may affect spawning salmon.

California and some environmental groups sued, and in May 2020 a judge blocked the plan from going into effect.

What’s the governor doing?

The Newsom administration created a “Water Resilience Portfolio” of more than 100 ideas. It focuses on four areas: diversifying water supplies, protecting the environment, improving storage and conveyance systems, and preparing for climate change and natural disasters. A Delta tunnel is a priority, as is a new Sacramento Valley reservoir.

The portfolio stresses the need for more underground storage, as well as desalination and farming programs that build healthy soils that retain more water. It also recommends identifying minimum flow rates to protect and restore salmon runs. It warns, too, of a future climate that will challenge existing storage systems.

Overall it’s a long to-do list. Jeffrey Mount of the Public Policy Institute of California said the portfolio was “a Herculean effort,” but it doesn’t mandate action, it just makes recommendations. “This is a plan to plan,” Mount said.