Although they are far from mortal enemies, there is a bit of a cat-and-mouse game going on between a reporter and an ex-president in Oakland author Carolina De Robertis’ fifth novel, “The President and the Frog” (Knopf, $24.95, 224 pages). Their exchange revolves around a backward look at the life of the aged, unnamed protagonist, a former revolutionary in a South American nation who underwent long years of torture and imprisonment before emerging to ascend to high office, becoming both beloved by his countrymen and revered around the globe for his humility, compassion and lifelong thirst for justice.

But as the interviewee faces his interlocutor, an admiring woman journalist from Norway, he is harboring a secret. What he wants to keep to himself is how, while deep in isolation and suffering unimaginable deprivation, he managed to hold on to his will to live. The key to his survival — if not, perhaps, his hold on sanity — turns out to have been his recurrent and frequently fractious conversations with a thoroughly obnoxious frog, an apparition (or was it?) that comes and goes at its own whim.

De Robertis, an American of Uruguayan heritage who immigrated to the United States from England at the age of 10, has dipped her pen into magical realism before, in novels such as “Perla” and “The Invisible Mountain.” But what she has accomplished with this compelling narrative, which is purposely set immediately after the 2016 U.S. election, is to produce a tale that is equal parts fable, political manifesto and utterly engaging testament to the resilience of the human spirit.

We, of course, had questions about how this unusual novel came about, and De Robertis most graciously provided answers.

There is a very early reference in your novel to “the disastrous recent election in North America.” Is this book a warning of sorts?

Carolina De Robertis: One of the things I love about novels is their capaciousness: Novels are vast; they can hold many threads and be many things at once. So certainly, this book can be read as an alarm bell for the times in which we’re living and the challenges we face as a society. But it could also be read as an exploration of what’s possible in terms of transformation, both personal and collective.

There is a whole tradition within Latin American literature known as the “dictator novels,” which began with Guatemalan Nobel laureate Miguel Ángel Asturias’ “The President” and continued through fiction by García Márquez, Vargas Llosa and more. Although those are powerful works in their investigation of authoritarian minds and social resistance, I see “The President and the Frog” as not just a tribute to that tradition, but also a subversion of it. We’re used to seeing the Latin American despot as the cautionary tale, but in this book, the Latin American leader is a progressive beacon of hope, and meanwhile, it’s 2016, and look at what’s just happened in North America. Authoritarianism doesn’t belong to just one hemisphere. Nor do corruption, social inequities, grief, love, loss, courage, hope or any of the other themes at hand.

You chose not to give your protagonist a name or a particular country. Why is that?

De Robertis: I’ve been writing novels set in Uruguay and neighboring Argentina for 20 years now, so I’m no stranger to creating detailed settings specific to a time and place. For example, my last novel before this one, “Cantoras,” chronicles the lives of five queer women during the Uruguayan dictatorship and its aftermath, and it felt important to bring that world to life with a wealth of historically accurate detail. For this book, however, I wanted to explore the possibilities of a different approach, in which an unnamed country allows for a greater freedom to explore the intimate truth. The country in this novel is based primarily on Uruguay, and the protagonist is inspired by former president José Mujica, but this is also a parallel fictional world with its own mysteries and wildness.

In choosing this aesthetic path, I’m grateful to draw on a long rich tradition of novels where an unnamed country is the setting for exploring big, bold themes — such as Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West,” José Saramago’s “Blindness,” Daniel Alarcón’s “At Night We Walk in Circles,” Hanan al-Shaykh’s “Women of Sand and Myrrh” and Saleem Haddad’s “Guapa.”

So why a frog, in particular, instead of, say, a turtle or an owl? And why was it important to make it a profane, rude frog?

De Robertis: It’s funny you ask this, because there is a turtle in my second novel, “Perla”! It doesn’t talk, though. The creature in this novel is a frog because the first spark of inspiration came from an actual interview with José Mujica, while he was president of Uruguay, in which he said that one way he survived brutal solitary confinement as a political prisoner, in the dictatorship years, was by talking to frogs. This image stayed with me and filled me with questions. What were those conversations, what could they have been like, and what might they convey about those secret crucibles in which we face ourselves and come through fire? So the character of the frog was originally born from a seed of fact, planted in the soil of imagination.

Also, frogs are amphibious creatures, belonging to two worlds at once, which means they inhabit a unique symbolic realm.

Can you tell us a little bit about the juxtaposition of the absurd and the horrific that we encounter so often in the novel? Are they meant to balance?

De Robertis: What an intriguing question! I think one of the things that’s difficult for us, as human beings, to absorb about horror is how it takes place alongside the ordinary. Trauma and beauty, humor and sorrow often exist within shared space. I’ve spent a lot of my adult life thinking about trauma, of both the personal and collective kind; in my 20s, I worked at a rape crisis center in the East Bay and listened to the stories of over a thousand sexual assault survivors. This experience shaped me, not only as a person and as an activist, but also as a writer. The question of how we survive trauma is inextricably linked with questions of how we heal, yes, but also questions about how we resist, how we live in the mundane world, how we create and re-create ourselves, how we laugh, how we flourish and how we break the walls that cage us. So the juxtaposition of these different moods and elements feels essential to an exploration of the whole.

You chose “Once upon a time” both as your opening sentence and as the entry point for several subsequent chapters. Why was such a conventional trope useful to the book’s purpose?

De Robertis: Aesthetic choices are at their most powerful when they’re made, not just for the heck of it, but in service of the work at hand. For this book, I wanted to tip this very political story with serious underpinnings into the realm of parable, of unfettered imagination and, yes, of fairy tale. It seemed essential to the spirit of the book, so why not signal that invitation to readers in the very first line? Come, take a flight, take a dive. To me, the title of the book sets the stage for that fairy-tale feel as well, playing on “The Princess and the Frog” — though with a gender-bending streak to it, because we’re not used to stories about women and girls being invoked when talking about male presidents, are we? What makes a story weighty and important? Who decides?

Your protagonist, as enlightened as he seems to be, struggles with the concept of homosexuality. Why was that important to include?

De Robertis: It was important to include this because it’s true to life and reflects one of the deepest challenges facing all our social movements, namely, the ability to connect one issue area to others. The movement the protagonist arose from focused on economic equity, but how can you have that without fully addressing homophobia? Or sexism? All of these movements are connected, because they connect in real people’s lives. It was true then, and it’s true today: For example, we’ll never overcome the climate crisis without dismantling white supremacy — just look at how, here in the U.S., the same right-wing politicians refusing to address the climate crisis are also leveraging racism to enact voter suppression and stay in power. Without intersectionality, there is no social justice and no future for the planet.

For me, as a queer Latina immigrant writer, I was interested in really exploring what that inner journey looks like for someone who’s committed to the idea of liberation, but who is straight and male and finds himself challenged to stretch his thinking about what liberation for everyone actually looks like. I wanted to delve into that experience with compassion, but also with an honest eye.

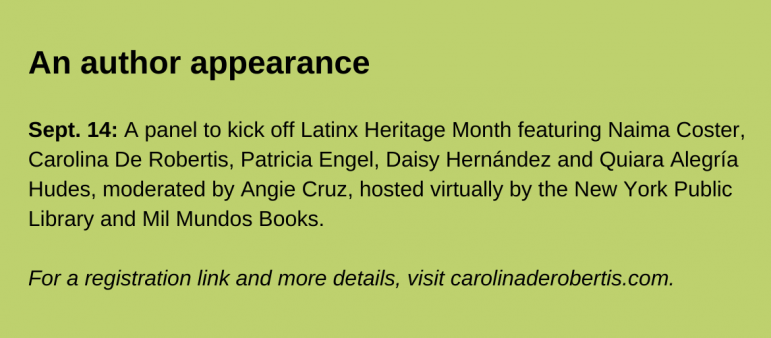

The cover art for Carolina De Robertis’ “The President and the Frog” (Photo courtesy Knopf)

Oakland author Carolina De Robertis has published five novels so far. (Photo courtesy Lori Eanes)

The first impression we come away with after meeting your ex-president in these pages is his deeply rooted humility. How much was our own ex-president in mind as you were crafting your fictional one?

De Robertis: I wrote this book during the Trump Era, and I was aware of writing with a double consciousness of both the place and time in which it’s set and the realities I was living. But the portrayal in this book isn’t ultimately about Trump. It’s about power, more broadly — how people hold it, how we wield it, how it shapes us and how we shape it in turn. We have lofty ideals about politicians as public servants; what does it mean when those ideals are corrupted? And what does it mean when somebody actually, sincerely attempts to carry them out? What do such attempts mean about the limits and possibilities of power, not only for presidents, but for the rest of us as well?

Can we assume that many of your ex-president’s thoughts are also the thoughts of Carolina De Robertis? (For instance: “It doesn’t take a military takeover for a government to menace its own people.”)

De Robertis: Certainly, there are places where the ex-president’s philosophy overlaps with mine, though there are also places where that’s not the case, such as his struggle to understand queerness. But I think the more important question is how readers experience the protagonist’s philosophy and ideas. As with any novel of ideas, the reader does not need to agree with the protagonist, but can take the text as an invitation to exchange; how do these ideas land with you, what do they stir in you, what do they spark? Even the ex-president himself is not always sure about his ideas. Even as he talks, inside, he’s often searching, questing, wondering; we get to see both the roots of his convictions and the inner vulnerability of grappling with big, thorny questions.

As for that particular quote, in light of the current circumstances in various regions of the U.S., I do believe it speaks for itself.

One thing you surely did NOT make up is the model of a just revolution begun in earnest commitment to the good of the people that unravels because of the strength of the opposition and the fragility of its would-be followers. Did you have a particular historic event in mind?

De Robertis: I had many historic events in mind. I modeled the revolutionary movement in this book on Uruguayan history, which I’d been researching for 18 years for other novels. I also drew on movements in other Latin American countries. However, I really aimed for this narrative to explore deeper, broader questions about social change and how we enact it that have everything to do with who we are today in the U.S. and beyond and the future many of us would like to see for our communities. I’ve been an activist for at least 25 years, and I know that, in caring about the gap between the world as it is and the world as we’d wish it to be, I am far from alone. How do we create meaningful social change in the face of deeply entrenched injustice? How do we address the internal as well as external barriers to that change? What’s the best use of our energies as people who care deeply about human life and our planet? What would it look like — really look like — to create a world where everyone can be safe and free?

These questions are perennial. They don’t just belong to a single setting. In this book, I drew on one particular context — Latin American revolutionary movements — to shape a narrative that I hope will offer resonance beyond its place and time.

Sometimes your frog sounds like a Buddhist (“There is One. In the One is All.”) But he seems to be a multipurpose critter: provocateur, crutch, guru, therapist — am I misconstruing or leaving anything out? Did he seem real to you?

De Robertis: Yes, the frog is absolutely real to me, as a discrete character whose personality and inner life are unlike anyone else’s. Like many fictional characters, he is a blend of many ingredients, from the real to the imagined. I knew the journey he and the president took would be psychologically and spiritually profound — that there would be a strong dramatic arc between them — so, to develop him, I in part drew on sacred sources, such as the “Bhagavad Gita,” a Sanskrit holy text driven by a conversation between the human Arjuna and the divine Krishna, about how to live and which I’ve been reading in various translations for years. I did look to Buddhism, including the “Dhammapada,” and, also, to wisdom stories about trickster deities whose needling catalyzes awakening — particularly those of Eleggua, of the Orisha tradition rooted in Yoruba culture and present in many Afro-Latinx and Latin American communities. I did not copy from these sources, but they have been wells of deep listening and learning for me. With these and many other tools, I shaped the character of the frog.

Might your frog and your Norwegian journalist have anything in common besides both prodding the protagonist to plumb his past?

De Robertis: Another interesting question. What strikes me here is that the Norwegian journalist and the frog are two characters who never actually meet in the course of the book, as they exist in separate narrative strands. And yet, they interact inside the protagonist’s consciousness. That’s something that’s so compelling to me about fiction: the way it can lay bare the secret connections between people, between moments, in ways that mirror the delicate webbing of our own lives.

Are we as readers free to regard the frog as a figment of the prisoner’s fevered imagination? Do you care one way or the other?

De Robertis: I think readers have the right to experience books in their own unique ways, and some of the novels I’ve loved most have yielded a multiplicity of interpretations. So I embrace the notion that there’s room for readers to make meaning from this narrative in different ways. Is the frog real? What is reality? Where is the line between our inner world and other realms? Fiction doesn’t have to be about finding tidy answers to our questions; instead, it can be a dive into the questions themselves.

Last question, also about a creature as a character: Your protagonist has a beloved and devoted little dog named Angelita who, because of his carelessness, only has three legs. Do I detect a hobbling metaphor at work here?

De Robertis: I’m delighted that you brought up Angelita, because she happens to be a character based on real life: José Mujica, while president of Uruguay, had a dog with a similar story and temperament. Sometimes, as writers, in blending a real fact into our fiction, we come to see it in new ways. As I wrote, the story of Angelita’s wounding, and of her tenderness as an animal friend, lent new resonance to the themes of healing, pain, love and renewal that were already in the novel and that run through the hidden heart of the novel, at least to me. There is infinite pain in our world — there’s no question — but one of the things I wanted to lift up in this book is the infinite possibilities that also exist for renewal, healing and love. How do we best harness those qualities in our lives? That may be the question that most deeply fuels this book.