If there’s a silver lining to being young and bedbound, it’s the doses of reassurance and happiness that University of California, San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospitals heap on their patients.

Ask Laura Rapp.

The Clovis resident’s 11-year-old son, Mason, has cerebral palsy and underwent surgery in late April to reduce the spasticity of his muscles.

During the six weeks he was hospitalized at Benioff’s Oakland site, Rapp was surprised and delighted to discover that Mason’s treatment plan included a music therapist, who brought him joy in the form of a portable electronic drum set.

“He would rock out in his wheelchair,” she laughed.

Mason Rapp underwent surgery in April.

As part of his treatment plan, the 11 year old had music therapy sessions where he rocked out with percussion instruments.

(Photos courtesy of Laura Rapp)

“It was 10 times better than (watching) music videos on YouTube,” Rapp said.

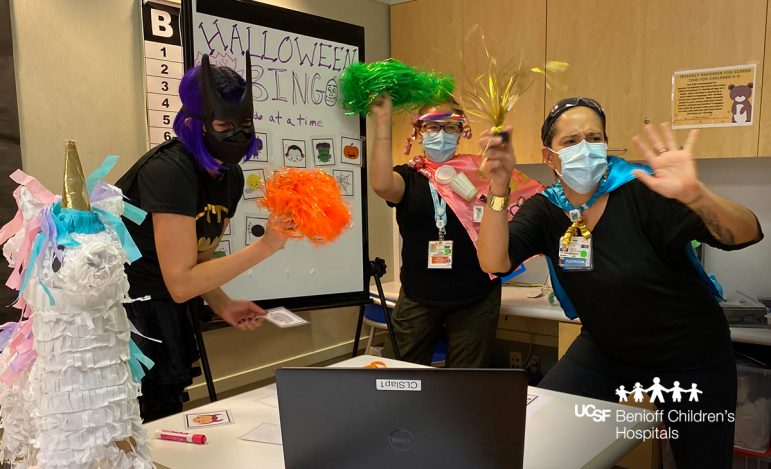

Every one of the patients at the Oakland and San Francisco campuses, from newborns to 21-year-olds, receives care that goes well beyond healing the body.

“I always say that our team is responsible for upholding the emotional safety of patients,” said Divna Wheelwright, who oversees this holistic approach as manager of the Child Life Services at the Oakland campus, as well as at specialty clinics in Walnut Creek.

Benioff Children’s Hospitals’ acute care facilities have done away with the outdated model of medical care that has clinicians focusing solely on the illness to the exclusion of a patient’s other needs — now they treat the whole person, Wheelwright said.

Dispensing the wide variety of creative and customized care are Child Life specialists who assume the role of teacher, social worker, recreation director and guardian angel as they use art, music and a host of other activities to reduce youngsters’ stress.

There’s even a dog in the mix: Trinity the Golden Labrador has been encouraging and comforting children during their rehabilitation sessions for the past seven years, when she became Benioff Children’s Hospital (BCH) Oakland’s first canine companion.

The Oakland hospital, which has been providing these services since 1980, brightened the lives of children and teens over the course of roughly 80,000 in- and outpatient visits in 2020; youngsters accounting for about 40,000 visits have circulated through Child Life Services’ 223 beds so far this year.

And although insurance doesn’t cover this extra layer of care, families don’t pay a dime. The hospital instead relies heavily on donations, which makes it difficult to expand the offerings with limited staff, and is why patients usually must have a doctor or nurse refer them to the program, Wheelwright said.

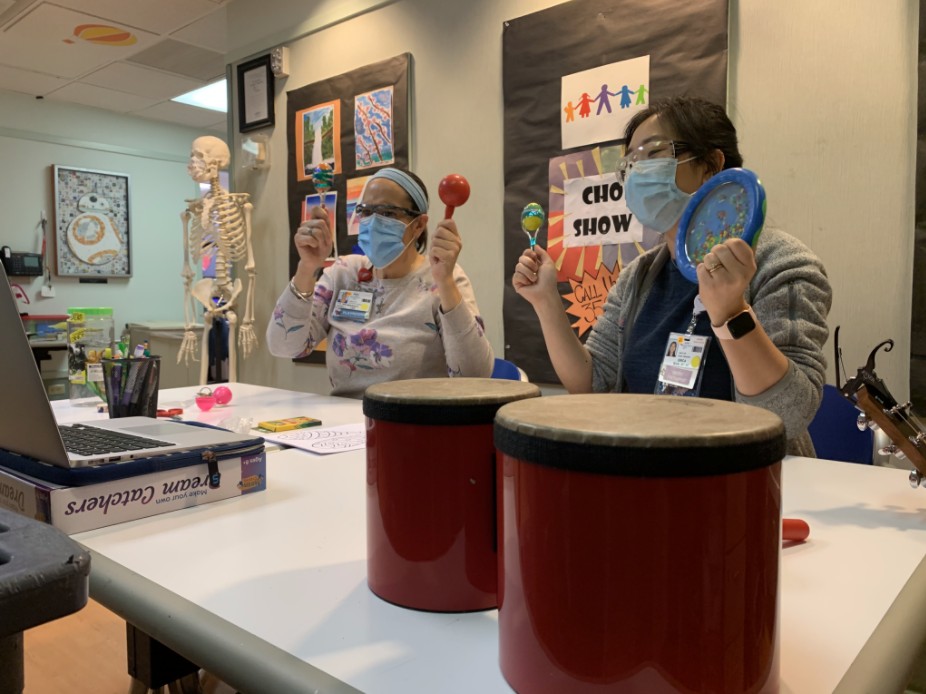

A visitor might find music therapist Lauren Ragan easing the apprehensions of cancer and sickle cell anemia patients by strumming on a ukulele or serenading them on the piano.

Alternatively, she’ll hand youngsters percussion instruments and let them rattle and thump to their heart’s content.

Ragan recalls the 6-year-old oncology patient she recently tended to who had never been admitted to a hospital before and was anxious.

With maracas and small drums, the girl began singing about her fear of the unfamiliar surroundings by projecting the emotion on her stuffed animals while Ragan accompanied her on guitar. But the child also expressed assurance that her toy elephant, although sad, was taking its medicine and would recover.

The exercise gave the child an outlet for expressing her feelings and, by learning to do it on her own, she reclaimed a measure of autonomy over her circumstances and was able to calm down, Ragan explained.

“That’s what we as humans need — we need to feel safe … to have a sense of control,” she said.

A person’s mental and emotional health affects his or her physical well-being, added Ragan, one of three music therapists at BCH Oakland.

“If a child is scared, their medical treatment is not going to be optimal,” she said.

Fear amplifies pain as does focusing on it. Conversely, distractions can interrupt neural messages to the brain. That’s why when doctors can’t safely administer more pain medication, music can provide a positive distraction, Ragan said.

She chooses the music she plays according to patients’ preferences to increase the chance their bodies will respond to the stimulus; depending on the genre they grew up with, selections might include hip-hop or regional Mexican music known as banda.

And while teens enjoy karaoke or record original songs on professional-caliber equipment in a lounge that doubles as a music studio, a therapist over at San Francisco’s Mission Bay facility might be using music as a reward to help infants born before they developed the sucking reflex.

A Child Life music therapist plays for an audience of one in BCH Oakland’s NICU.

(Photos courtesy of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals)

A speaker that’s connected to a pacifier is activated when the newborns suck correctly, playing a lullaby or even the soothing sound of a parent’s voice.

“Babies respond to the sounds of their mother more than anything,” Ragan said.

Because music stimulates the entire brain, it can also help the child who’s suffered a head injury and must learn to walk again by reestablishing neural connections, she said.

Benioff Children’s Hospitals’ Child Life specialists are adept at using play to their advantage, whether as a conversation opener to learn what a youngster is thinking, to educate patients or to help them relax.

Staff members might give a LEGO ambulance set to a child who shows up in the emergency room because by watching how he or she plays with the toy they can better understand how that youngster perceives the experience, Wheelright said.

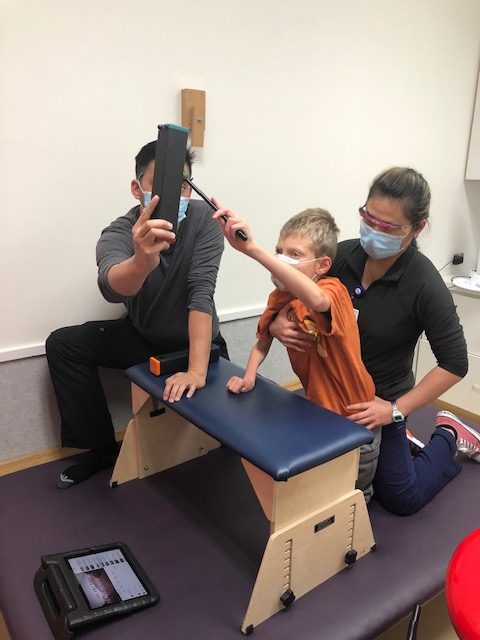

Play, like music, can also make procedures a little less uncomfortable.

ER patients can all but count on getting a needle for an IV or blood test, said Child Life specialist Rose Tandeta, adding that nasal swabs for COVID-19 are currently another standard protocol.

“A lot of kids say that the (virus) test is worse than the IV placement,” she said, noting that it makes eyes water and feels like a sharp pinch.

There’s also soreness from pulling off the tape keeping bandages in place and inserting nasogastric tubes to feed and medicate a patient, both procedures that are done while patients are awake.

Play is the language of young children, said Child Life specialist Hania Thomas-Adams, noting that they typically rely less on words to communicate.

As such, it’s often the best way of explaining what will happen to them and why; it also gives children the chance to voice worries or questions, and their caretakers the opportunity to correct any “wildly imaginative misconceptions,” she said.

Child Life specialists first might give children a doll and let them apply an actual tourniquet, swab the target area with alcohol, and then administer the needle themselves.

As a result, they are less apt to get upset when it’s their turn to be poked, Wheelright said.

Thomas-Adams also has helped children overcome the intimidation factor of anesthesia masks by using a stuffed toy to demonstrate how the gas would make them fall asleep. She kept the lesson fun by letting the child pick out a scented oil from her collection, which she then dabbed onto the inside of the mask for them to smell. Kids who returned for additional surgery years later still fondly remembered those sensory experiences, she said.

Like music, play is an effective distraction from whatever’s hurting.

Tandeta will help a patient relax with the guessing game “I spy,” using toys that light up and play music, or by watching YouTube together on an iPad.

The Child Life specialist also used guided imagery to take a 6-year-old boy’s mind off dressings that needed changing by having him close his eyes and imagine smelling funnel cakes as he walked into Disneyland with her.

Kids who must be isolated from others still can find pleasure in being able to play. Thomas-Adams once devised a creative way to accommodate a girl who loved beading and also wanted her company. She had a nurse give the youngster a string long enough to stretch from the hospital bed to the door so the two of them could do the crafts project together while maintaining a safe distance.

She also has entertained patients remotely, using Zoom to stage a puppet show. One boy was so enamored with her online poetry writing session that he insisted on continuing the fun from a gurney while staffers wheeled him to the operating room.

And the power of play made all the difference to a 4-year-old girl who had been in an accident that impaired her ability to walk. The child was frightened when she arrived, so Tandeta gave her Band-Aids and bandages to put on her dolls.

The girl plastered them all over the toys, and when she returned for additional surgeries “she wasn’t fearful of coming back,” Tandeta said. “She looked forward to playing with me again.”