In hard-hit Napa Valley, which has burned multiple times this last decade, successful winemakers and longtime residents are weighing their options to rebuild or move out entirely simply by looking at their property insurance policies

“They just can’t get insurance,” said Democratic state Sen. Bill Dodd, whose district spans the region’s celebrated vineyards. “Or the insurance is so expensive that there is no way they could ever afford that kind of coverage.”

Such a refrain is eerily familiar throughout Santa Rosa, Paradise, Ventura and other communities that have been ravaged by recent wildfires. As if a second dry winter and historic heat wave were just the opening acts, California homeowners are girding themselves for another destructive fire season that could raise their wildfire insurance rates to unaffordable levels.

The problem is catching. California’s streak of infernos has already created record liability for insurers: Insurance companies lost a total of $20 billion in 2017 and 2018, twice the industry’s profits since 1991, according to a white paper by Milliman, a financial consulting firm.

Insurers are betting climate change isn’t going away and that’s why they’re now pushing the state to allow them to factor in future flooding, mudslides and forest fires into customer premiums. If they don’t get their way, they say they’re just going to continue to drop more homeowners from coverage in a state where one out of three homes have been built in or near dense vegetation.

Who pays for wildfire costs?

That tees up a contentious debate in the Legislature over who should be responsible for the costs caused by natural disasters to homes built in the wildland-urban interface — homeowners, insurance companies or government entities that allowed them to build in the first place. Others argue that construction should be banned entirely in fire-prone areas in spite of a statewide housing shortage.

“There are no villains here,” said Rex Frazier, president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, which represents State Farm, Liberty Mutual, Farmers and other major insurers. “We are dealing with the way we used to do things, which doesn’t fit with our new reality. So that’s what’s causing the market to be out of whack.”

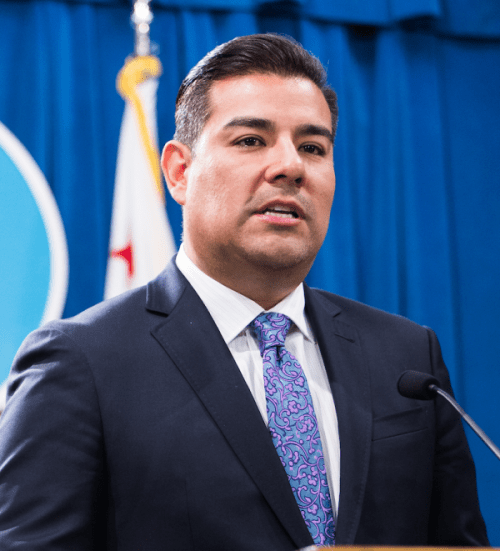

Draft recommendations from the Climate Insurance Working Group, established to advise state Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara, suggest allowing a contentious move to let insurance companies adjust premiums based on projections from natural catastrophe models. The shift, they say, will more adequately allow insurance companies to charge rates based on extreme fire risk. Supporters believe it could discourage building and rebuilding in high-fire zones. If adopted, it would be a dramatic change from the current structure, which is determined by historic rates.

So far, lawmakers appear receptive but Gov. Gavin Newsom hasn’t tipped the scales. “The administration strongly supports land use planning requirements and building codes to bolster wildfire resilience in our communities,” said Gopika Mavalankar of the governor’s office.

The insurance commissioner’s office declined to comment until the final report is released in a few weeks.

A catastrophe model

Insurance companies argue the move is necessary to keep private insurers in the marketplace. They point out earthquake insurance is already allowed to factor in future risk. California allows insurers to use market-based models to project premiums for earthquakes, but those models are owned and created by third-party businesses that don’t divulge their reasoning, citing proprietary information.

To others, though, the recommendation to allow insurance companies to use new models is worrisome.

Consumer Watchdog, a taxpayer advocacy group, argues that moving to a catastrophe model would not only increase insurance rates, but also eliminate transparency for how those rates were calculated.

Hard to get insured

For fire survivors like Patrick McCallum, whose home burned down in the 2017 Tubbs Fire, there’s suspicion that insurance companies could potentially manipulate data to increase premiums on homeowners.

“It’s an extremely difficult process to go through and complicated, and, I felt, not fair,” said the Santa Rosa resident. “They are profit-making companies. Still, with all of these disasters, (they) are still making profits.”

Due to cost and coverage, McCallum and his wife ultimately decided against rebuilding. They moved to another neighborhood within the city. Even so, they had difficulty getting homeowners insurance because of their past claim. McCallum said they got coverage on the 10th company they tried.

The working group’s recommendations also suggested that insurance rates could be used to disincentivize new building in fire-prone areas, adding that new development should be actively discouraged to limit state spending on infrastructure there. The arguments come at a precarious time for California as the state heads into fire season with an ongoing housing crisis. In 2020, California experienced five of the six largest wildfires in recorded history and nearly 11.2 million people live in the state’s wildland-urban interface.

Conversation for lawmakers

Carmen Balber, executive director of Consumer Watchdog, argues that insurance shouldn’t be used as the stick to keep residents from building in fire zones when government policies otherwise allow it.

“We need a conversation about incentivizing rebuilding in a place that burned down three times, but the insurance industry should not be making that decision based on its own private profit motive,” Balber said. “That’s a conversation for the government…It should not be the insurance industry’s job to decide where we build our homes.”

She adds it’s unfair to place the burden of paying for increased wildfires solely on residents who live near fire lines.

“We’ve told people they can build in the (booneys) and wilderness for decades and only now is it catching up to us,” Barber said. “It most definitely falls to the state to invest more seriously in mitigating climate risk—no individual homeowner is responsible for fire increases. But we shouldn’t be encouraging people to build in fire-risk areas. The problem is a political struggle.”

More houses, more fires

A recent study released by researchers at the UC Berkeley Center for Community Innovation and think tank Next 10 found that state and local land use policies and a statewide push to build more housing is increasing the economic and human cost of wildfires by pushing more building into high-risk fire areas. The report argues that state and local policies are primarily responsible for emphasizing rebuilding and retrofitting homes in high-fire areas, rather than offering incentives for homeowners to relocate after fires.

“We should be making this harder and we are not,” said Rob Olshansky, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an author of the study. “Just having people in the wildfire areas increases the chance of fire igniting. The main cause of fires is people doing stuff like using barbecues and spark plugs.”

The study also found that strict building codes and design standards for new homes across the state have propelled increased building in the open spaces on fire lines — rather than infilling in existing towns and city centers.

Lawmakers open to factoring in future risk

Lawmakers who represent communities devastated by fires are receptive to the idea of raising rates some — if it means their residents can continue to stay on their property.

Assemblymember James Gallagher, a Republican whose district includes Paradise, said his constituents’ biggest concern is access to coverage. They want to avoid the California FAIR Plan, which is the state’s insurer of last resort that comes with a hefty premium and only covers fire damage. Critics add that the plan was never created to be a permanent solution for California homeowners seeking fire insurance.

“I think that most of my constituents acknowledge that they live in high-risk areas and we are willing to pay,” Gallagher said. “But it has to be a reasonable premium, and I don’t think the government is going to be able to provide that on its own. You need the private insurance market to be part of that solution.”

The Yuba City lawmaker disagreed that the government should take responsibility for telling people where they can and cannot build. He said the state failed residents by allowing a backlog of tree clearing and thinning to accumulate.

Dodd said he supports allowing private insurers to factor in future disasters if it means residents in his districts can avoid exorbitant pricing offered by the FAIR plan.

“So many people right now are going naked with no insurance or paying seven or eight times the annual premium they did before,” the senator said. “If they raised the rates 50 percent, that would be a blessing.”