How do you hold queer history in your hands? What can you hang from a ceiling or pin to a wall that truly captures the full spectrum of a community of people so used to alienation, subterfuge and rejection of their identities, let alone their artistic prowess? In San Francisco, to ignore queer history is to erase entire pillars of society and the legacies — of embracing and celebrating gender fluidity, enduring through the AIDS epidemic and promoting medical marijuana — that they left those of us who remain.

Tucked within a housing complex at Haight and Laguna streets in San Francisco, the Haight Street Art Center is hosting one of its first shows since pandemic restrictions relented, “Queer Visions,” through Aug. 15 to pay homage to those who came before and helped guide the current community into the present. As the center’s executive director Kelly Harris says, it takes a hard look “into where you come from, to know where you’re going.”

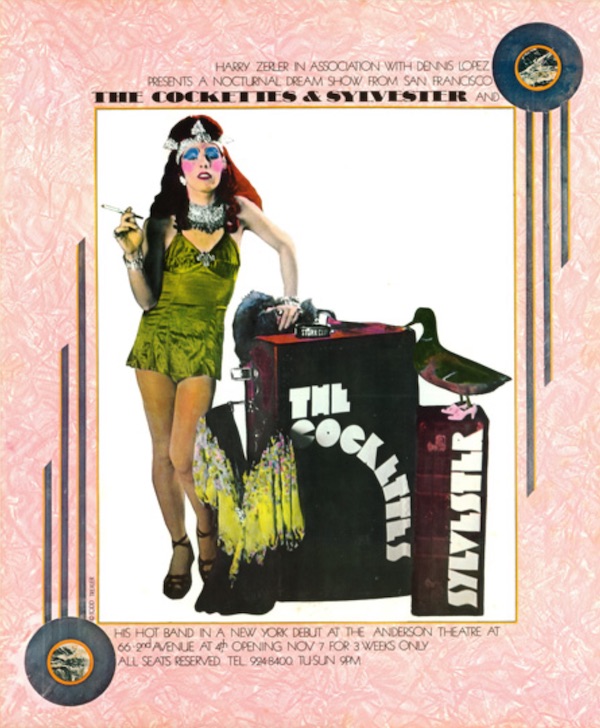

The admission-free show is a tribute, a two-story counterculture love letter really, to all the ways the vast, intersectional queer community here has gathered to claim space and cultivate joy against the grain of societal expectation. The front hallway is lined with posters by late gay artist Todd Trexler, who veered from the psychedelic, Grateful Dead roots of the art form to make memorable, one-of-a-kind posters for salacious midnight movies and drag queens like Divine herself.

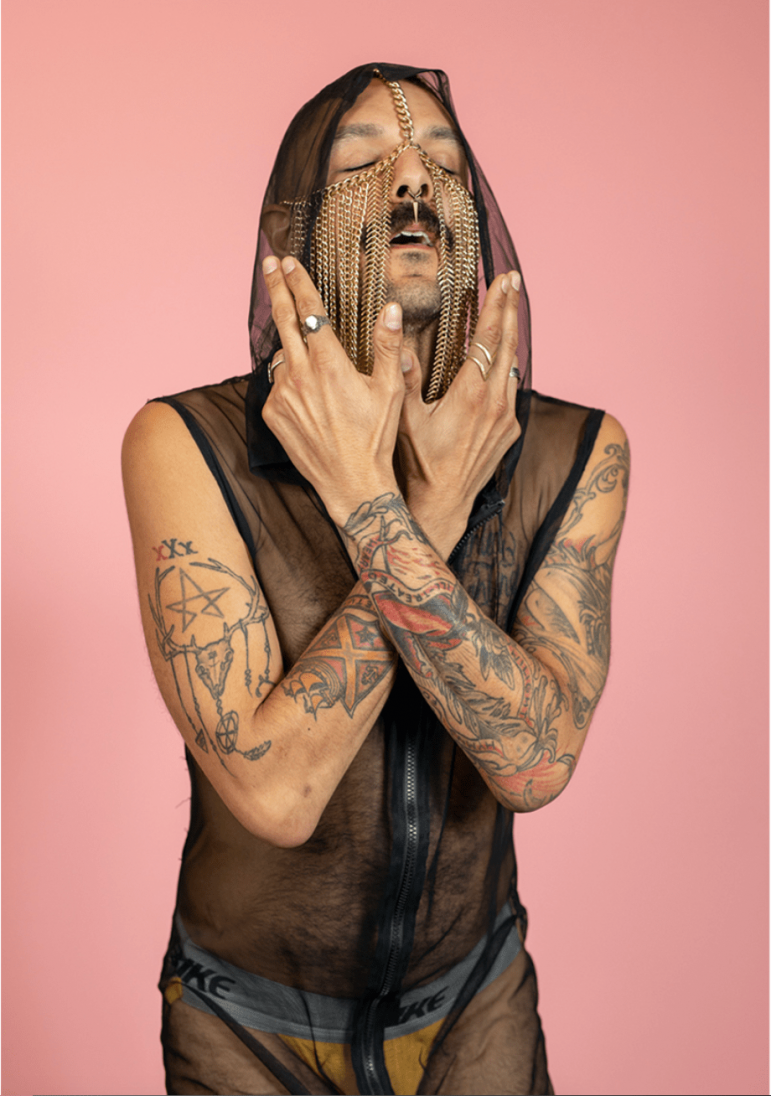

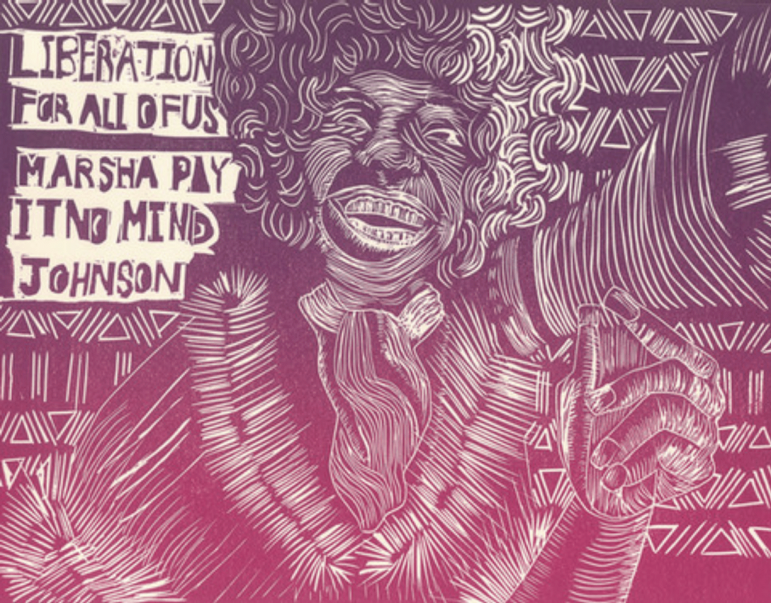

There are multiple rooms dedicated to San Francisco’s incomparable Stud bar, where all genders and orientations have been welcome since 1966. The staircases are lined with queer portraits, leading to a top floor full of print art made in tribute to queer elders and the ingenuity of generations who passed well before their time, due to incurable illness or bigotry.

“How do you honor the legacy of people who came before you? It’s so important for young folks to be with those stories and hear from people who are older than you, who have experienced something, especially when in a historically marginalized community,” Harris says. “Sometimes I worry the community can disconnect so quickly, because of generational misunderstanding.”

Harris was a rock musician (a member of the all-girl San Francisco electro soul-punk group Von Iva) and worked in nonprofits before joining the Haight Street Art Center, a universe in her own words that, should you come out unscathed, can prepare you for anything. While she joined the HSAC during the pandemic, the center has been open for around four years, specializing in the oft-overlooked mediums of psychedelic and poster art that the Haight neighborhood is known for to this day.

She identifies as queer, and took the reigns to execute “Queer Visions” after launching the center’s reopening show with local artist Jeremy Fish. Apparently, and unsurprisingly, there’s a lot of overlap between the posters made for Santana shows and the works of Trexler, whose poster work in the 1970s included popular bands but paid special attention to drag performers, funk musicians and movie showings unsuitable for a matinee. His posters, all drawn or collaged by hand, advertise distinctly queer experiences for queer audiences; the average (straight) Joe might not have been local drag troupe The Cockettes’ target audience, but evidently people were going.

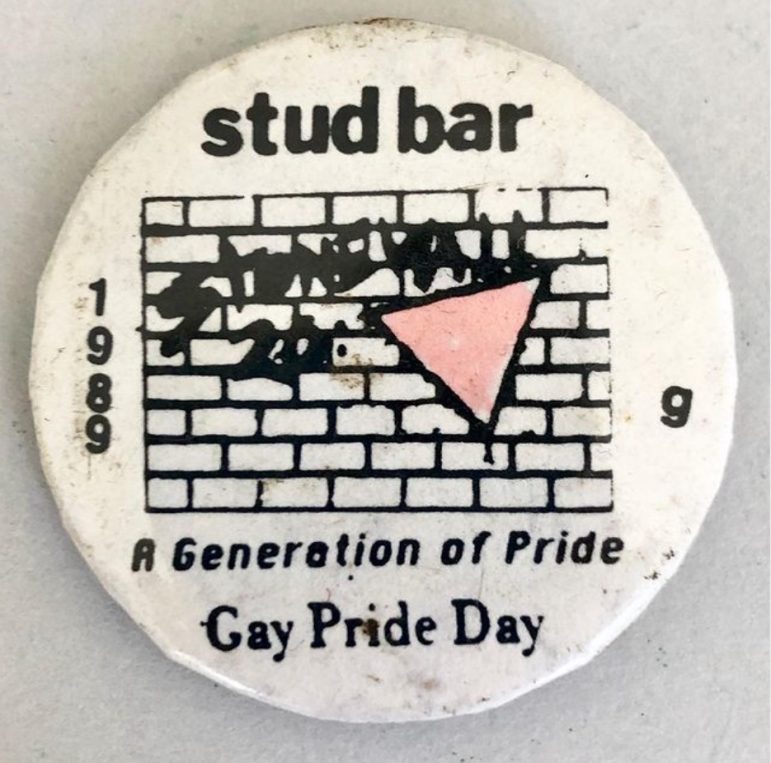

The posters adorn the hallway that leads to the shrine of The Stud, a multimedia exhibition for anyone to celebrate themselves as they have at the Stud bar for the last 55 or so years. The exhibition contains posters, hand-painted signs, leather chaps, an altar and countless photos of former Stud employees and patrons. The star, or stars rather, is the wall of Stud-themed pinbacks, an assortment of buttons celebrating different holidays, sporting events, party nights and loyalty. Since quarantine began, Stud employee Chloe Miller has been amassing these slippery little pieces of the past in a collection formally known as the Stud Pin Archives.

“It gives us a map of what was before and what is still here. It’s not only showing the pinbacks; there’s also this history for people who haven’t come out yet,” Miller says. “There’s still young trans people being killed, feeling it’s not normal. This is why I want this on [Instagram] because how can I directly communicate with everybody in the palm of their hand? It’s about accessibility.”

Miller has worked at The Stud for a couple years and been a patron for longer, but she hadn’t given any thought to archiving anything until the pandemic hit and The Stud, which had been restructured into a cooperative in 2017, closed.

Most of the pinbacks are the work of a former Stud bartender, Paul “Gidget” Sinclair, who began making them in the 1970s and continued to do so until his passing from AIDS in the late 1990s. They span all the holidays the American calendar celebrates and some they don’t, like the Polka Dot Prom, an annual party to give patrons a carefree, queer prom that they likely couldn’t have in high school.

Because the city is the size of a pinhead, Harris already knew multimedia artist Lauren Tabak, whose portrait series “Gayface” and collection of portraits from The Lexington — San Francisco’s last lesbian bar, which closed in 2015 — adorn some of the center’s walls. And Tabak, as luck would have it, knew Miller.

After more than a year bunkered down, the Stud Collective is currently on the prowl for its next home base. Miller has been developing its merchandise, which includes shirts, sweatshirts, pins and a tote bag. The collective has a Patreon, a podcast and a GoFundMe for those who want to pledge support.

On the way to the second floor of Haight Street Art Center are rooms with additional artwork by printmaker Katie Gilmartin, who also directed the “Queer Ancestors Project” upstairs, which asks young queer artists to consider and render whom they see as their queer ancestors and the space between them. Gilmartin also has a series of imagined pulp paperback covers inspired by the city, giving the bay fog a sinister sentience and putting young women in precarious poses. The vibrant prints of Amir Khadar, created for Forward Together and the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, convey the love to be found in queer chosen families, especially for queer, BIPOC immigrants.

On the wall at the head of the “Queer Ancestors Project” is a flyer advertising a bundle of products that, admittedly, can be conducive to creative expression: cannabis. Thanks to another connection on the pinhead that is San Francisco, the Haight Street Art Center has also partnered with local delivery service Sava to curate a gift basket full of queer-owned cannabis brands as a fundraising endeavor.

Sava’s cofounder Andrea Brooks, who identifies as a lesbian, has been using cannabis for years to treat the repercussions of what she calls a life-changing injury. She was told she could be permanently disabled and spent a couple years taking her prescribed pain medications. When she reconnected with a friend who grew cannabis, she was able to wean off opioids and onto a medicinal, cannabis-based regime that works for her.

“Cannabis was not something I thought of as something that would help me,” she says, but smoking is believing. “I wasn’t healed overnight. But I could do the things needed to be brought back to health.”

She founded Sava, which is women-owned and led, Latinx-owned and queer-owned, as a thoughtful, well-curated and education-rich shopping platform for consumers who were overwhelmed, and underwhelmed, by the traditional dispensary experience.

Brooks and Harris had common ties and, as they found out, common goals. Cannabis companies have had a reckoning of their own this past year — as cannabis was deemed an essential business during the pandemic — over the industry’s lack of activism for justice reform and philanthropy in the face of a public health crisis. More and more companies are platforming causes and making donations, but fewer are attributing the multibillion-dollar industry to the local queer community.

The city’s reputation for both queer and cannabis rights isn’t by coincidence: The first openly gay San Francisco supervisor, Harvey Milk, helped get one of the first cannabis decriminalization propositions on the city ballot before he was assassinated in 1978. It was Milk supporter Dennis Peron, an openly gay Vietnam veteran and longtime political activist who opened the first cannabis dispensary in the city back in the mid-1990s. Peron’s friend and fellow activist “Brownie Mary” Rathbun had begun distributing pot brownies to gay men suffering from “wasting syndrome” caused by AIDS and to cancer patients free of charge in the 1980s. Peron also co-wrote Proposition 215, the definitive state legislation that legalized medical marijuana in California in 1996.

“It’s really impactful, to keep history alive and community together,” Brooks says. “Cannabis [history] is rooted in queer history, and [that] needs to be remembered constantly. In the queer community, it’s important that Dennis Peron’s name is still mentioned, [along with] Brownie Mary, Harvey Milk. The histories are tied.”

Thankfully, there’s an array of benches at Haight Street Art Center, plenty of seating for when the art overwhelms. And it will, as you gaze at the smiling faces of a generation stolen by the AIDS epidemic, a trauma that the youth have been largely spared from, even as they face uncertainty about what comes next, especially as the most recent global pandemic continues to develop. But the future is less daunting with a map of the past, and anyone who’s set foot in this city could benefit from the compass in “Queer Visions.”

“The people who have ridden out the storm, who have lived through many cycles of shifting, we’re trying our best to hold on to those stories,” Harris says. “You know when you’re in a group of people who want to share legacy and history.”

* The free “Queer Visions” exhibition runs through Aug. 15 at Haight Street Art Center, 215 Haight St., San Francisco. The center is open noon-8 p.m. Thursdays, noon-6 p.m. Fridays-Sundays. Learn more at https://haightstreetart.org/blogs/news/queervisions.