Finally, after a delay of some 14 months, museum-goers now have the chance to see a major retrospective of the quilts of the late Richmond artist Rosie Lee Tompkins, on display in all their glory at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

The comprehensive “Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective,” which was very briefly open in 2020 before the pandemic shuttered BAMPFA and other museums, includes 64 works — many of them never before displayed — spanning several decades of work by one of the foremost contemporary textile artists.

This exhibition — curated by Lawrence Rinder and Elaine Y. Yau — was largely made possible by the 2018 gift to the museum of the entire 3,000-work collection of African American quilts amassed by Oakland psychologist, Eli Leon, a longtime collector and scholar of the art form.

Leon’s collection includes the majority of Tompkins’ work, some 500 quilts, as well as works by more than 400 other quilt artists, which BAMPFA intends to make the subject of a major 2023 exhibition.

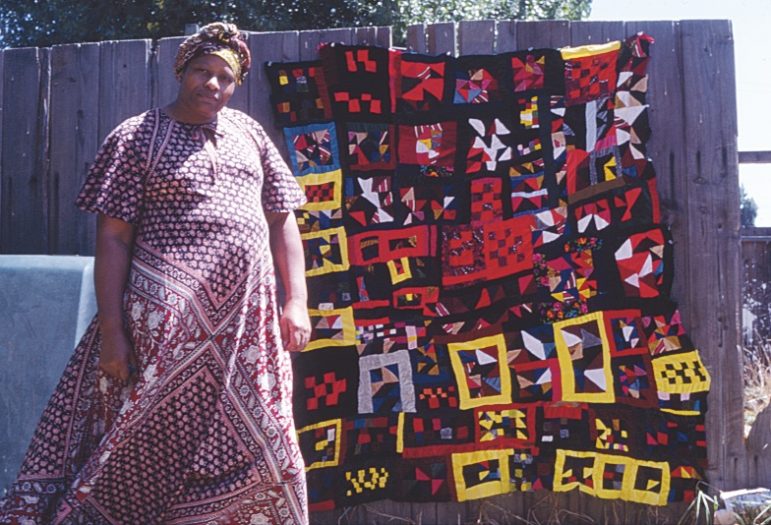

Tompkins was born Effie Mae Martin in 1936 in Arkansas, where she learned quilting from her mother as a child. She didn’t start quilting regularly until she was an adult, a nurse living in the Bay Area city of Richmond who married and divorced a man named Ellis Howard and was raising five children and stepchildren. To protect her privacy, she and Leon, who met her at a flea market and became her biggest patron and fiercest advocate, came up with the pseudonym Rosie Lee Tompkins in 1980.

For those who think of quilts exclusively as consisting of patterns of recurring design, scale and color, the pieces in the current show will come as an enormous surprise.

Tompkins’ works are improvisational in the tradition of African American quilt making. They display not only the individual aesthetic decisions of the artist but also are personally revelatory and reflective of her belief that her artistic skills were a God-given gift.

Though Tompkins is often described as a quiltmaker, Tompkins’ works are more accurately referred to as pieced tops, not quilts. While a number of those on display are finished quilts, it was not Tompkins who did the finishing steps of attaching the pieced top to a second piece of fabric through decorative stitching, often with a layer of filler between the top and bottom fabrics.

For that, Tompkins employed other quiltmakers. Her interest was overwhelmingly in the combination of colors, designs and found objects that make these pieced tops so remarkable, be they quilts, pillow covers or wall hangings.

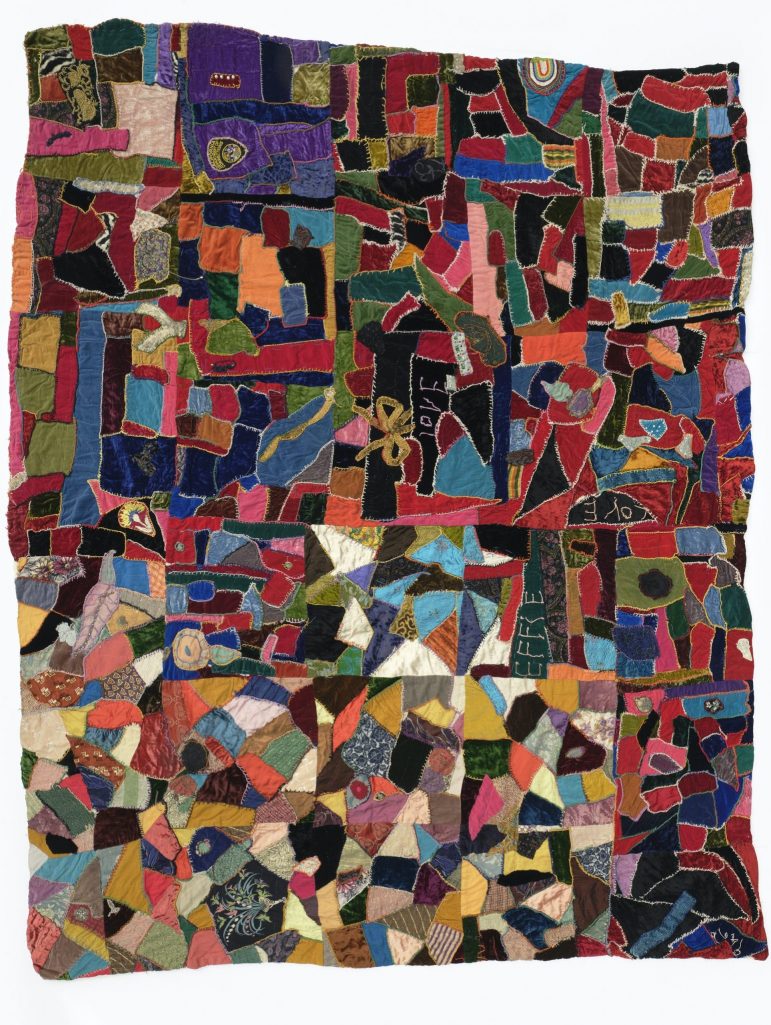

In her early works, Tompkins used a broad range of colors and fabrics. Some are restricted to a limited palette; others revel in their variety of texture and pattern. They are often arranged in a seemingly random way, but create a dynamic, vibrant effect. The individual pieces she used in her quilts are hand-cut and not uniform, but the work as a whole has a dynamism and visual completeness that incorporates its disparate parts.

This untitled 1996 pieced top by Tompkins, quilted by Irene Bankhead, puts together a wide range of colors and shapes for a vibrant, dynamic effect. (Photo courtesy BAMPFA)

Circle patterns called “yo-yos” are featured in Tompkins’ 1999 piece “Thirty-six Nine-patch, Three Sixes combination,” quilted by Irene Bankhead in 2007. (Photo courtesy BAMPFA)

A later quilt from 1996 expands the use of found images, incorporating found T-shirts with images of Michael Jordan, O.J. Simpson and Magic Johnson, as well as Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X and others. They appear under the printed words, “Strong Men, Keep on Coming.” Embroidered on the black and white surface of the quilt top are citations of biblical passages, appliquéd crosses and “Effie,” Tompkins’s birth name, as well as her date of birth.

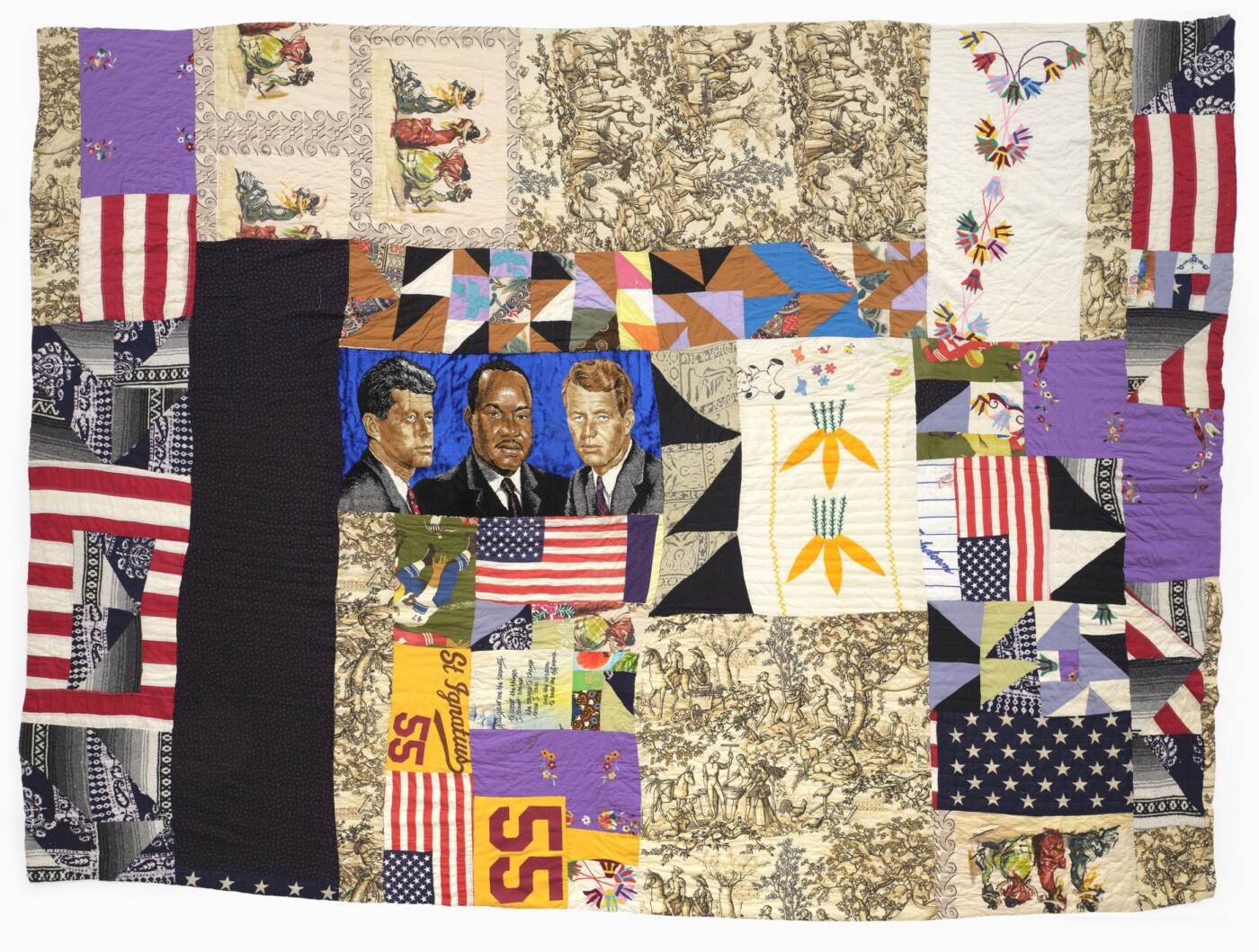

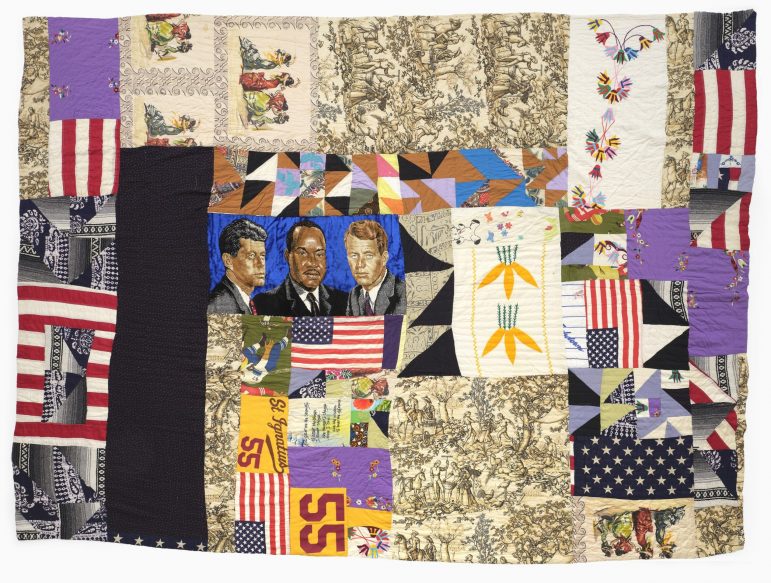

In another work from 1996, Tompkins joined a found dish towel portraying dancing figures with a manufactured religious tapestry, fragments of the American flag in blocks of stripes and half-squares of stars, and images of dogs, cats and chickens to create a patchwork that demands close attention.

In the decade before her death in 2006, Tompkins generally worked on a smaller scale —abandoning any relation to a functional quilt — and with a much reduced palette.

One particularly arresting piece is entirely in black and white, consisting of half-squares of various sizes and crosses. In another, she uses only black and orange squares, embellished with embroidered texts and crosses. In a particularly stunning piece, Tompkins uses brown and white free-form squares, overlaid with brown crosses, to create a work of moving simplicity.

In other late works, Tompkins experiments with “yo-yos” — circles of fabrics that are pinched in the center. The pieces are decorated with embroidered names, birth dates and scriptural references.

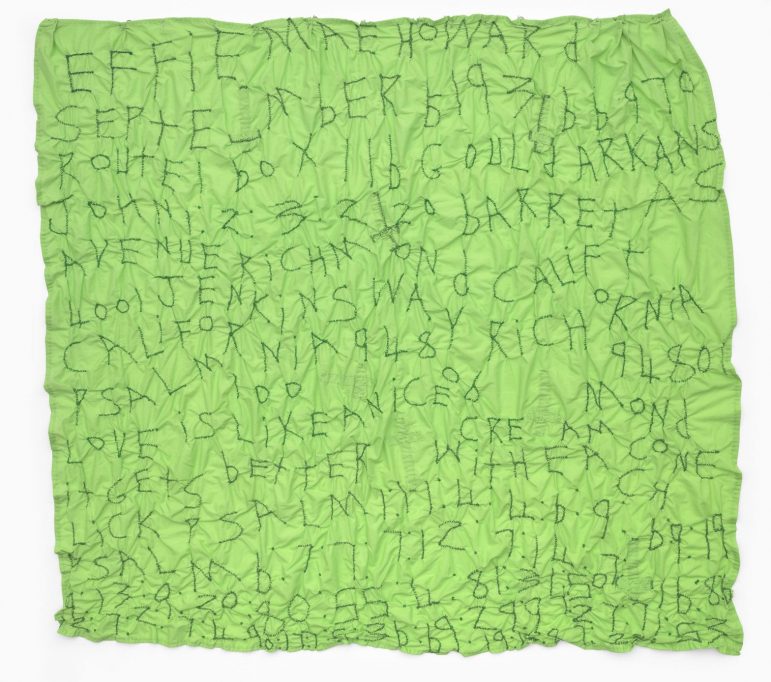

In Tompkins’s final works, she abandoned the vibrancy of multicolored creations for a single solid color. In one large piece, she embroidered the green fabric with green scriptural texts, green crosses and her personal history: her name and all the addresses where she ever lived.

The last piece, which is entirely black, consists of a large piece of pleated black fabric embellished with more than 100 large black yo-yos, lending three-dimensionality to the solid background.

* “Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective” runs through July 18 at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, 2155 Center St., Berkeley, (510) 642-0808, bampfa.org. Hours are 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Thursdays-Sundays. General admission is $10.