California lawmakers introduced several bills this year that would rezone empty strip malls and big box stores across the state to allow for new housing development without undergoing lengthy and costly local approvals.

Two are sailing through the Legislature. The other died early on. A key difference? The successful bills had the support of arguably the most powerful entity in the Capitol on housing issues, the State Building and Construction Trades Council. The other faced its vehement opposition.

The dealbreaker for the unions? If a bill did not require a “skilled and trained workforce,” which means that at least a third of the workers who can build housing on rezoned land must be graduates of apprenticeship programs. Many see this as requiring union labor, because unions run most of the state’s apprenticeships.

Affordable housing developers hoping to get units into abandoned Sears and Toys ’R’ Us stores across the state say the provision will make projects impractical in areas with low union membership, namely outside of the Bay Area and Los Angeles.

“It will be an unused law collecting dust on a shelf,” said Ray Pearl, executive director of the California Housing Consortium, an affordable housing advocacy group.

The Building and Trades Council, known in the Capitol as “the Trades,” represents more than 450,000 construction workers in 160 local unions across the state. The council says it needs the “skilled and trained” provision to grow the workforce and lift up workers who are subjected to substandard working conditions and low wages.

“You cannot address poverty and housing by driving construction workers and our families into poverty,” said Robbie Hunter, the Trades Council president. “It just doesn’t work.”

The simmering tensions between the Trades Council and affordable housing developers boiled over last year. Among the casualties was a bill to build affordable housing in church parking lots authored by Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco who is chairperson of the Senate housing committee.

Wiener said he believes there is room for compromise this year. “I know the governor, the leadership, everyone’s aware and concerned about this dispute,” he said.

But affordable housing developers say negotiations have hit a wall. And the stakes are higher than ever, with steep prices barring most Californians from buying homes and pushing thousands of people onto the streets each year. Here are some key questions that are part of the debate:

What exactly is a ‘skilled and trained workforce?’

The labor code requires that every contractor and subcontractor on a job hire graduates of apprenticeship programs for at least 30% of the workers in most trades, and at least 60% in a handful of trades. A worksite can’t make up for that ratio by having all the electricians be graduates but none of the carpenters, for example.

Apprenticeships last between three and five years on average, depending on the trade. They require several weeks of in-classroom learning, while the rest is spent on the job, where students are paid for their work. The programs are mostly free for students, typically funded by the state and union dues.

Most people enter a construction union through an apprenticeship. And 90% of students who graduate from a state-approved apprenticeship program — required by these bills — do so from a union-run program, according to data provided by the state Department of Industrial Relations.

Larry Florin, CEO of Burbank Housing, a nonprofit in Sonoma County, said the 30% requirement at worksites will be difficult for a non-union shop to implement, as it would mean recruiting workers from a union hall.

“You couldn’t even hire your own employees,” he said. “You would have to go to a third party and take who they give you.”

More than 65,000 people are enrolled in construction apprenticeships in California, according to the Department of Industrial Relations. Since 2010, nearly 67,000 people have graduated from these programs. The average graduation rate over the past five years has been 42%, according to Glen Forman, deputy chief of the department’s Division of Apprenticeship Standards.

Hunter, president of the Trade Council, said they have at least 50,000 more qualified applicants ready to enter an apprenticeship. But without “skilled and trained” requirements guaranteeing jobs on the other end, they have little incentive or ability to grow the workforce. Construction apprentices more than doubled between 2014 and 2020, driven by similar workforce requirements on large public works projects, he said.

“When the tide comes in, the boat lifts,” Hunter said. “We’re designed like that. As a need rises, we meet the need.”

For workers who make it through apprenticeship programs, the benefits are significant. According to a December 2020 study commissioned by labor, apprentices on average earned $124,000 more in wages and benefits over their careers.

What about the labor shortage?

People on both sides recognize there’s a labor crunch. A 2019 study commissioned by the Trades asserts that “California needs to double or triple its workforce employed in new housing construction” to meet the state’s ambitious goals, which range from 1.8 million to 3.5 million units by 2025.

Worker shortages vary by region and trade. In a 2019 statewide survey of general contractors, about 70% said it was difficult to find plumbers and pipelayers, while about a third said they struggled to find ironworkers. The pandemic has further tightened the labor supply, contractors and developers told CalMatters.

And the share of workers who are unionized is low. Using unpublished U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the Trades-commissioned report found less than a fifth of construction workers across California were unionized in 2017. In the residential sector, that number probably drops to the single digits, according to Dale Belman, professor emeritus at Michigan State University’s School of Human Resources and Labor Relations.

Labor advocates attribute the worker shortage to the low wages and high risks that dominate the non-union sector. Workers are aging out of the labor force, tighter immigration enforcement has reduced the workforce and younger workers have more lucrative alternatives.

Contractors with the lowest prices win bids to build housing, which Belman and other researchers say leads to a downward spiral of worsening pay and labor practices, including “rampant” cases of unpaid or underpaid wages.

“If construction is highly unstable, pay is low, no benefits, and workers are just going from gig to gig, then workers will leave when other opportunities arrive,” said Ken Jacobs, chair of the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

“The question is not about wages. It’s about which workers are eligible to work on jobs.”

AMIE FISHMAN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE NON-PROFIT HOUSING ASSOCIATION OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA

In a study released this month, Jacobs and his colleagues found almost half of the state’s construction workers’ families are enrolled in the state’s five largest public safety net programs, compared with a third of all California workers. The total annual cost to the state: $3 billion.

Jacobs says the share of worker households who rely on Medicaid or the Earned Income Tax Credit is likely much higher in non-unionized residential construction. “These are costs that really should be taken into account when we think about, overall, what is the cost of having labor standards on construction and on affordable housing,” he said.

Affordable housing developers, however, point to low unionization rates to prove the opposite point. Requiring that union workers build the state’s missing housing will constrict an already shallow labor pool, they say.

And unlike most market-rate developers, they’re already required to pay prevailing wage, or union-level wages, in many, though not all, projects that receive state and federal subsidies. According to a 2020 study by the Terner Center at UC Berkeley, about 60% of projects financed with the most common tax credit between 2008 and 2019 required developers to pay union-level wages.

“We believe in prevailing wages. So the question is not about wages,” said Amie Fishman, executive director of the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California. “It’s about which workers are eligible to work on jobs.”

While the bills with the “skilled and trained” provision would cover all housing construction of more than 10 units, it’s the affordable housing developers who say they need an exemption. They also worry that if all construction requires a union workforce, private developers won’t want to make a portion of their units affordable.

Are there enough graduates to guarantee labor supply?

State Sen. Anna Caballero, a Democrat who represents the Salinas Valley and parts of the Central Valley, said her bill to allow housing on commercially zoned land has the potential to add as many as two million housing units, citing an unpublished report.

But to turn that into reality, every potential project would need to get funding and local approval and get through other hurdles that can prevent housing from getting built.

Do the unions have enough people to build those units? “Yes,” said Augie Beltran, director of public and governmental relations for the Northern California Carpenters Regional Council. “There are people that can go and work on those projects.

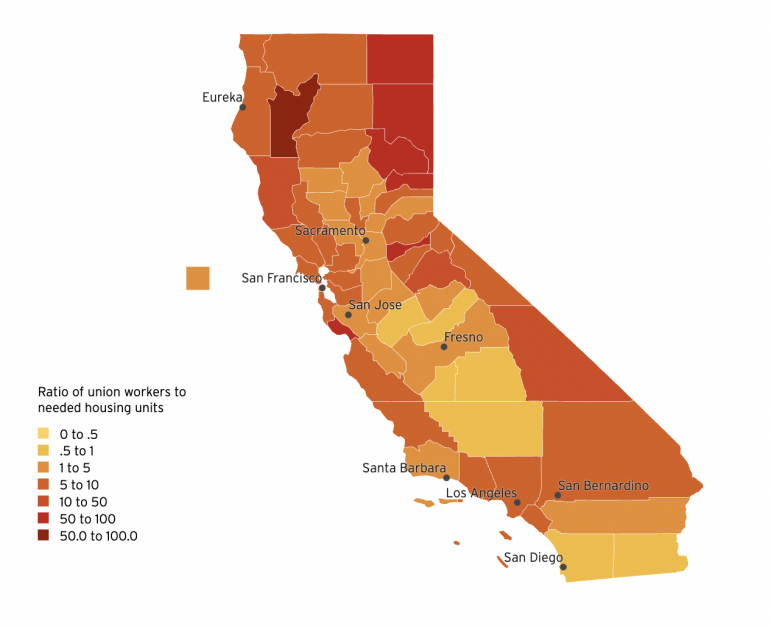

Union members aren’t always where the residential housing shortages are

The State Building and Construction Trades Council says it needs to grow apprenticeships and union membership to meet California’s affordable housing needs. See an interactive map HERE

Source: State Building and Construction Trades Council, California Department of Housing and Community Development

The Trades provided CalMatters with a map that showed the number of union members and apprentices in each county and the number of affordable housing units needed. The map shows that statewide there are about as many union members as there are low- and very low-income housing units needed; the council estimates it takes roughly one worker to complete each unit of housing.

Those numbers, however, gloss over a much more complicated reality.

First, the model assumes every union member isn’t tied up with another job. There are also regional differences: While there are 27 workers for every low- or very low-income unit needed in coastal Santa Cruz County, there’s only one worker for every three units in mostly rural and poor Tulare County in the Central Valley.

“So Trades, are you coming into the Central Valley? If you’re coming into the Central Valley, then I’m happy to start creating positions,” Caballero told CalMatters. “But if you’re not going to come in, what’s our solution? Because what I’m telling you is we don’t have enough of a workforce, and there’s a population that desperately wants training, and I want to make sure they get it.”

How does this affect racial diversity?

Eric Payne, co-founder of Central Valley Urban Institute, said recruiting efforts must improve among Black, Asian, Native and LGBTQ people, particularly from the state’s most impoverished communities, to ensure no one is left behind.

Statewide, apprentices look somewhat like the general population, according to state data. Latinos represent a majority of apprenticeship enrollees and graduates, while they make up a smaller portion of the general population. The percentage of apprentices who are Black mirrors the population. Whites are underrepresented as apprentices, but the number of graduates is on par with the population. Asians, Native Americans and Native Alaskans, on the other hand, are significantly underrepresented.

“I think the gaps exist with recruitment and being intentional about what neighborhoods and communities you’re building the pipeline from,” Payne said.

Until more apprentices graduate, the majority of eligible workers would be the nearly 500,000 existing union members. So how diverse are they? Erin Lehane, a spokeswoman for the Trades, said the council doesn’t collect demographic data.

Regional differences also worry advocates. While apprenticeship programs are booming in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, they are more scarce inland.

Julie Bornstein, the recently retired executive director of the Coachella Valley Housing Coalition, a nonprofit affordable housing developer, said the nearest apprenticeship program is 88 miles from her home.

“It becomes a universe of zero,” she said. “Because if we want to use local labor and local labor doesn’t have access, that means rural California is going to be out of luck.”

Both Newsom and the Legislature set aside at least $20 million to build up construction apprenticeships in their budget proposals, set to be finalized this month.

What would this requirement do to costs?

Just because someone somewhere can do the job, developers say, doesn’t make it feasible. Developers worry that long travel times and a lack of competition among contractors will drive up labor costs.

A developer in San Luis Obispo County, who asked not to be identified because he feared local unions would oppose future housing projects, said when he put out 34 solicitations for a job that stipulated union labor, he got only one bid, at three times the market rate.

Sen. Wiener said he had heard similar complaints among developers before pushing through a 2017 law that streamlines housing construction in counties and cities that fail to meet the state’s affordable housing goals, which required union-level wages.

“There were some folks in the affordable housing world who said, ‘We just won’t be able to use it.’ Well, they are using it,” he said.

Where are negotiations now?

In January, the affordable housing groups met with Trades president Hunter to discuss a potential compromise to move Assemblymember Richard Bloom’s bill forward. The bill called for 20% of units in rezoned retail spaces to be affordable, but omitted the “skilled and trained” workforce requirement.

In a letter provided to CalMatters, the groups presented several alternatives. Their main ask: Require that a job get at least three bids to trigger the labor requirement.

“We’re simply looking for a green light that says if you don’t get the union labor bids, you can still build,” said Pearl, from the California Housing Consortium. “And if there is labor availability throughout the entire state, that off-ramp will never be used.”

The Trades “summarily rejected” the offer, Pearl said, and has not made a counter-offer or asked to negotiate.

Hunter responded: “‘Off-ramp’ and ‘guardrail’ is the non-union contractors’ terminology for we don’t want to do it.”

Bloom’s bill died in an early policy committee hearing, after more than a dozen members of trades groups across the state said the bill would drive jobs into the “underground economy.” Bloom, a Santa Monica Democrat, declined to comment for this story, as did several developers, advocates and elected officials.

So why has it been so difficult to compromise? The Trades wield lots of power in the Capitol. Since 2015, the Trades and affiliated local unions have given more than $90 million to state candidates and campaigns, the Wall Street Journal reports.

Local trades unions have contributed at least $1.7 million to the campaign opposing the recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom, according to a CalMatters tracker. Hunter’s group has spent about $87,000 in lobbying efforts between January and March.

Besides the Caballero bill, another bill by Sen. Anthony Portantino, a La Cañada Flintridge Democrat, includes the union provision. The bill would grant incentives for local governments to build affordable housing on old retail property.

Christopher Thornberg, founding partner of Beacon Economics, said attempts to build more housing die “by a thousand cuts” in the Legislature. He worries the skilled and trained workforce requirement represents another cut.

“You’re not hurting the rich,” Thornberg told CalMatters. “You’re hurting lower income folks because they’re the ones getting crushed by high housing costs.”