California’s community colleges face a reckoning over losing vulnerable students to more expensive for-profit colleges, where they often incur a disastrous amount of debt but exit with no degree.

Designed to be affordable and local, community colleges are being outmaneuvered in marketing by the state’s for-profit college industry, which despite its troubled past, spends heavily on television advertising to lure students, experts said.

Black people, Native Americans and Pacific Islanders are increasingly choosing for-profits, either by enrollment or transfer, at much higher rates than those groups’ shares of the state population. They are enrolling despite abysmally low chances of graduating within six years, according to federal data. Nearly 9 out of 10 Black and Native American enrollees don’t earn a degree at for-profit colleges in that time.

The industry has a history of students racking up high-interest loans from lenders who are sometimes affiliated with the school. In one such scheme, former state Attorney General Xavier Becerra called the degrees students were pursuing “worthless.”

Community colleges are the answer for these students, experts said, but the locally run public schools have to do a better job at helping students obtain financial aid and being more welcoming and supportive of underrepresented students throughout their academic lives.

Not all the blame should fall on the for-profit schools, said Gregg Irish, executive director of the city of Los Angeles’ Workforce Development Board and co-chair of the California Community Colleges Black and African American Advisory Panel.

“Black students are walking with their feet and making choices. I am not saying they’re making the right choices, but it means that maybe their needs aren’t being met” at community colleges, Irish said.

Unemployed people may not want to wait, or simply can’t wait for a semester to begin to train for new work, he said. Some for-profit schools let students begin class the day they enroll, Irish said.

For-profits, he added, have “open entry, open exit, flexible schedules, few admission requirements. They capture the interest of people who are sitting home and believing they can’t traverse the system of community colleges.”

Students are often susceptible to such pitches, even though the schools offer degrees that “are not respected” in academia or professional circles, said Pedro Noguera, dean of the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California.

Community colleges simply need to do more, Noguera said: “They are in trouble if they don’t.”

Community college leaders acknowledge that they must do better, but the system doesn’t appear to be taking any meaningful steps to challenge the for-profits, which not only engage in aggressive television marketing but also offer students fast admissions and easy money from private loans.

Community college officials acknowledge that navigating their system can be difficult.

The for-profits “do a good job at taking the administrative burden off students and easing the path into their institutions,” said Paul Feist, vice chancellor for communications for the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. “We have to be humble enough to acknowledge that and to do better.”

The 116-college system has more than 2.1 million full and part-time students – the nation’s largest student body — and is divided into 73 local districts governed by elected trustees.

The Community College system estimates the average tuition for in-state students is $1,458 annually. The website College Tuition Compare estimates the national average of tuition at a for-profit college is $16,186.

The for-profit industry has long claimed it fills an educational void left by public and private nonprofit colleges.

Robert Johnson, head of the California Association of Private Postsecondary Schools, a group that represents the for-profit industry, and Rick Wood, president of the association’s board and CEO of the Institute of Technology, which has campuses in the Central Valley, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

For-profit schools “provide an alternative to a long-term degree program at a traditional university,” the association states on its website. Schools offer “more focused educational training at a faster pace, often without the optional general education courses that may not be occupationally related to the career goal of the student.”

A growing trend

One of the ways that the for-profit college industry attracts students is simply by making them feel welcome, said former student Don’Andre Adams, 34, who chose a for-profit over a community college.

When he enrolled in ITT Technical Institute in San Bernardino to study computer technology in 2013, he was so excited, that “it was almost as if I got accepted to a Yale or Harvard.”

Adams came from what he called “unstable situations” and was homeless for a time. “I never had a proper introduction as far as college goes, and what I would need to take” to prepare for it.

Adams, who is Black, was typical of the students lured to for-profit colleges in search of job-ready skills. He was drawn to the school by “a strong interest in computers and learning software,” he said.

Nationally, for-profits did better than public colleges in enrolling and retaining students during the pandemic. While community colleges lost 12% of their students this spring, the for-profits lost only 1.5%. In 2020, while community college enrollment plummeted, the for-profits saw a 3% increase, according to the National Student Clearinghouse which collects data directly from colleges nationwide.

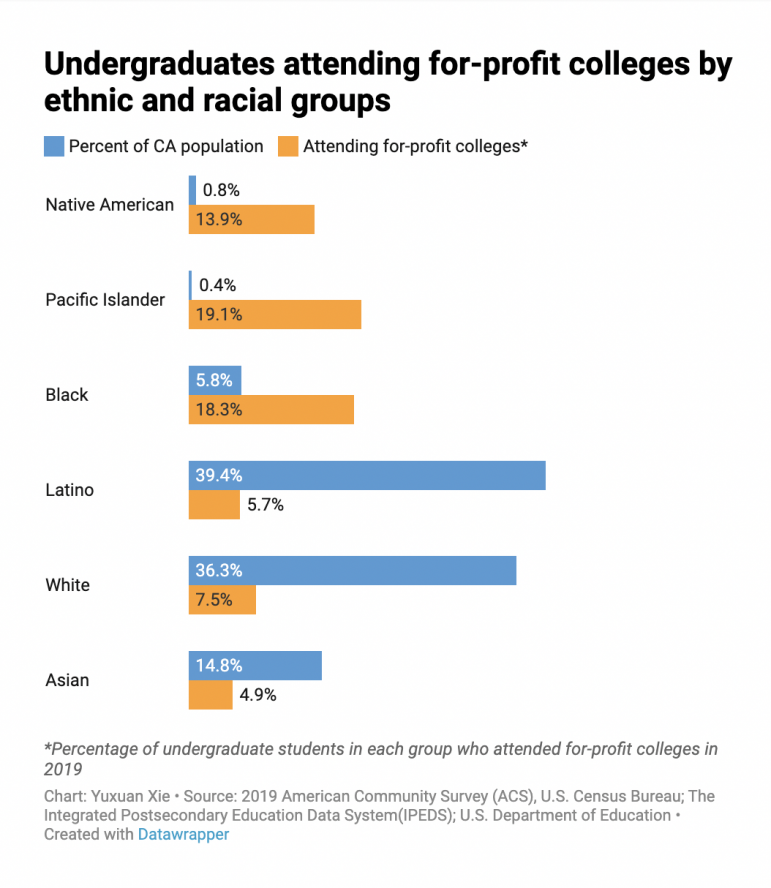

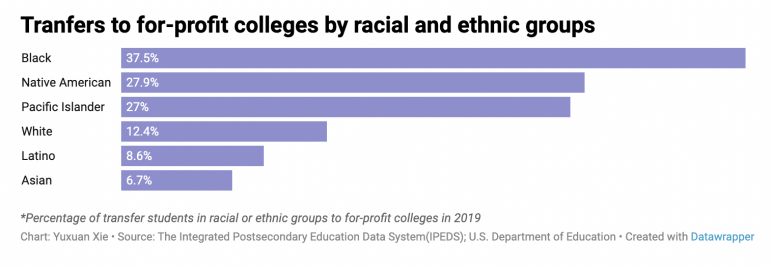

The student groups increasingly enrolling in for-profit colleges make up small portions of California’s population – 6% are Black people and less than 1% are Native American and Pacific Islander. But these students make up larger shares of for-profit undergraduates: 18% are Black, 14% are Native American and 19% are Pacific Islander, federal data show.

It’s a growing trend: Nearly 38% of Black students who transferred to colleges within California in the 2018-19 academic year went to a for-profit school, a rate that more than doubled from two years earlier. For Native Americans, the transfer rate was 28% and for Pacific Islanders nearly 27%.

The three groups are fighting “some of the same forces” that limit their educational options, including disparities in K-12 preparation for college, said Vikash Reddy of the Campaign for College Opportunity. Reddy highlighted the disproportionate numbers of Black students attending for-profit schools in the organization’s report on The State of Education for Black Californians, which was issued in February.

Another attraction to many of the for-profits is the ease of admission even for students who otherwise may lack the credentials to be admitted to a four-year school in California’s public university system.

Adams didn’t realize that ITT had open enrollment as part of a business plan to force students to take private loans from a lender affiliated with the school. He thought he was accepted because of his 2.2 high school GPA.

He was one of tens of thousands of enrollees at 149 ITT campuses across the country who were part of what was described in state court documents as a scheme to ensnare students in high-interest loans.

The school’s tuition was 10% more than the maximum amount of financial aid students could receive. School officials then pushed students to make up the difference by borrowing, according to court documents.

The school used “a variety of aggressive tactics, such as pulling students from class, withholding course materials or transcripts, and rushing students through financial-aid appointments,” to get them to take the loans, the California Department of Justice charged in a lawsuit settled in 2020.

“Many ITT students did not understand the terms of their private loans, and some students did not realize they had taken out loans at all,” state Justice Department lawyers wrote in court filings.

ITT shut down abruptly in 2016, leaving students like Adams without a degree and loans to pay – in his case about $52,000. What’s more, his credits from ITT weren’t transferable.

Eventually, Adams was one of 43,000 students nationwide, including 4,000 Californians, whose student loans through ITT were forgiven in a settlement involving 48 other states and the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Former California Attorney General Becerra helped broker the $330 million settlement that shut down ITT’s affiliated loan company, PEAKS.

“ITT Tech saddled students with massive debt, exorbitant interest rates, and a worthless diploma,” Becerra, now U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, said at the time.

Debt but no degree

One of the lures that for-profit schools continue to dangle to prospective students is immediate financial aid, said Audrey Dow of the Campaign for College Opportunity.

That aid, through private loans, “is coming quickly and addressing some immediate financial needs (students) might have,” Dow said. “It’s not just aid for their tuition, but really it’s aid for them to live, money for rent, for transportation.”

Those loans, though, come at a high cost. “On the back end, those students will have tremendous debt,” she said.

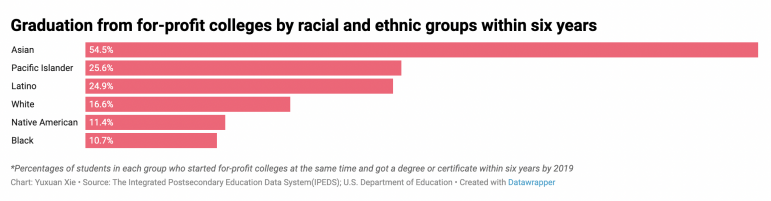

Choosing a for-profit school ends badly for the vast majority of Black, Native American and Pacific Islander students, federal Department of Education data shows.

Slightly less than 11 of Black students and 11% of Native American students achieved degrees from for-profit schools after six years, according to data of California students who all began college at the same time and either graduated or dropped out by 2019, federal data shows. Looking at all students in the six-year group, 22% of for-profit students achieved degrees.

Members of the three groups who attended community colleges each had better success rates over six years than those who attended for-profit schools, 2019 data from the state Community College Chancellor’s Office shows.

Black community college students either graduated, transferred or obtained a certificate at a rate of nearly 40%, the data shows. For Pacific Islanders the rate was nearly 41%. For Native Americans it was 35%. The six-year cohort from which that data is drawn ended in 2018. It is the latest data available.

Quick and nimble

For-profit schools simply outgun community colleges in the marketing game, experts said, and pose as the best choice for students on the fringe.

In both high school recruitment and luring transfers, for-profit schools spend lavishly. They pitch schedules convenient for working adults, financial-aid packages, private loans and quicker routes to degrees and paychecks.

When “new technology comes along, boom, (for-profits) do it. They have it,” said Devon Graves, a California State University, Stanislaus professor of education, kinesiology and social work who studies community colleges.

That’s attractive to students who “focus on the now” and are drawn to schools “that innovate and move quickly.”

The for-profit schools also target students who may be poor, immigrants, and from families where no one has gone to college. “Students who don’t come from a privileged background may not understand and make a connection” to being defrauded, Graves said.

In mid-May, the community colleges’ Chancellor’s Office filmed a series of public service spots aimed at recruiting and retaining Black and Pacific Islander students.

Still, neither the state office nor the local districts that run the colleges can afford to match the for-profits in spending on television ads, Feist said. The new spots will appear online and on streaming TV such as Hulu.

Fixing the problem is also going to require more outreach to underrepresented students and increased mentorship and counseling, Feist said.

“Marketing alone isn’t the answer.”

Nothing free about it

Critics have long railed against the for-profit industry’s slick marketing and poor educational quality. A 2012 U.S. Senate report found for-profit colleges spent more money on advertising and recruiting than on instruction and that schools made more money in profits than they spent educating students.

Situations like Adams’ are ones that school counselors can flag and work to prevent, said Enrique Espinoza, a high school guidance counselor at Tustin Unified School District in Orange County and a doctoral candidate at the University of California Riverside. It’s a familiar scenario.

One of his students, the child of immigrants, was thrilled to announce he’d gotten what he called “a full ride” to a for-profit college, Espinoza told EdSource. “Full ride” is a phrase often used to describe athletic or academic scholarships. The student thought he’d earned a scholarship. But Espinoza said he’d never heard of a for-profit school giving anything away for free.

He met with the student and his parents. What the student had thought was a scholarship was really an aid package laden with high-interest loans that would have to be repaid.

There was nothing free about it. Community college was a better choice. Espinoza worked with the student to enroll him at Santa Ana Community College’s automotive technology program at a much lower cost.

The Community College system estimates the average tuition for in-state students is $1,458 annually. The website College Tuition Compare estimates the national average of tuition at a for-profit college is $16,186.

While community colleges are the wiser choice for students seeking vocational education, Espinoza said, the colleges don’t do enough to sell themselves to students.

“They need to be more visible,” Espinoza said. Some high school students either don’t know about community colleges or associate a stigma with the colleges as local institutions, he added.

Student applicants drop

Black students may be pulling away from community colleges before the application process is even complete, state officials said recently.

Calbright, the fledgling statewide online community college, is able to track applications and can flag when prospective students fail to complete them, Calbright President Ajita Talwalker Menon said during a recent trustees meeting.

All community colleges use the same online application portal. It could also be used to see who doesn’t finish applications so that those persons could be reached, said Pamela Haynes, president of the state board of community college governors, which oversees the system. Commenting during the Calbright meeting, Haynes said there has been no intervention with those would-be students, but that could change with plans to upgrade the computer system.

Black people “are probably one of the largest populations that just walk away” from applications, Haynes said. “If they are doing that at Calbright, they are doing that at the other 115 campuses.”

The application portal, run by a third-party vendor, “is cumbersome, has few prompts and is not user-friendly,” Haynes told EdSource.

Chancellor Eloy Ortiz Oakley has prioritized revamping the system, she said. If it “is not fixed, it really stymies all the strategies and outreach.”

But strategies and outreach also need to be improved, said Edward Bush, president of Cosumnes River College in the Los Rios Community College District in Sacramento.

“Oftentimes, we underestimate the savviness of our students,” Bush said. “They know they are paying more” at for-profit schools. “They know they are going to accumulate a greater level of debt,” he added.

But despite that, “they believe the trade-off is the right idea. We could argue that much of that may be rooted in false promises, but at least they are sold on a promise.”

When community colleges can make the same promises — and deliver on them — the students will stay, Bush said. Students need to be able to say to themselves, “I am going to be able to get the class that I need when I need it” and have it happen.

Finding his way

Don’Andre Adams said he has long since realized the warm welcome that ITT Tech gave him was all part of a ploy to enroll him in a program that he hoped would lead to a technology career.

He chose the school over community college because he also believed it was a more serious place, he said: “I can easily get distracted. I didn’t want to be someplace where I could easily fall behind.”

To Adams, the biggest sin was preying on his naiveté at the time by convincing him the school was legitimate and the best choice for someone with his background. But Adams recovered. He eventually took classes at Chaffey Community College in Rancho Cucamonga and now works for the Boys and Girls Club of Redlands as a youth development specialist.

He will soon enroll at California Baptist University in Riverside, a private, nonprofit school of 11,000 students with the ultimate goal of earning a doctorate in psychology so he can open his own practice.

EdSource data journalist Daniel J. Willis contributed to this report.