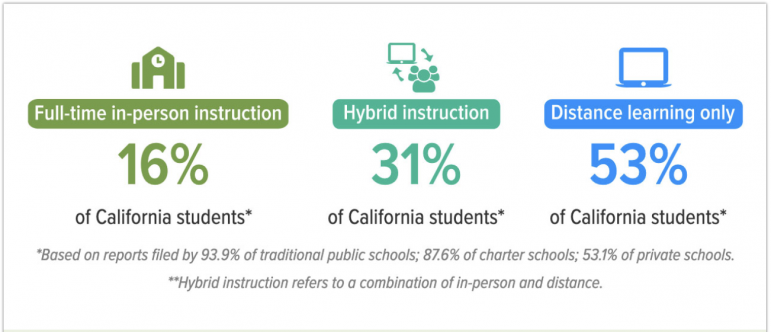

Although 87% of California’s traditional public schools have reopened for some form of in-person instruction, fewer than half of students have returned either full time or part time in a hybrid model. A total of 55% of all public school students, including those in charter schools, were at home, in distance learning, as of April 30, according to an EdSource analysis of new data released by the state.

EdSource found that two-thirds of students in district schools with the largest proportions of low-income families were in distance learning, compared with only 43% of students in schools with the fewest low-income families — a disparity that may partly explain a widening learning gap between wealthy and poor students that researchers and teachers suspect the pandemic has enlarged.

Higher Covid rates in poor communities contributed to the disparity. Parents in highly infected areas have been reluctant to send their children back to school, and teachers in those areas resisted returning. Parents in low transmission areas, meanwhile, pressured school boards to reopen.

“The data shows complex connections to a variety of issues that ultimately disadvantage poor kids,” said Kevin Gordon, president of Capitol Advisors Group, a school consulting firm. “Even though the state has made an effort to send more dollars to poor schools, poverty has determined who has had more educational opportunity than not.”

Search and explore new data here on the status of in-person, hybrid and distance learning at public, charter and private schools using Edsource’s interactive maps, charts, and searchable database.

Only 13% of public school students and 12% of charter school students have resumed a normal five-day-a-week school schedule. Here again, there were wide differences by income. Traditional public schools with the least number of low-income families had more than three times the percentage of students attending full time, in person than schools with the most low-income families. Those wealthier schools had a larger proportion of students in hybrid as well.

A comparison of two Oakland schools, each with 380 students, one in a low-income neighborhood and the other in a wealthy neighborhood, illustrates a stark disparity. At Esperanza Elementary, where 96% of students qualify for free and reduced-price meals, 23% of students are participating in the district’s hybrid model offering a few hours a week of in-class instruction. At Hillcrest Elementary, where only 11% of families qualify for free and reduced-price meals, 80% of students are taking advantage of in-person instruction.

The disparities are not surprising and are “a symptom of a problem that predated Covid,” said Christopher Nellum, interim executive director of the Education Trust-West, a nonprofit advocating for low-income youths. Many low-income parents who have borne the brunt of the pandemic “are not sending their children back for a lack of trust in the education system.” Despite assurances, they’re worried about the spread of infection. “They’re asking, ‘Will they really be safe when they return?’” Nellum said.

Dr. Naomi Bardach, who leads the Safe Schools for All Team for the California Health and Human Services Agency, said that state officials recognize that families in communities hit the hardest by the pandemic are hesitant to have students return to school.

“Supporting these families and students is our focus and imperative,” she said. Strategies include committing $1 million to engage parents where reluctance is highest, she said.

EdSource’s analysis of state data also shows huge differences among regions of the state. While two-thirds of students were in distance learning in the two biggest urban regions — the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles County (down from 83% with the start of hybrid learning in Los Angeles Unified) — only a third of students were in distance learning in rural northeast California.

Distance learning in other regions include 45% in Orange County, 43% in the San Diego-Imperial Valley region and 62% in the Inland Empire, which includes Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

EdSource’s database and interactive map is the first analysis of the status of campus reopenings, which the Legislature mandated in March when appropriating $6.6 billion in K-12 Covid assistance through 2022-23. Every two weeks the state’s 13,667 private, charter, traditional district and county-run schools are supposed to report to the state how many students are in distance learning, in a hybrid model or in school full time, defined as five days each week.

The most recent report provided to EdSource was dated April 30. It should include attendance at least through April 26, the last reporting date, although some districts and schools update their numbers more frequently and others have been weeks behind in reporting.

The new state data provide actual numbers of students who have returned to school from the 94% of district schools, 88% of charter schools but only 53% of private schools reporting so far. State officials caution that the self-reported numbers contain errors. Data from San Bernardino City Unified, the state’s ninth-largest district, for example, could not be included because of a clerical error. State officials say accuracy should improve with each update.

EdSource’s findings include:

- Among students in traditional public schools, 54% are in distance learning; 33% in hybrid; 13% in full, in-person instruction;

- Among students in charter schools, 63% are in distance learning; 25% in hybrid and 12% in full, in-person instruction;

- In private schools: 61% of students are back five days a week; 19% are in hybrid and only 20% are in distance learning;

- Among traditional public schools, more middle and high school students are in distance learning (59%) than elementary school students (47%). Of those who have returned to school, 31% of middle and high school students are in hybrid and 10% are back full time, while 36% of elementary students are in hybrid and 18% are back full time;

- Divide schools into quartiles based on the proportion of low-income families, and the pattern is clear: In the quartile with the least number of low-income students, 43% of students are in distance learning; in the quartile with the most, it’s 66%.

- In April, the number of students solely in distance learning declined. Between the April 20 and April 30 reports, students learning remotely exclusively fell from 61% to 54% in traditional district schools and from 69% to 63% in charter schools.

That incremental change has been too slow for parents who have called on Gov. Gavin Newsom to demand that schools fully reopen. “The facts prove the California Legislature’s reopening efforts were a failure. Despite what Gov. Newsom says, a majority of public school kids are not physically back in school in California,” said Megan Bacigalupi, spokeswoman for Open Schools California, a grassroots organization that has called for an immediate return to pre-Covid, full-time instruction.

At the same time, there are also families that say their children are thriving under distance learning. Alex Cherniss, superintendent of Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified, serving a wealthy community in Los Angeles County, reports that a quarter of parents recently surveyed said they’d choose distance learning next year if the district offered it.

A survey last month by the Public Policy Institute of California found that 397 parents had mixed views toward school reopening: 21% said schools were moving too quickly; 37% said schools were moving too slowly, and 41% said the pace was about right.

Hesitancy in hardest-hit communities

Edgar Zazueta, senior director of policy and governmental relations for the Association of California School Administrators, said the low numbers of students returning to campuses in hard-hit areas are consistent with what district leaders have reported and surveys of parents’ choices indicated.

Higher rates of infection also contributed to protracted negotiations in districts with strong employee unions, he said. Some districts, like hard-hit San Bernardino Unified and Santa Ana Unified, will remain in full distance learning the rest of the year, while Fremont Unified in the Bay Area couldn’t reach a deal to return. Others, like San Francisco Unified and West Contra Costa Unified, were slow to open with hybrid programs in part due to the lack of teachers willing to volunteer to return to campuses.

When given an option to return, many parents and high school students where the pandemic raged have declined for multiple reasons. Vito Chiala, principal of Overfelt High School in East San Jose, where pre-pandemic attendance had been 95%, said, “It’s not that students don’t want to come back. Some are nervous about mingling and mixing with their kids. Another group has been taking care of siblings while their parents work and want to make sure they’re logging into middle and elementary schools.”

And a third group of students, he said, are working, sometimes taking their computers with them. “I can’t answer now. I have a customer,” one student told a teacher, Chiala said.

Overfelt and other East Side Union high schools have been offering one 90-minute period each week, outside of the distance learning schedule, where a cohort of students can choose one teacher for in -person help.

Beyond academic assistance, he said, “it’s an opportunity to get out of the house for social interaction and is important from a mental health perspective.” Yet only 20% of the 1,450 students have taken up the offer.

In late March, at Newsom’s urging, the California Department of Public Health lowered the recommended social distancing between students from 6 feet to 3 feet, making it theoretically possible to open up many schools with full classrooms of students. But by then, Zazueta said, many districts had negotiated the previously recommended 6-foot distancing and didn’t try — or couldn’t quickly convince labor unions — to adopt the new standard. More space between students required a hybrid model, with split shifts or alternate days. Parent groups across California filed a half-dozen lawsuits demanding a return to daily in-person instruction, with mixed results (see here, here and here).

HOW THE SCHOOL REOPENING ANALYSIS WAS DONE

All data comes from the California Department of Public Health, based on figures provided by school districts and charter and private schools. EdSource has attempted to note any school or district with obviously erroneous data. If any data appear to be incorrect please contact the school or district affected to report the issue, and let us know at edsource@edsource.org.

Full-time in-person is defined as full-time instruction at school sites five days per week.

Distance learning only is defined as students who at no point go to school sites for instruction.

Hybrid instruction refers to students who get some instruction in person and some via distance learning.

Percentages are calculated by dividing the number of students the schools report in each learning mode by their reported total enrollment.

“Low income” refers to the percentage of students who qualified for free or reduced-price meals in 2020. EdSource categorized the total number of schools in California by dividing them into quartiles. In the highest quartile of schools, more than 83% of students were eligible for free and reduced- price meals. In the second highest quartile, over 66% were eligible. In the third highest quartile, over 38% of students were eligible for the meal program, and in the lowest quartile under 38% were eligible.

In December, Newsom first proposed using $2 billion in unexpected state funding as an incentive for districts that agreed to bring back elementary school students for in-person instruction. To qualify for the money, districts also had to bring back at least one grade in middle or high school and cohorts of students with the most pressing needs, including English learners, homeless students and those without internet access.

By the time the Legislature agreed, in March, Congress had passed the American Rescue Plan Act, which awarded $15.2 billion to California’s K-12 districts, and Newsom and the Legislature added $4.6 billion in K-12 state Covid relief for all districts. Next to the $20 billion in new money, $2 billion may have lost some of its luster for some districts. And a lateness penalty, docking funding by only 1% for every instructional day missed after April 1, may not have prodded them to expedite reopening.

In announcing the program on March 1, Newsom expressed optimism that after schools opened initially, parental confidence would grow, as would pressure to expand in-person hours to more students.

In March, Newsom said that 9,000 of 11,000 public schools — more than 80% — either have opened or planned to. The latest data, with 87% offering either hybrid or full-time in-person instruction, proved him right.

“By prioritizing school staff for vaccines, taking early action to unlock billions of dollars in support, and providing direct assistance to hundreds of school districts, we have worked with local leaders to get the vast majority of schools to offer in-person instruction,” Bardach said.

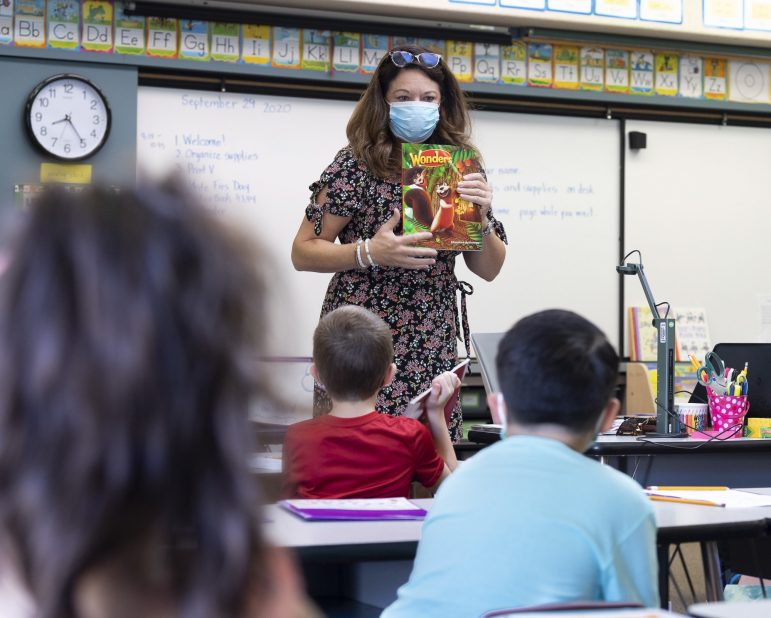

But Newsom and the Legislature didn’t set minimum requirements for a hybrid model and in-person instruction in order for districts to qualify for the money. In Modesto City Schools, elementary school students attend four days a week, with one day remotely. In Oakland Unified, in-person instruction is a couple of afternoon hours two days each week. In West Contra Costa Unified, in-person instruction is four hours for K-8 and five hours for middle and high school students three days a week. In East Side Union High School District, it’s two hours a week. In Los Angeles and other districts, high school students have returned to school classrooms to watch their teachers from their own homes teach them on Zoom.

Some parents aren’t seeing enough benefit from a few hours of socializing and instruction to justify the logistics and the risk of in-person instruction — another reason distance learning remains prevalent with a month left in the school year.