NFTs — those magical beans that can supposedly transform the dross of digital artwork into strands of gold — may also have the power to turn a social network into a platform for creative people to make creative income.

The basic economics of social media are not hard to understand.

Social media companies make the bulk of their money by selling ads to online advertisers.

Advertisers pay for their ads to appear on platforms that have large audiences.

Audiences are drawn to platforms where users post interesting, engaging, attention-grabbing content.

The creators of that content — the photographers and artists who post to Instagram, the journalists and writers who link their work to tweets, the dancers and choreographers who entertain on TikTok — are largely uncompensated for what they create.

And while the content creators get the psychological capital of likes and follows, it is Instagram, Twitter and TikTok that get the money.

It is a great system for large social-media companies, but if one cares about the creators, it is a problem.

Katie Geminder — it rhymes with reminder — has she appeared in many important moments of tech history.

Between 1999 and 2012, she worked in succession at Amazon, Apple, Facebook, MySpace and Zynga.

Her LinkedIn profile says that she has spent most of her career in user design and experience, though that doesn’t cover all her roles. She says she works in the “sweet spot between qualitative and quantitative.”

“I’m an empath, so I feel,” Geminder says. “I can put myself in someone else’s shoes and experience a product, and I think that’s where my mojo comes from.”

Though she doesn’t consider herself a techie — she says she’s “numbers dyslexic” — a search on the website Justia returns her name on a series of patents beginning in 2006; in each, she is listed as one of the inventors, along with Mark Zuckerberg and a handful of others.

“One of the things I’m good at is being a translator and taking complex ideas and distilling them down so that anyone in the company can understand it,” she says.

That’s a key skill in the emerging world of NFTs where Cent.co, the San Francisco startup that Geminder co-founded, is making its mark.

“There’s a big froth around NFTs and crypto and blockchain,” Geminder says. “My personal opinion is it all gets munged together in a way that is not helpful.”

The different components have to be separated and understood individually before the combination makes sense.

“I had to do that for myself,” she says, “before I actually pushed my chips all in.”

Over the last several months, the public has been inundated with stories about digital artists scoring head-scratchingly large paydays by selling NFTs to buyers besot with auction fever, though what is being sold and why someone might want to buy one have been harder to understand.

One reason is that when people explain NFTs, they are forced to use analogies to the workings of the tangible world. But analogies only go so far; NFTs and their cousins, cryptocurrencies and blockchain, are creatures of the digital world, intangible by nature and endowed with characteristics not always found in our tangible, physical space.

In some ways, blockchain is the easiest one to explain. When people talk of blockchain they are generally referring to a “public” computer program that runs on computers all over the world. No single user or company or organization controls the program. Instead, a decentralized community of computers constantly attends to the chain, processing and verifying transactions.

A new “block” of computer code can be added to the chain, but only at the end of the program.

In order to add a new block, some number of the computers on the decentralized network have to process the code and validate and confirm its integrity. Those computers — or those who own those computers — are often called miners, and they get paid for their work.

How are miners paid? When the blockchain was created, the issuance of intangible units of value referred to as tokens or coins were programmed into the chain, and those tokens or coins are referred to as a cryptocurrency.

The blockchain that was used to create the first cryptocurrency — Bitcoin — was designed solely to create a decentralized system of currency that would be a store of value and would operate independently from the centralized currencies of the world — the dollar, the euro, the renminbi — that are generically referred to as “fiat.”

But a blockchain need not be used solely to create and support a currency. Other public blockchains were built to do many things, and this has created a foundation for a new decentralized type of worldwide computing network.

Ethereum, like Bitcoin, is a decentralized public blockchain. Ethereum was designed to facilitate “smart contracts” that allow transactions to occur automatically when a specific set of predefined conditions occur, as long as the required number of computers maintaining the network reach consensus that the conditions have been satisfied.

Thus, instead of a single network owner authorizing a transaction, it occurs simply as a result of the predetermined conditions being fulfilled. This functionality allows Ethereum to be used for purposes far beyond supporting a currency.

But that is not to say that there is no currency on the Ethereum blockchain. Computers on the Ethereum network still need to be incentivized to process transactions, and on the Ethereum chain, that incentive is the opportunity to earn Ether — the native coin of the Ethereum blockchain.

Crypto coins are intangibles, but it should be no surprise that intangible coins can have value as measured in fiat. The miles that frequent flyers earn by flying or the points that frequent shoppers accumulate by using their credit cards — are each digital currencies of a sort — and they can be exchanged or traded or used to buy tangible items.

Just before COVID-19 locked the world down, Geminder took two trips. First, she went to Svalbard, far in the northern reaches of Norway, about as close as you can get to the North Pole without joining an expedition.

During the six days she spent there, Svalbard was dark for 24 hours a day. It wasn’t intentional — Geminder concedes there were some failures of due diligence in the planning stage — but it had an important result of forcing her to spend a week in darkness.

“I think that weird pattern-interrupt absolutely reprogrammed my brain,” she says.

Not long after, she traveled to South Africa — where she was held up at gunpoint in a camera store — before jumping off on a trip to see mountain gorillas in the wilds of Uganda.

Perhaps conditioned by the days in Norway’s darkness and the “weird, weird” encounter in South Africa, some of the things that she saw in Uganda hit her in a deep and emotional way.

Hiking in the backcountry, she saw local craftsmen and women creating carvings and renderings of exquisite quality, but being paid pennies for their work. She saw an entire country where people were conducting all of their affairs on their cell phones. No one used cash; money moved back and forth exclusively on a digital platform.

She returned to the States on March 13, 2020, just as the full force of the pandemic was bearing down on the Bay Area. She quickly saw its powerful, destructive force unleashed in her home community.

As the pandemic blanketed the area, she saw creative people stepping to the forefront to do things for others — making masks, delivering food, caring for the most vulnerable — but all of the creatives she knew — artists, musicians, photographers — had been supporting their creative passions by working in restaurants and coffee shops and bars and galleries. And now all those jobs were shut down.

“Everything just swirled into focus for me.” She had an epiphany.

Creative people needed a platform where they could support themselves through their creative work.

NFT stands for “non-fungible token” and, in that respect, it is fundamentally distinct from the tokens that are cryptocurrency. Coins are designed to be fully fungible.

Non-fungibility is an NFT’s superpower. Each token has a single unique identifier that — once connected to a digital asset — creates something that didn’t heretofore exist in the digital world.

Because digital assets were infinitely duplicable, and each duplicated copy was an exact replica of the one from which it sprang, digital assets were all the same.

A digital recording of Bob Dylan’s “Positively 4th Street” and a digital copy of that recording were but two manifestations of the same thing, neither with greater dignity than the other. And the owner, absent copyright limitations, could create an infinite number of exact duplicates, meaning that the value that scarcity adds to an asset did not attach to digital assets.

With NFTs, that proposition has changed.

Before she left on her travels, Geminder had been advising a San Francisco company called Cent. Cent began in 2017 as a social network for digital artists to share their work and a place fans could follow and support that work.

Cent was experimenting with ways that the artists could monetize their work.

The company’s co-founder, Cameron Hejazi, described Cent’s initial idea as building a new social network on which all “the actions that you do on a social network, like posting, replying, liking, retweeting … [would be] all incentivized so that when a user took a particular action in some way, there was financial value bundled with that action.”

Then Geminder and Hejazi considered if there was a way you could monetize work already posted to an existing social network.

That led to an improbable-seeming hypothesis: There might be a market for people to buy and sell tweets, if the tweets were turned into NFTs.

They imagined that buying a tweet would be like getting an autographed baseball card. The NFT would contain an immutable digital receipt that showed who was the one unique owner of that tweet.

Like a baseball card, the NFT could be traded or sold or held forever as a precious collectible.

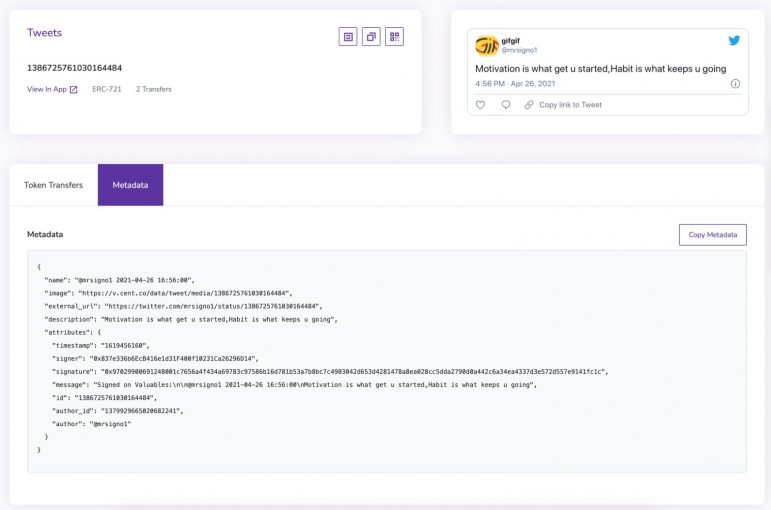

To test the idea, Cent lashed together an app called Valuables that sat on top of the Cent network and allowed users to buy and sell tweets.

Valuables went live in December of 2020.

At the beginning, it was all an experiment. Their conjecture was that a fan would “collect” the work of a favored creator by offering to buy a tweet. The app allowed competitive bidding, so there was the possibility of multiple bids for a tweet. If an offer was accepted, the tweet would be “minted” into an NFT, and the blockchain would then hold an immutable digital receipt that showed that the buyer was the one unique owner of that tweet.

Other people could still access the tweet on Twitter, but only one person owned the original tweet. It was like having the first edition of a book; the book was the same as the book in every other edition, but more valuable because no more first editions could be created.

The concept seemed to work. People were using Valuables. They were actually bidding for tweets. Ether — the unit of payment on Valuables — was changing hands. Not lots of money, but proof of concept.

Then something transformative happened.

Someone on Valuables offered to buy the first tweet that Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter, ever tweeted: the March 21, 2006, tweet that said, “just setting up my twttr.”

Multiple users lobbed in bids. The price escalated.

Dorsey closed the auction by accepting an offer of $2.9 million in March of 2021, almost exactly 15 years from his tweet’s initial posting.

It was a big deal for the startup.

Geminder says, “my head exploded.” The best part was that it didn’t happen because Cent pitched the idea to Dorsey. It just happened organically.

And the icing on the cake was that Dorsey donated the proceeds of sale to COVID-19 victims in Africa.

Cent created the future rules and terms for the sale for NFTs on its platform. On the first sale, Cent retains 5%, and the creator takes 95%. On a subsequent sale, Cent gets 2.5%, the original creator gets 10% and the seller gets 87.5%. If over the years a tweet is sold and resold a dozen times, the creator will keep getting 10% of each sale price, a continuing royalty.

The Twitter application is just one area of experimentation. Cent is raising funds to create additional apps to allow creators on other platforms to monetize their work by minting them as NFTs. Hejazi thinks of it as a way to give creators the tools — whatever platform they are working on — “to be able to unlock the value through NFTs.”

The blockchain is flexible; any digital work of art — a song, a story, a drawing, a video — can be minted into an NFT and made available for sale and purchase.

NFTs make digital assets collectable. Put differently, from an investor perspective, NFTs are a new class of assets.

Teddy Fusaro is the president of San Francisco-based Bitwise Asset Management, a “specialist cryptocurrency asset management firm” that serves as an asset manager for cryptocurrencies.

Bitwise creates and manages funds that invest in cryptocurrencies. Its investors are “accredited investors” — pension funds, trusts, high rollers, family offices — that want to get in on the potentially lucrative world of cryptocurrencies.

Bitwise makes it relatively easy for investors who are not comfortable with the arcane ecosystem to participate. Bitwise handles the technical work of managing the digital assets for the funds and investors.

“Our investors don’t tend to be the 25-year-old whiz kid who’s good at figuring out how to invest in crypto on an app,” Fusaro says. “It tends to be a more experienced investor or a financial adviser or an institution that wants to get some exposure to this emerging asset class, but they’re not going to download an app from the App Store and wire money into it to figure out how to hold Bitcoin.”

Fusaro jokes that Bitwise is an “education company” with asset management added on because “anything that pops up in this crypto economy just requires so much education to those who are coming into it for the first time. And there’s always something new.”

According to Fusaro, Bitwise is one of the largest players in the space. So far Bitwise doesn’t invest in NFTs but he is fielding a lot of questions from investors about them.

Non-fungibility makes NFTs very different from investing in crypto. Each NFT is different, and so each one has to be analyzed individually to understand what a buyer gets. Many of the parameters haven’t been fully worked out. “We work within a very old regulatory framework that needs to evolve,” Fusaro says.

“It’s clear that the old rules aren’t good enough to handle how fast the Internet is changing things,” he continues. “I don’t think anybody can look at you with a straight face and tell you they know how exactly this is going to play out over the longer term.”

Adeniyi Abiodun is a software engineer who’s been in the crypto space for nearly 10 years. Like Geminder and Hejazi, he is a believer in NFTs as a new and intuitive way that content creators can interact with their fans. If a creator has a thousand solid fans, he thinks they “can really keep a living as a creator.”

Creators could end-run publishing companies and other “middlemen” by creating content that is exclusively owned and can be marketed to fans directly.

He finds the possibilities in this new world amazing. Fans or collectors can invest in a work, and “as I grow as an artist, they almost get an equity position in how I do.”

Jaq Chartier is a Seattle-based painter who shows her work at a gallery in San Francisco, as well as other places. She is in her 50s and came up creating tangible works of art. But NFTs caught her attention, and now she has minted one and is putting it up for sale.

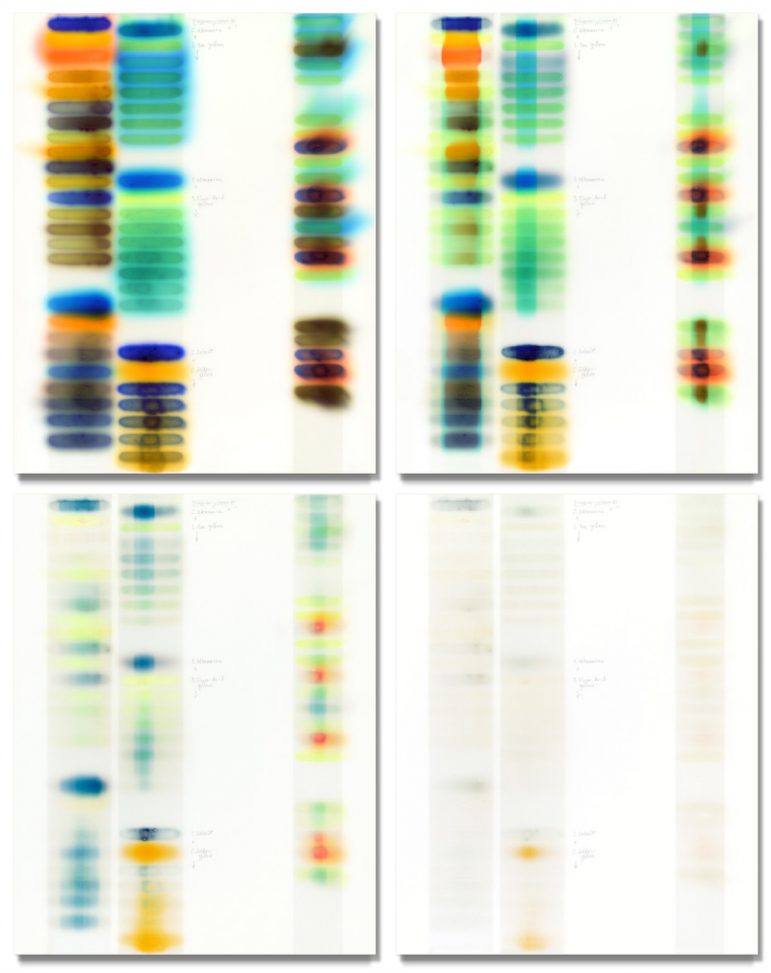

Chartier describes her body of work as “old-school modernist abstract painting,” but she says they “are also experiments.”

Because she often works with materials that are not “orthodox,” she runs tests to measure the fastness of the stain or dye she is working with to see how it fades over time. From the testing, she has accumulated inks and dyes and stains that she doesn’t use in her paintings because they will fade and ultimately disappear.

A few years ago, she began to experiment with documenting the changes in an artwork as the ink faded.

As she worked in the area, Chartier realized that if she periodically scanned an image she could record how it changed over time. And if she strung the scanned images together, she could create a time-lapse of the initial work as it changed.

At first, her idea was to create a video that would illustrate the way that the work changed, and the video could be shown at one of her shows.

Then she heard about NFTs — there was a lot of publicity about artists selling NFTs, particularly after the digital artist Beeple’s $69 million sale of an NFT containing his work — and she wondered if she could mint the time-lapse on blockchain.

She decided to figure out how to do it.

Chartier succeeded in creating a piece called “SunTest #8 (Time-Lapse),” timed to coincide with an exhibition of her tangible art at the Dolby Chadwick Gallery in San Francisco, which runs through May 29.

She plans to sell “SunTest #8 (Time-Lapse)” as an NFT in three editions. As an experiment, when the gallery exhibition opened in early May, Chartier offered the first edition for sale on one of the new platforms that showcase NFTs. There was interest, though it didn’t sell right away.

She isn’t discouraged. The platform wasn’t well-curated (a user could only search for the broad category “art”), and that made it incumbent on her to get the word out. She expects that will change as the market matures.

Chartier thinks of NFT sales as a way to expand the reach of her work. “There’s a younger generation that [doesn’t] even go into galleries,” she says. “They don’t care about the physical object.”

Chartier sees NFTs as a positive thing for “artists who are completely digital and who don’t really have gallery connections. I think it’s an interesting way for them to finally have an audience and be able to get paid something from their work.”

She thinks the “crazy hype” that has followed the multimillion-dollar sales of NFTs will “settle into just being another way of artists making work and getting it out there.”

Cent’s first promise to its community is “You have full control over the monetization and distribution of content you create, social actions you take and relationships you form with people online.”

Geminder says “our whole thing is we’re never going to have ads on Cent.” She says she doesn’t think that selling advertising is inherently bad, but it “makes companies make the wrong decision on behalf of the user.”

She says that with Cent, she has found her mission in life. She has worked at many companies but never thought their missions were hers. “After 20 years, this one feels deeply personal,” she says.

The Renaissance came out of the plague, and out of COVID-19, Geminder thinks that “something is going to rise like a phoenix.” She wants that to be a community of creators who make a creative income, and she intends to make that happen.

“If we get our flywheel going and then other businesses [that] are creators are on our platform and get their own flywheels going, then we can change people’s lives all over the world,” she says.

She knows that it is a massive lift and won’t be done by Cent alone.

“I feel weird saying it, but in the core of my being, I believe it,” Geminder says. “I know it can happen.”